This post originally appeared in Alma.

I had never heard the word “Bukharian” until a few years ago. It was said in relation to food — as most things surrounding my Jewish identity seem to be. The food in question was dushpara, a dumpling dish that my savta would only make on special occasions.

Whenever I would eat dushpara, I remember bragging about it to my Jewish friends. I would tell them about how many hours my savta spent folding the dumplings, simmering the meat, spooning the broth and how close I was to being able to make it myself. I figured they also ate dushpara — we all went to Hebrew school and services, so it only made sense that we would share this, too.

But they never knew what I was talking about, and I would be confused. Don’t all Jewish grandmas make dushpara?

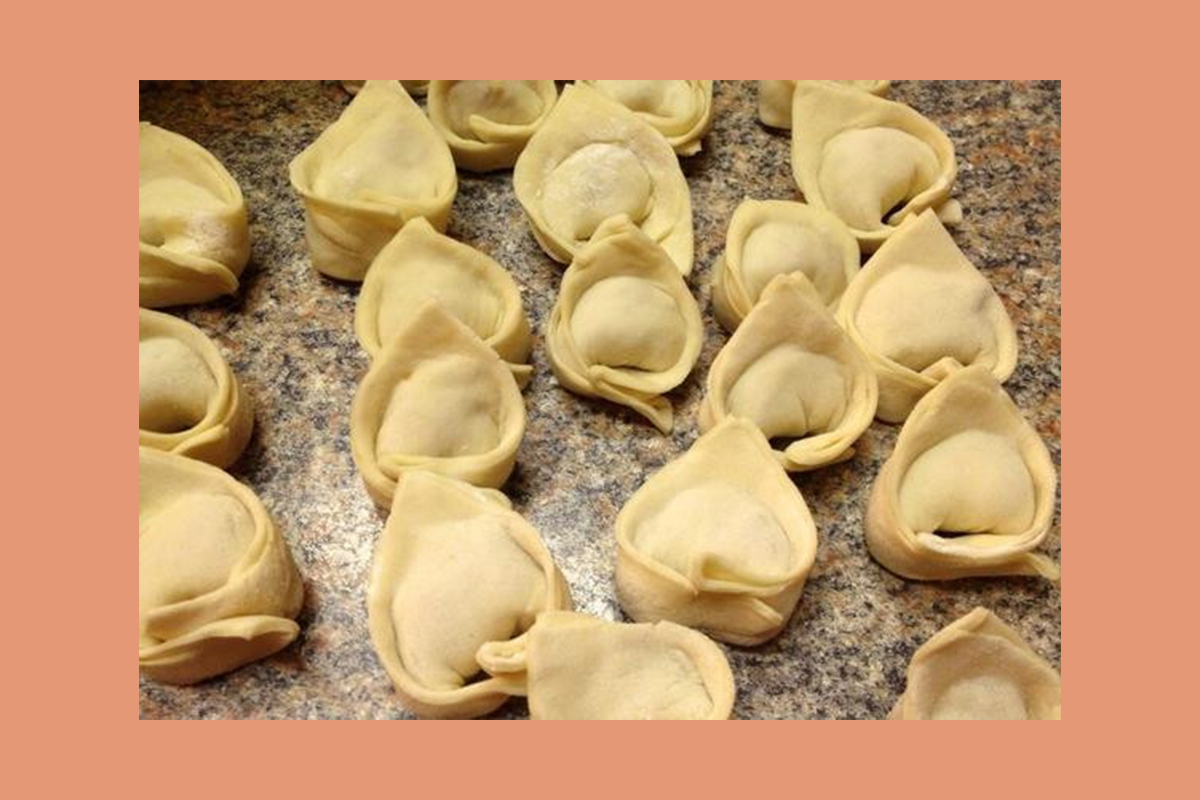

Duspara before boiling. (Wikimedia Commons)

It wasn’t until high school that my savta told me that dushpara came from our Bukharian culture, an aspect of my Jewish identity that I shared with none of my friends. Dushpara, which was once an unfamiliar word, became well-worn after years of asking for it, rolling it around my tongue, feeling its creases. Bukharian, on the other hand, was still unknown. It left a metallic trail in my mouth. It didn’t belong.

