Every day, hundreds of thousands of women worldwide get mammograms, and thousands more are sent by their doctors for biopsies to confirm or rule out the presence of breast cancer — painful, anxiety-filled procedures that don’t always return accurate results.

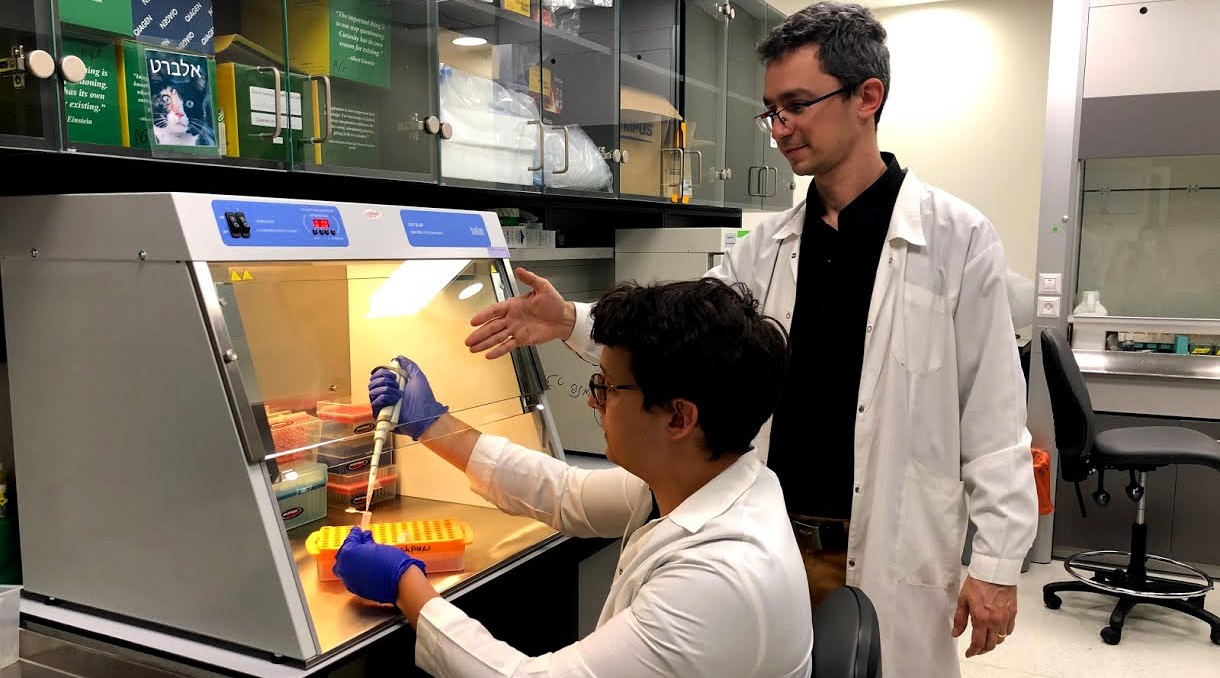

Dr. Albert Grinshpun of Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem wants to change that. His goal: to perfect a universal liquid biopsy approach to early detection of circulating, cell-free DNA in breast cancer patients long before the cancer can spread and threaten their lives. A liquid biopsy examines a body fluid, typically the blood, for evidence of cancer.

“With the standard exam, if you find something suspicious, you send the patient for a biopsy, which means putting a needle into the breast and taking some tissue,” Grinshpun said. “Only 25% or even fewer of those biopsies turn out to be cancerous, which is great for the patient, but what about all the time and effort invested by the medical system?”

Mammograms, generally recommended annually for all women over age 50, also sometimes miss tumors, especially in younger women with dense breast tissue. While doctors sometimes recommend that such women get an MRI, it’s expensive, often isn’t covered by health insurance and like all tests can incorrectly report a positive result.

Women sometimes are subject to multiple biopsies.

“This puts them under terrible stress,” Grinshpun said.

By contrast, liquid biopsies allow researchers to isolate genetic material known as circulating cell-free DNA (or cfDNA), from bodily fluids. Extensively studied by Grinshpun’s mentors at Hadassah and Hebrew University, Yuval Dor and Beatrice Uziely, the procedure detects DNA in the blood from tumor tissue.

“Many people believe liquid biopsy is the future of medicine,” Grinshpun said. “We want to develop a test that will fit all women.”

Grinshpun hopes that accurate liquid biopsies will be the culmination of a new three-year research project he began on Sept. 1. That project is being financed by a $200,000 grant co-funded by the Israel Cancer Research Fund, or ICRF, and Conquer Cancer, an effort of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Conquer Cancer said it was drawn to support Israeli oncology research thanks to the ICRF, which raises millions of dollars annually in North America to support cancer researchers working in Israeli hospitals, universities and other institutions.

