MONACO (JTA) — This tiny wealthy country on France’s southeastern coast is famous for its beautiful beaches, coastal mansions and splendid casinos.

Outside of Israel, Monaco also has the highest ratio of Jewish inhabitants of any country in the world, at over 5%, according to statistics provided by its two rabbis.

To be fair, the city-state’s total population is only about 38,600, making it one of the world’s smallest nations. But its some 2,000 Jews are cultivating a growing community thanks in part to a luxurious synagogue opened in 2017.

Synagogue Edmond Safra, which was buoyed by a donation of more than $10 million by the Safra banking family, is housed inside a building that is shaped like a Torah scroll, its cylinder featuring Jerusalem stone tiling. The structure is oriented to see the Mediterranean and the famed Monaco marina — but has no windows to view them.

The Safra congregation isn’t new, but Daniel Torgmant, its rabbi since 2010, says the new building “has quite simply been an engine for communal growth.” Because of its attractiveness and prime location, “it allows us to attract a lot of people passing through Monaco, or Jewish people whose connection to Judaism is still in its infancy.”

Designed to resemble the far larger Edmond J. Safra Synagogue in Manhattan, the Monaco version has a flat roof that boxes in and conceals a domed ceiling with wooden panels that is revealed only in the interior to dazzling effect. The interior’s artificial lighting is so ample that it sustains blooming orchids in pots affixed to wood-paneled circular walls. Several wooden circles, each one larger than the previous, surround the rabbi’s pulpit. They ripple outward in the direction of the pews, which have about 400 semicircular seats upholstered in purple velvet.

“Having facilities like this really helps bring people in,” Torgmant said.

A view of Monaco’s Port Hercule in 2017 (John Greim/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Like the vast majority of the population here, most of the principality’s Jews were born abroad. Many are millionaires who have come to the tax haven country, where earnings require neither reporting nor sharing with the government. Others are middle-class employees in the tourism, gambling and banking sectors.

The resulting Jewish population is a relatively new and diverse community whose members speak different languages and come from disparate cultural backgrounds.

There is a bit of religious diversity as well, even though both of the state’s synagogues — Safra and a Chabad-Lubavitch movement outpost — are technically Orthodox. Each has members who are not very strictly Orthodox in their own homes, including many Russian-speaking Jews who own businesses, Israeli entrepreneurs, and French- and English-speaking Jews with ties to the banking sector.

The Chabad synagogue’s appearance pales in comparison to Safra. Situated on the ground floor of a residential building, its prayer hall can hold about 80 people and lacks the stylish kind of furniture on display at Safra.

“The Jews who live here don’t come to us for material reasons, they tend to be well-off,” Tanhoum Matusof, the Chabad emissary who runs the Jewish Cultural Center of Monaco with his wife, Chani, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. He recalled one congregant who wondered why the synagogue needed a mikvah, a ritual bath, seeing as so many of its congregants have their own pools.

“They need us for spirituality and a sense of community, which is something you don’t need a beautiful building to give.”

Still, the Matusofs do take into account the standard of living to which many Jews in Monaco have become accustomed. Their mikvah, for example, resembles a prestigious spa, and holiday celebrations are sometimes held at one of the city’s ritzy hotels rather than the synagogue.

“Listen, one has to understand one’s audience,” Matusof said.

