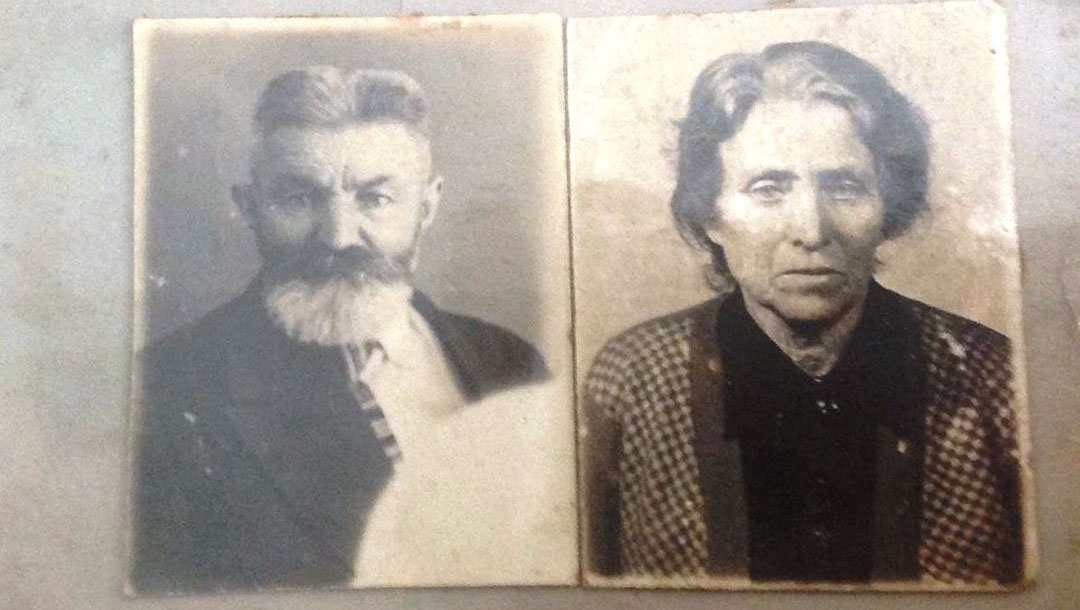

(JTA) — For most of his life, all the information Igor Kulakov had about his paternal great-grandparents was their picture, their names and the fact that they had been murdered during the Holocaust.

The assumption in his family had always been that Sheindle and Mordechai Sova were shot at Babyn Yar (often spelled “Babi Yar”), a ravine on Kyiv’s outskirts where German troops massacred at least 33,000 Jews in September 1941, in one of the largest massacres of the Holocaust.

But beyond that, he was unable to unearth any further details, even after attempting to research the subject in the Kyiv city archives. As he grew older, the uncertainty began to have a psychological effect on him.

“I would get physically ill whenever I needed to pass near Babyn Yar,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

But in recent months, Kulakov, a 45-year-old linguist who lives near Kyiv with his wife and three children, has been able to fill in many of the blanks thanks to a new research project led by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, an organization established in 2016 to build a Holocaust museum in Kyiv. The center’s Names project — which began last year and has led to the identification of 800 Babyn Yar victims whose fates had been previously unknown — provided Kulakov with the couple’s former address, age, place of burial, as well as the terrible specifics of their final hours.

Stray dogs roam the Babyn Yar monument on March 14, 2016 in Kyiv, where Nazis and local collaborators murdered 30,000 Jews in 1941. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

The lack of such identifying details is not unusual for Holocaust victims from present-day Ukraine, where some 1.5 million Jews were killed by firing squad between 1941 and 1943, often with minimal paperwork. Ukraine’s so-called “Holocaust by bullets” happened more sporadically, rapidly and chaotically than in the death camps. There is so little information on what happened at Babyn Yar that the total death toll – including Jews, psychiatric patients, prisoners of war, suspected Ukrainian nationalists and communists – ranges between 70,000 and 100,000 victims.

The Names project has so far collected data on about 18,000 people who were killed at Babyn Yar. Of those, only a few thousand have comprehensive person files. Information on many of the others is patchy, sometimes limited to nothing more than their names, according to Alexander Belikov, a senior researcher at the center.

The paucity owes to a mix of factors, including the lack of German documentation, massive wartime damage to Kyiv’s archives, decades of obfuscation when Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, and an outdated archiving methodology that downplayed the importance of individual stories.

“In the Soviet period, and also sometimes after that, the historical methodology in Ukraine placed very little emphasis on individuals, despite the early efforts of some researchers to give victims a face,” said Belikov.

When Kulakov consulted archives for traces of his great-grandparents, all he found was a Soviet-era registry of civilian war casualties that listed their last name, last known address, year of birth and two serial numbers: 1868 and 1869.

“It didn’t even have their first names,” he recalled.

Igor Kulakov learned of the exact fate of his paternal great-grandparents thanks to the Names Project of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center. (Courtesy of Kulakov)

Thanks to the project, Kulakov learned that his great-grandparents were wholesale food merchants, traveling often to arrange shipments from the countryside to the city. On one such trip, during the Holodomor famine of 1932, they took in a starving girl whose mother could no longer support her.

The research also helped ascertain that Mordechai and Sheindle didn’t die at Babyn Yar after all. They had disobeyed the order to report for deportation, which in reality was a call for Jews to be rounded up for murder. They were betrayed to police in October 1941 and executed on the spot, but not before the woman whose daughter they saved convinced them to part with their own daughter Freuda, Kulakov’s grandmother. Their burial place is on Nyzhnii Val Street in Podil, a neighborhood in the center of Kyiv not far from their last known address.

Researchers were able to pull together this story by following leads to locate information in physical archives across Ukraine. They also use various search algorithms to mine digitized archives. Some of the information about Mordechai and Sheindle came from a tip that led to archives in the Ukrainian city of Fastiv, which turned out to be where the Sovas bought their products.

“We’ll interview relatives to get leads, and then cross reference that with relevant archives,” Beilokov said.

Other victims whom the project lifted out of anonymity include Aba Yakovlevich and Clara Abramovna Kaganovich, a Jewish couple who were 48 when they were murdered at Babyn Yar. In the weeks following the Nazi invasion, they used their connections – Aba was a prominent jurist – to get their only daughter and her newly married husband a spot aboard a train headed for Russia.

Having achieved that, they made no further attempts to escape themselves, their file states. The project team obtained a copy of testimony by the concierge at the couple’s building, who said that after the deportation order came, he “helped them aboard” a horse-drawn carriage bound for Babyn Yar.

Researchers hope to eventually have a web page for each identified victim, complete with their life story and picture. Kulakov concedes that learning the specifics of Mordechai and Sheindle’s last days is gruesome and that he still avoids Babyn Yar even now.

“But it’s better to know — much better,” he said. “Only when you know do you have any hope of moving forward. That’s true for an individual person, and it’s true for a nation as a whole.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.