(JTA) — As night falls on the second night of Rosh Hashanah this year, Rabbi Adam Zagoria-Moffet and two shofar blowers will ascend the 144-foot tower of St. Albans Cathedral, the 11th-century church that dominates the skyline of this city of the same name 20 miles northwest of London.

As members of Zagoria-Moffet’s 200-family synagogue assemble — at a safe distance — in the large grassy area below, the blowers will sound the ram’s horn meant to rouse people to repentance at the Jewish New Year.

“Catastrophe is absolutely the mother of creativity in Jewish life,” said Zagoria-Moffet, a Phoenix native who has led the St. Albans Masorti Synagogue for three years.

“People’s hopes and dreams have changed. Their assumptions about their lives have changed. And religion has to respond to that and not just sell a nostalgia for the near past.”

By all indications, the tiny British Masorti movement — the equivalent of American Conservative Judaism — is taking Zagoria-Moffett’s advice.

In the run-up to two of the most important dates on the Jewish calendar, the movement is in the midst of a broad effort to reimagine what the High Holiday experience can be. Members are being encouraged to make their own shofar and learn to blow it themselves, to conduct long contemplative nature walks on Yom Kippur and to generally take ownership of their own High Holiday experience.

“I think it’s going to build greater Jewish literacy in some perverse way, and that is kind of an exciting thing,” said Rabbi Zahavit Shalev, one of the rabbis of the New North London Synagogue, the largest Masorti congregation in the country. “I kind of feel positive about the empowerment.”