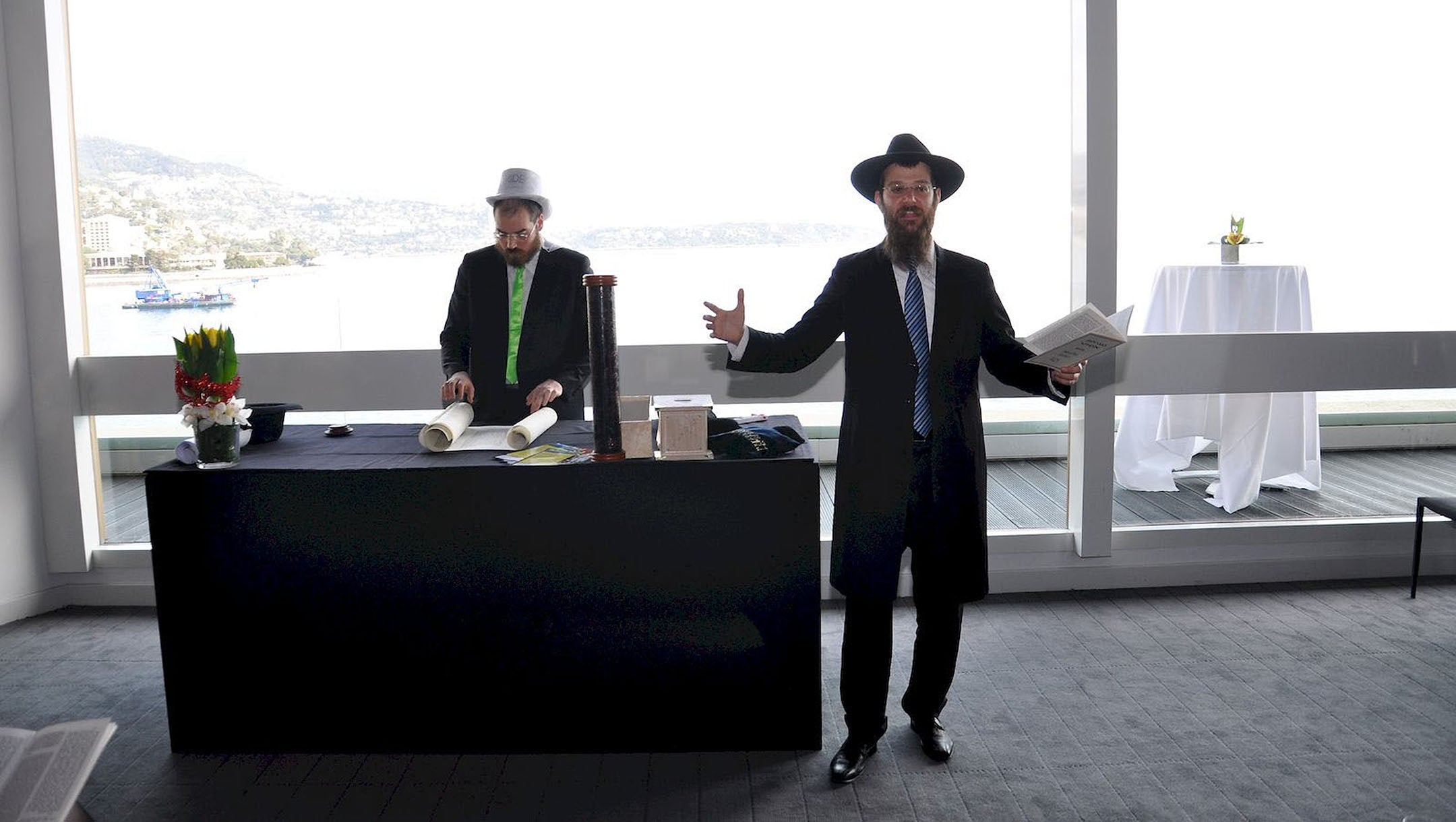

Rabbi Tanhoum Matusof reads from the Book of Esther on Purim in Monaco, Feb. 28, 2018. (Courtesy of the Jewish Cultural Center of Monaco)

At Matusof’s synagogue, which has about 200 regular congregants, services are held in English for the convenience of the many congregants who don’t speak French. English is also sometimes used at the Safra synagogue, but French is more dominant there.

The relative simplicity of Matusof’s synagogue also has its charms for some of Monaco’s middle-class Jews, like the family of Mahnaz Grosjen, an Iran-born mother of two. She and her family moved from Geneva, Switzerland, to Monaco seven years ago at the request of her husband’s employer.

“I was actually not looking forward to raising teenage kids in a very materialistic place,” said Mahnaz, who works as a fashion designer. “We’re not from the jet set. I actually like that our synagogue looks like any other normal synagogue in Paris or London. I think it sends the right message.”

But even some of Monaco’s Jewish millionaires also feel more at home at Matusof’s synagogue, which they say has a younger and more international congregation.

“It’s a small, humble place but it’s warm and vibrant,” said Aaron Frenkel, the Israel-born owner of the Loyd’s Group of real estate and aerospace industries, who has lived many years in Monaco with his Croatia-born wife and their five children. He is also the president of the Limmud FSU Jewish organization.

“Maybe it reminds me of Bnei Brak,” he said, referencing the religious Israeli city where he grew up that is home to hundreds of small synagogues. “Whatever the reason, my synagogue here feels like home.”

The core of Torgmant’s congregation, the rabbi says, is Sephardic Jews older than 60, though the new building has helped bring young families into the fold. Visits to the Safra synagogue have quadrupled since the building’s renovation, and the number of bar mitzvahs and ritual circumcisions have increased dramatically, to about 50 a year, Torgmant said.

A man walks outside the Synagogue Edmond Safra in Monaco, March 7, 2018. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

Before the coronavirus shut down international tourism, the Safra synagogue’s opening led to an increase in the number of Jews who came there for Shabbat services from cruise ships. They typically dock at the glitzy marina, which is surrounded by cafes and restaurants (it also boasts an open-air skating rink that remains open well into April).

“It really made things much more dynamic here. It’s like a beacon of light that brings Jews here,” Torgmant said.

One of the families drawn to the light are Borya and Masha Maisuraje, Russian Jews who are originally from the Republic of Georgia and own a shipping company in Kaliningrad, Russia. They moved to Monaco in 2009 but “had very little to do with Judaism” before the opening of the new synagogue in 2017, Borya said. That year, they decided to plan a bar mitzvah for their youngest son, Alexei.

“It’s welcoming here, it’s a place you immediately feel comfortable in,” Borya Maisuraje said. “We suggested it to Alexei and he immediately said yes.”

Monaco does not have a Jewish school, though both synagogues provide Sunday and Hebrew schools, as well as youth activities during vacations. More observant parents send their children to one of the Jewish schools in Nice, a French city about 10 miles away and also the source for Monaco’s fresh kosher food.

Unlike Nice, where many Jews feel unsafe, walking around with a kippah is no problem in Monaco — anti-Semitic incidents are extremely rare and police have a robust presence. There is about one officer per 70 residents, more than four times the European Union average.

A parliamentary principality with its own royal house, Monaco has a land area that’s smaller than Central Park and is the world’s most densely populated country, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division.

Jews pray at the Jewish Cultural Center of Monaco in 2018. (Courtesy of Rabbi Tanhoum Matusof)

Millionaires constitute a third of the population — a ratio higher than anywhere in the world, according to the 2019 Knight Frank Wealth Report. The annual GDP per capita in Monaco was $185,000 in 2018, more than three times the figure for the United States.

The Safra and Chabad synagogues each have a mikvah and a large garden. The latter amenity allowed them to host outdoor services throughout the High Holidays, despite local measures that either severely limited or banned gatherings in closed spaces to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

Matusof says Monaco’s mild Mediterranean weather allows the community to comfortably spend hours on end in the sukkah, or ritual hut that Jews build for the Sukkot holiday.

“We always enjoyed having a yard because it means our synagogue has its own sukkah on Sukkot,” the rabbi said. “We just never thought our sukkah would end up being our synagogue.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.