(New York Jewish Week) — Zvi Luria can sense a road’s temperament. A retired senior engineer, he planned highways, bridges, interchanges and tunnels for the Israel Roads Authority and, as he says, he has hundreds of kilometers in his soul.

In his latest novel, the distinguished Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua describes how Luria, at the edge of dementia, is pulled back into his profession, to help build a secret military road in the desert, a thruway with particular twists. “The Tunnel” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), beautifully translated by Stuart Schoffman, is also a love story, an urgent story about the State of Israel, layered with insight about history, memory, human nature. The appearance of a germ “both virulent and sly” is one of many elements that makes this a novel of the moment.

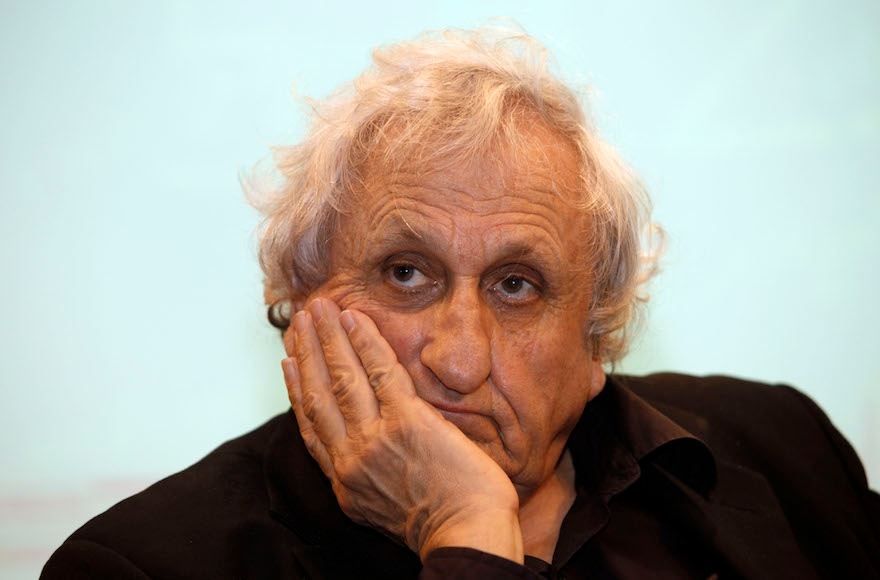

Yehoshua, one of Israel’s greatest novelists, has written 11 previous novels, including “Mr. Mani” and “A Journey to the End of the Millennium” and has won numerous awards including the Israel Prize, two National Jewish Book Awards and France’s Prix Medicis Etranger. His works have been translated into 28 languages and adapted for film and opera.

“Every book I do is different,” Yehoshua says in a zoom interview from his home in Givatayim, Israel, along with Schoffman, from Jerusalem. A conversation shifted naturally between the novel and Israel’s past and future.

I liked this book so much that I read it a second time soon after finishing it, to savor the language, the very likeable characters, the episodes very Israeli and universal. Film rights have already been sold, but held up by Covid.

Schoffman, who grew up in Brooklyn and has lived in Jerusalem since 1988, explains that the novel “interweaves dreamlike passages, with an underlying realism; they coexist in a way that makes this an extremely rewarding novel. A challenge in translating is to make sure that the simultaneity of dream and reality comes off as seamless and persuasive as possible.”

Yehoshua was inspired to write this by a close friend, a fellow writer, who began suffering from dementia. His friend faced the situation with humor, and that gave Yehoshua the possibility of adding humor and spirit to what might be a dark and depressing subject.

Luria is almost 73, and has been married to Dina, a pediatrician with a senior position at a major Tel Aviv hospital, for 48 years. One of the first signs of his dementia is that he is forgetting the first names of people he knows, as though there is a black hole swallowing them up, even as he remembers other details. When a kippah-wearing neurologist finds a slight atrophy on his brain, Dina follows his suggestion of keeping Luria engaged in life and encourages a young engineer, Asael Maimoni, to take him on as an unpaid assistant.

Soon after, Luria and Maimoni are headed to the Ramon Crater in the Negev. At one point, they get out of their government vehicle, and Maimoni loses sight of Luria – as he had promised Dina he would never do — when he climbs up on an overpass without a railing. Fearing the worst, Maimoni soon finds his assistant sipping coffee in the shade of a eucalyptus tree, gathering with a group of Jewish and Arab workers and project managers, including one he trained.

The plot unfolds, as the secret road isn’t much of a secret, but few know that the project may require a tunnel built through a hilltop, to protect ancient Nabatean ruins and a Palestinian family hiding there.