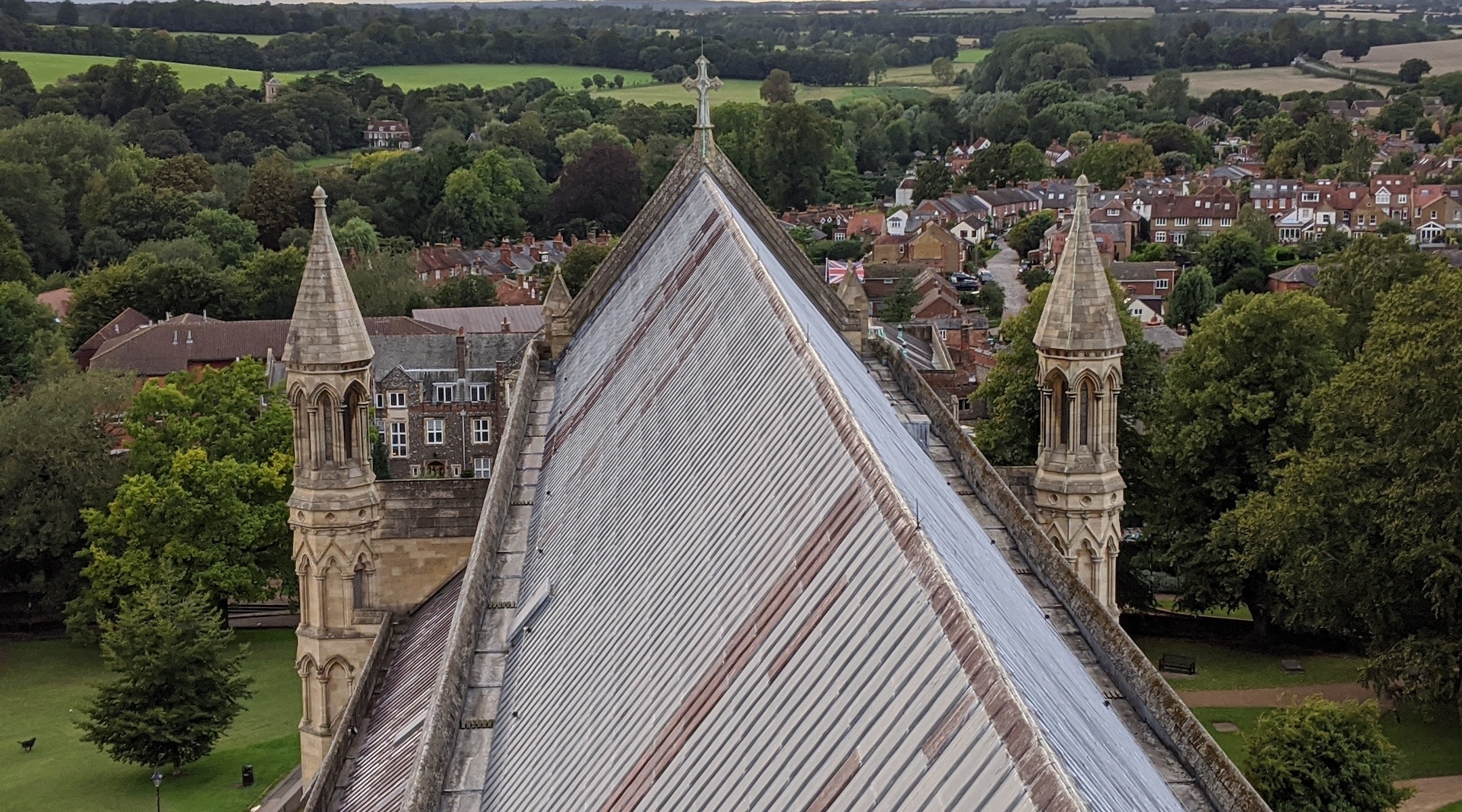

The view from the top of the bell tower at St. Albans Cathedral. (Adam Zagoria-Moffet)

The effort is driven in large part by the British rejection of a decision by the American movement’s religious law authorities earlier this year to permit the livestreaming of synagogue services on Shabbat and Jewish holidays. That decision, widely seen as a rubber stamp on a practice already adopted by many American Conservative synagogues, paved the way for the widespread embrace of livestreamed High Holiday services.

While the decision was greeted with a shrug in the United States, in England it upset a delicate balance within a movement that has long walked a fine line between its progressive impulses and its quest for legitimacy in the eyes of the Orthodox mainstream. Masorti rabbis largely opposed the change, which they saw as undermining traditional Shabbat observance and straying too far from the strictures of Jewish law.

But some lay leaders felt that the streaming of services was integral to maintaining community in an unprecedented moment and felt newly empowered to push for it.

“It basically created a new reality where if there were members who were looking for that to happen, or if there were more liberal parts of the community who were interested in that happening but the leadership was not considering it, it suddenly changed the dynamics,” said Rabbi Chaim Weiner, the director of Masorti Europe and the head of the movement’s European rabbinical court.

Seeking to forge a new consensus, Masorti rabbis put out a statement of their own in June that permitted “passive streaming” in a manner that requires no human intervention. They explicitly rejected the use of Zoom and other interactive platforms that provide for “active streaming” as violations of Jewish law. The passive setup will be prepared before the holiday and be a one-way stream — meaning congregants will only be able to watch the streamed service to avoid interacting with peers.

Only two British Masorti synagogues will be streaming services on the High Holidays this year, though as it happens they are the two largest: Shalev’s New North London Synagogue and the New London Synagogue, the movement’s oldest congregation. Both synagogues will be holding abridged in-person services with limited attendance.

From right, David Rabin, Talya Baker and Debbie Harris visit the tower of St. Albans Cathedral where they will blow the shofar on the second night of Rosh Hashanah. In the rear is the cathedral’s head verger, James Proehl. (Adam Zagoria-Moffet)

Recognizing that most congregants will only be able to attend a highly limited in-person service at best, and with most of its sister congregations eschewing livestreaming entirely, New North London has set to work on a range of supplementary programming, including a 50-page booklet to help guide community members through the holiday period. The book, which is being distributed around the country and translated for other European countries, aims to explain High Holiday basics to assist with home observance while offering innovative alternatives, like a meditation guide on the theme of repentance.

Synagogues are also ramping up their pre-holiday learning opportunities, including daily classes during the month of Elul, the Hebrew month leading up to Rosh Hashanah. Recordings of familiar holiday tunes are being uploaded to the internet so people can learn to sing them at home. And with communal shofar blowing posing unique health risks this year, congregants are being encouraged to make their own using a ram’s horn, a saw and a drill.

“You can get a ram’s horn on eBay,” said Joel Levy, the rabbi of Kol Nefesh Masorti Synagogue in north London. “I acquired 10 yesterday just to bump up our numbers.”

In St. Albans, Zagoria-Moffet has launched a web portal, DaysOfAwesome.uk, to guide his community through the holiday period, complete with a London-style Tube map to help them navigate among events organized along three tracks: prayer, community and learning.

Among his plans are a WhatsApp group with daily inspirational messages, a pre-holiday communal honey cake bake via Zoom and a virtual Rosh Hashanah Seder, a Sephardic tradition built around symbolic holiday foods. Zagoria-Moffet is also asking his community to write anonymous confessions on postcards and send them to the synagogue, a contemporary take on the practice of confession that is a hallmark of the Day of Atonement.

“I don’t know if this will work,” Zagoria-Moffet said. “If people don’t engage, then they get nothing. It’s this or nothing.”

But while a cloud of uncertainty hangs over the entire enterprise, rabbis are candid both about the imperfection of what they can offer and their hope that some of the creative ferment of this year will remain after the pandemic has passed.

“There might be that things happen this year that we choose to carry on and bring back into our lives,” Levy said. “I hope that we have an experience that is one we can draw on in the future.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.