(JTA) — Before I met him, I saw Benjamin McDowell’s name in the news. Inspired by Dylann Roof, the notorious shooter responsible for the Charleston church massacre, he planned an attack on a synagogue that was thwarted by FBI agents.

No lives were lost. No lasting physical harm was done, though the synagogue members certainly felt threatened and terrified. I read the news item online and, though I didn’t yet know the word, doomscrolled onward.

I probably wouldn’t have thought much about McDowell again had I not seen a video of him in my Facebook feed three years later. Rabba Karpov, the rabbi of Jewish Center of Indian Country, Oklahoma, had posted a Youtube video uploaded by McDowell in which he expressed remorse for his past behavior. (The video has since been removed, though I don’t know why or by whom).

I watched the video and was genuinely moved. Something had happened to Benji while in prison. Here he was, talking about the power of love and light to transcend differences, political and religious, and how we were all part of one larger human family. How many of us have undergone such a profound, public transformation from deadly darkness to hope? How many ex-White Supremacists are out there seeking to amend their past ways?

A few nights before I had watched the film “Burden,” which tells the true story of how a Black minister, Reverend Kennedy, welcomed a former KKK member, Mike Burden, into his home and changed his life forever. Inspired by this radical act of loving kindness on the reverend’s part, I felt compelled to act on the video of McDowell. I reached out to him directly on Facebook.

Even though I have invited anti-Semites into my home before, I generally believe it is not the Jewish people’s responsibility to combat anti-Semitism — in the same way that it is not Black people’s responsibility to dismantle systemic racism. Racism, sexism, anti-Semitism and xenophobia are prejudices which plague society, and we as a nation bear a communal responsibility towards eradicating them.

But a communal responsibility is fulfilled through countless individual acts. And I knew that encounters with people from such a polar opposite outlook can be sacred and potentially profoundly impactful.