“Providing support for projects like this, which focus on the development of technologies to enhance the early detection of life-threatening cancers, resonates with our donors because it holds hope for improved cancer outcomes in the near term,” said Dr. Mark Israel, ICRF’s national executive director.

Circulating cell-free DNA has the potential to be a universal and powerful marker for detecting and monitoring breast cancer, according to Grinshpun.

In a study published earlier this year in Annals of Oncology, Grinshpun and his team examined the cfDNA from the plasma of 34 patients with localized breast cancer before and throughout treatment with chemotherapy. High levels of cfDNA indicate aggressive molecular tumor profiles and high levels of metabolic activity. But he found that during chemo, cfDNA levels fell dramatically, and the presence of breast cfDNA toward the end of chemo treatment reflected the existence of residual disease.

“If you’re able to find and isolate DNA from the tumor, you can get a lot of insights, such as the tumor’s response to therapy, its size and how it developed,” Grinshpun said. “Ideally we will take women who come for biopsies and analyze their blood for cfDNA from the breast. Our goal is not to avoid mammography but to avoid unnecessary biopsies.”

Scientist Sivia Barnoy is working on ways to identify carriers of mutations of the breast cancer BRCA gene by identifying blood relatives of those diagnosed with hereditary conditions and who are at high risk of cancer. (Courtesy of Barnoy)

Genetic testing for families of BRCA carriers

Another pioneering Israeli breast cancer researcher, Sivia Barnoy of Tel Aviv University, is working on ways to identify carriers with mutations of the breast cancer BRCA gene through “cascade screening” — the process of identifying blood relatives of people diagnosed with hereditary conditions and who are at high risk of cancer

Barnoy’s project involves 350 Israeli women of all ages, and is being done in collaboration with similar studies now underway in Switzerland and South Korea.

Under Israeli law, genetic test results belong to that person only. While surveys show that the vast majority of patients would disclose results to family members, often they end up not doing so because they can’t find the right moment or don’t feel comfortable, according to Barnoy. As a result, some women who test positive for a BRCA mutation that causes breast cancer fail to inform at-risk relatives.

“Often they disclose this information just to the immediate family, but not to their cousins,” said Barnoy, a geneticist and associate professor of nursing at Tel Aviv University. “We want to examine the whole family tree. This way we can promote the health of these people, get them to reveal this mutation and have other family members get tested.”

Barnoy’s team is using hospital records from Tel Aviv’s Ichilov and Haifa’s Rambam hospitals to examine patients’ disclosure behavior. The study, being financed by a three-year, $180,000 ICRF grant, is particularly relevant for Israel, given that 2.5% of all Ashkenazi Jews carry a BRCA mutation, compared to less than 0.25% of other populations.

Breast cancer metastasis

Hava Gil-Henn, an assistant professor at Bar-Ilan University, is working on a project to understand the molecular, cellular and whole-organ aspects of breast cancer metastasis — secondary malignant growths found distant from the primary site of the cancer.

“We focus on metastasis because this is what generally kills breast cancer patients,” Gil-Henn said.

Currently there is no inhibitor to arrest metastasis. The goal of Gil-Henn’s project, supported by a three-year, $180,000 grant from ICRF, is to find one and develop better prediction tools.

Similarly, Hebrew University researcher Yoav Shaul is studying whether metabolism plays a role in the ability of cancer cells to become more aggressive and metastasize. Proliferation of cancer cells isn’t the only danger, Shaul said. Over time, cancer cells also can become more resistant to chemotherapy, and they have the ability to migrate and form metastasis. Some cells even within the same tumor can vary in their levels of aggressiveness.

Trying to counter that aggressiveness, Shaul’s lab is using a three-year, $135,000 ICRF grant to study whether it’s possible to “switch off” the specific metabolic enzymes expressed by aggressive cells. That, Shaul hopes, will inhibit the progression of treatable low-grade tumors to more advanced, untreatable stages.

This understanding, Shaul said, eventually “could lead to the development of a new class of anti-cancer drugs that will maintain the cancer cells in their less aggressive form.”

If successful, these researchers’ work could result in significant gains in scientists’ understanding of how cancer cells behave — and how to more effectively treat them.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Israel Cancer Research Fund, whose ongoing support of these and other Israeli scientists’ work goes a long way toward ensuring that their efforts will have important and lasting impact in the global fight against cancer. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.

More from Israel Cancer Research Fund