Ever since I was a baby, I have known Judaism. My parents made an effort for me to not just be Jewish, but to feel, deep in my bones, the Jewish tradition. Or, a Jewish tradition. I chanted Torah, said the prayers, sang the songs, learned the stories. And I felt Jewish. When I grew older, I started asking questions and became dissatisfied with the answers my synagogue provided. I began expressing my Judaism through my actions, my organizing, my activism — and I felt more Jewish than ever before.

But when my savta said this word, told me that I was Bukharian, told me about an identity I never knew I had, I didn’t feel Jewish anymore. Rather, I didn’t feel like the kind of Jewish that I thought I had been my entire life — Judaism with a certain history and certain traditions and certain music and certain prayers. Suddenly, that Judaism, like the word Bukharian, felt foreign. And, suddenly, I felt foreign as well.

Bukharian Jews are Jewish people who came from Bukhara, a region now within modern-day Uzbekistan. There’s not that many of us left, and of the maybe 70,000 who are in the United States, 50,000 reside in Queens, New York, perhaps the only thriving Bukharian community on the continent. Bukharian Judaism has its own dialect, its own culture, its own clothing, its own cantillations, its own music, its own food. Its own identity.

But it was never mine. When my grandparents immigrated to the United States, they stopped speaking Bukhori, a Bukharian dialect. They stopped wearing the clothing, singing the prayers, chanting the cantillations. They continued to cook some of the dishes, but that was about it. Growing up, my dad knew around as much about his Bukharian background as I did.

My last name, Hahamy, is a relic of my relation to Rabbi Shimon Hakham, a Bukharian Rabbi who translated Hebrew books, including the Torah, into Bukhori. Many of these translations are still used today. For his efforts, a portrait of him can be found in a cramped room atop the Bukharian Jewish Community Center in Queens. It’s this last name that I hold as a testament of my lineage. A link proving that, even though I don’t always feel it, I am a Bukharian Jew. Sometimes I believe that, if I say my last name enough, I might make up for years of no connection.

Rabbi Shimon Hakham circa 1910. (Wikimedia Commons)

I don’t live in Queens, and I’ve never been. But I know that I have generations of family there: Bukharian Jews who speak in Bukhori, wear traditional clothing, sing traditional cantillations, belt boisterous melodies, cook dushpara and so much more. Bukharian Jews who carry their traditions to this day, and are so proud.

I’m more than thankful for that initial conversation with my savta, which opened me up to a new and rich and exciting world. But I’m also angry that it took so long, and that, even now, I’m hesitant to claim the identity as my own.

American Judaism is dominated by Ashkenazi Jewry and its subsequent practices, and the impacts of Ashkenormativity are far-reaching beyond my own experience.

But my experience, in and of itself, is quite devastating. I’ve grown up practicing only Ashkenazi Judaism, and believing that that was the only type of Judaism that was valid. I never learned Bukhori or Ladino from my grandparents, because I was never taught that any dialects beyond Yiddish existed.

I still struggle with feeling as though the Sephardi and Bukharian practices that I’m now trying to learn are, in a way, inferior because they aren’t Ashkenazi. I can’t help but feel that I’ve lost so much time, so much knowledge, and so much pride.

I want to be able to sing and dance and speak in the way that my ancestors used to — and not to feel less Jewish for doing so. I want to be able to say the word Bukharian and for it to not feel foreign and metallic, but warm. I want it to readily roll off my tongue as though I was born with the word fully formed on my lips. I am a Bukharian Jew. I am a Bukharian Jew. I am I am I am I am I am. I am.

I’m working on it. And one day, I’ll get there. I’ll be so proud. As I should be.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.