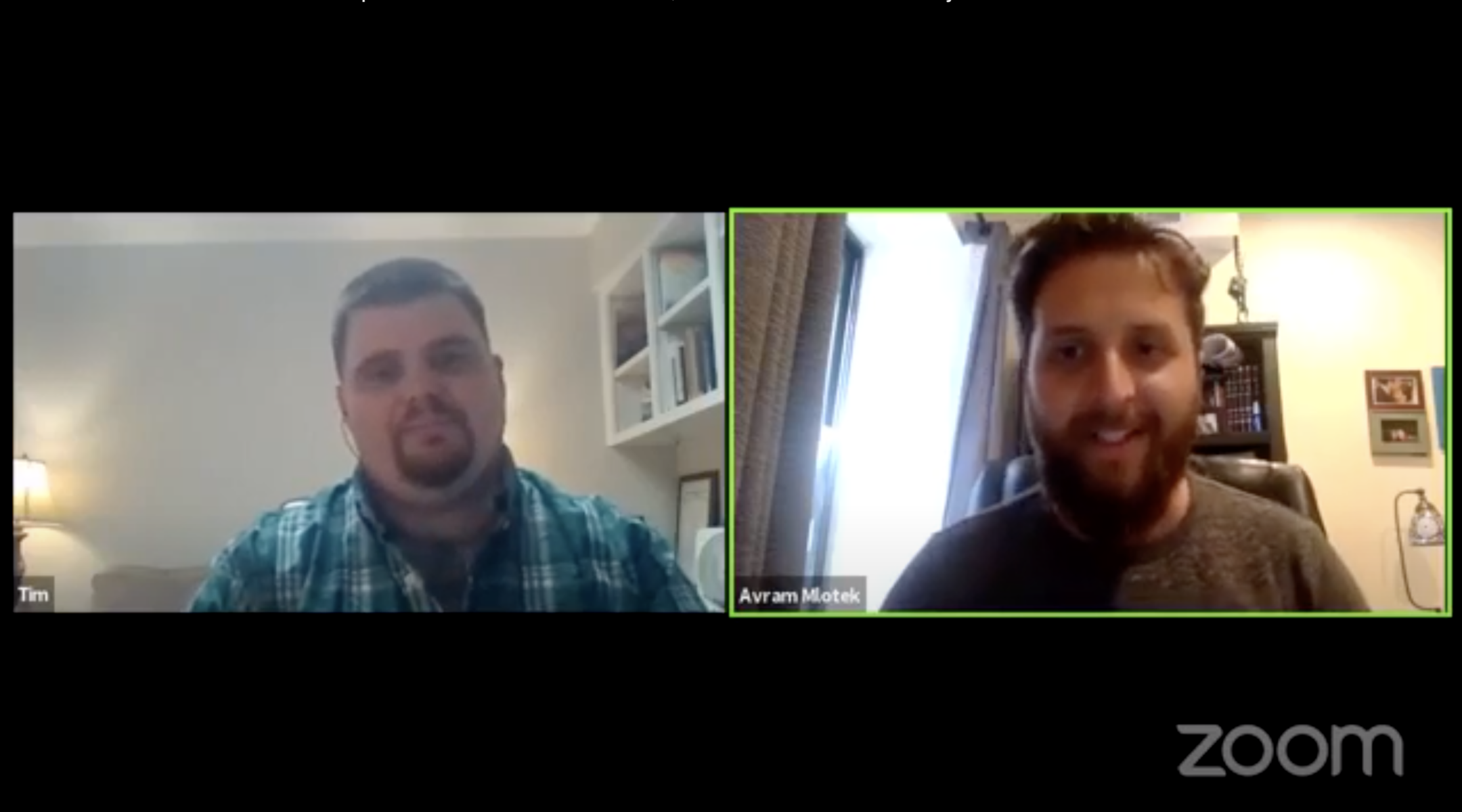

After some texting and a phone call, I invited Benji onto my show, “A Rabbi And A —– Walk Into A Zoom.” I’ve hosted priests, Holocaust survivors, doctors, musicians, actors — even President and Michelle Obama’s speechwriter — but never before a repentant white supremacist. And so, we had our event’s name: “A Rabbi And A Former White Supremacist Walk Into A Zoom.”

He described meeting with an undercover FBI agent who was ready to sell him weapons to use against the Jewish community. The FBI had tracked his hateful rhetoric online and sought to see just how close this one blogger was to bringing his online musings into fruition.

What struck me most during our conversation — which took place on Sept. 14, right before Rosh Hashanah — was the dissonance McDowell described between his online and real-life experiences. Online, he was being inculcated with and reflecting back an ideology centered on the idea that Black people and Jews are destroying society. But he said that even when he was writing hateful messages about Black people online, he always treated them fairly when he countered them in real life.

“And Jews?” I asked.

He had never met a Jew before. Our conversation, he said, was the first time he had knowingly spoken to a Jew.

The Rabbis of the Talmud wrote of the spiritual potency of teshuvah, a genuine return to one’s self, heartfelt repentance. They wrote that teshuvah has the power to transform one’s intentional sins into meritorious deeds. A preposterous sentiment! However, when speaking with Benji, I saw how teshuvah indeed could be seen this way.

His intentional hateful acts had brought him to this meritorious place of seeking out reconciliation.

Though our country is engulfed in national turmoil, and we are each convinced of our own political righteousness, McDowell said he was undergoing a personal transformation. (He told me he doesn’t follow the news much because its toxic nature isn’t the most conducive to his emotional recovery, as he puts it.)

How many of us have given up on Fox News viewers, or MSNBC viewers, because they are dead set in their ways? How many of us refuse to engage with someone who says “All Lives Matter” or “Black Lives Matter” because we are so disgusted by the sentiments we think are motivating them? If Benji has taught me anything, it is to never believe the lie that we are conditioned to believe: that people cannot change. People can.

It is ironic that I encountered Benji through Facebook, a social media giant which is often under criticism for fueling misinformation and polarization. I myself experienced Facebook’s mishandling of hate speech when its moderators removed a post I wrote about being assaulted by Farrakhan supporters on a subway car.

The platform, for all of its flaws, permitted Benji and me to connect. But as Benji himself puts it, it was also the echo chamber of the online groups he had found, which further fueled his toxic thinking. If Facebook chose to actively combat misinformation and hate speech, who knows how many Benjis would be steered away from falsehoods? Facebook’s new policy banning Holocaust denial on its platform is a welcome change that comes several years too late.

In the age of COVID-19, we are online now more than ever. For me, Benji’s story is serving as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of echo-chambers, a reminder to Facebook of the heavy burden they now carry as a connector of people.

But may we also remember that there are people behind the profiles. Real human beings with emotional range and capacity. Let us never lose sight of each other’s humanity, no matter how deeply we doomscroll.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.