Detours in the narrative include an unusual shiva, hospital adventures, family matters and more episodic road trips. In fact, Luria’s hint of dementia allows him a certain freedom and, in spite of the forgetfulness, a sense of clarity.

“Enduring Chemistry”

The marriage of Dina and Zvi is playful, with tender understanding. Maimoni immediately notices their “enduring chemistry” and looks at them with awe.

“I as a writer took upon myself a mission, to repair the damage that other writers are doing to married life, all the time,” Yehoshua says.

His own wife, to whom the book is dedicated, died after a short illness when he was in the middle of writing this novel. He was distraught, but found the courage to continue and finish. His late wife was a psychoanalyst and he says he learned from her “24 hours a day.” He points to his heart, “Know yourself.”

The novel’s setting, much of it in the desert, with its ancient landscape, is significant to Yehoshua. “Jews in the diaspora and other people don’t know that half of Israel is desert. In the desert is the challenge of the future of Israel,” he says. He’d rather see settlements in the desert than the West Bank, and there is open space for more newcomers.

His own vision, after many years of supporting a two-state solution, is of a binational state. “The problem is how to find with the Palestinians on the West Bank a modus vivendi to live together, a kind of coexistence without apartheid.”

I as a writer took upon myself a mission, to repair the damage that other writers are doing to married life, all the time.

Always, he encourages Americans to move to Israel. “Help us keep the majority,” he says.

Born in Jerusalem, Yehoshua, who has been known since childhood as Bulli, lived for many years in Haifa, where he taught literature at Haifa University. He sees Haifa as a “model of a city.”

“I always pray that Israel will be like Haifa, where there’s a harmonious balance between Arabs and Jews, between religious and secular Jews, between the many people who live there.”

Schoffman points out that hospitals, like the one in the novel, “are the great levelers, where the ethnicity of patients and medical staff isn’t relevant.” Dina treats Israeli Jewish children of all backgrounds as well as Palestinians, both Israeli citizens and West Bank and Gaza residents, including children brought to the hospital by volunteers for Road to Recovery. It’s an actual group, whose Israeli members transport Palestinians to hospitals inside of Israel for chemotherapy, dialysis or other urgent care.

Names are important in this novel, as in other works by Yehoshua. Some names have biblical resonance; others hint at figures of Jewish history and thought. An inscrutable character named Shibbolet, supervisor of the Nature and Parks Authority in the Negev, has first and last names merged into one that suggests many meanings. Some links are coincidental: Yehoshua says that he learned after the novel was completed that Zvi Luria was the name one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. And, names are forgotten.

Professions are also key for Yehoshua. The engineers plan roads and tunnels that connect one place with another, making access possible, spreading light at the end of the tunnel. In previous novels, he has written about an elevator engineer, a garage owner, a young surgeon and others, and depicts their workplaces. For Yehoshua, a profession is “an indication of character, vision, ambition. I want to know who this person is.”

We have to revitalize the solidarity that we lost, tunnels have to be created, dug between different sectors of Israeli society, with the religious, with Arabs.

The novel’s final scene, powerful and enigmatic, evokes William Faulkner, a writer Yehoshua admires, in particular a story called “The Old People.” (Writing in The New York Times Book Review, Harold Bloom described Yehoshua as an Israeli Faulkner.) No spoilers here. But Schoffman points out that the name of the chapter, “Land of the Hart,” refers to the name Zvi, which means deer, and hart is a male deer. The chapter in Hebrew is called “Eretz Ha Tsvi,” a biblical name for the Land of Israel, and also the title of a 1974 book that appeared in English translation as “Land of the Hart.” Its author, the Israeli politician Lova Eliav, a close friend of Yehoshua’s, envisioned an Israel of peace and coexistence, a country with a big heart.

“I am almost 84, born in ’36, before the State was born,” Yehoshua says. “I passed through many difficult moments, was in the Army, etcetera, and one of the great secret powers of Israel was solidarity. Now, we have to revitalize the solidarity that we lost, tunnels have to be created, dug between different sectors of Israeli society, with the religious, with Arabs. Without solidarity, we will not be able to win this battle against the corona.”

Luria sounds like Yehoshua when asked by a harpist, the mother of his grandson’s friend: “Do you really believe in this country?” He responds, “Do I have a choice?”

Join the Jewish Week and UJA-Federation of New York on Oct. 13, 12:30 pm for a conversation with A.B. Yehoshua, one of Israel’s finest novelists, and Stuart Schoffman, the translator of Yehoshua’s new novel, “The Tunnel.” Moderated by Sandee Brawarsky, culture editor of The Jewish Week. Free to UJA donors, $18 for new donors. Register here.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.