(JTA) — In the world of New York architecture, Stephen B. Jacobs is known for his multimillion-dollar creations, such as the Hotel Gansevoort, a swanky boutique hotel with a rooftop bar that was the first luxury hotel in the city’s trendy Meatpacking District.

But Jacobs recently finished a much different project — and charged nothing.

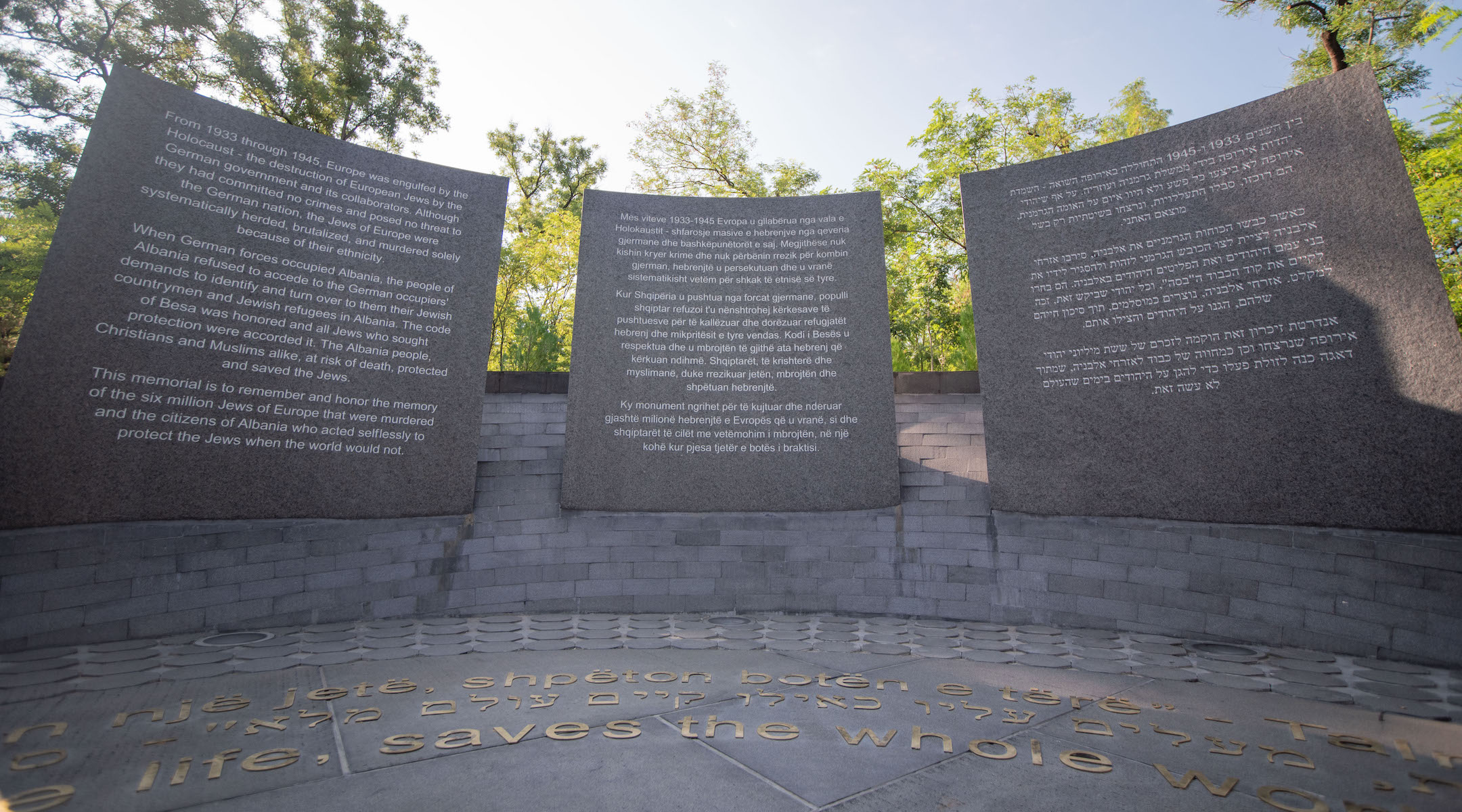

For several years he worked to design a Holocaust memorial for Albania’s capital. Unveiled last month at the entrance to the Grand Park of Tirana, the simple memorial features three stone plaques — in Albanian, English and Hebrew — that highlight the stories of Albanians who saved Jews during World War II.

Jacobs, 81, agreed to work on the memorial after learning that Albania was the only country in Europe that had more Jews after World War II than it did before. In addition to not handing over any Jews to the Nazis, hundreds of Jews fleeing other countries were offered shelter in the Muslim-majority country.

“I thought this was a very important story that needed to be told,” he said.

Jacobs’ latest memorial honors Albanians who saved Jews during World War II. (Courtesy of Jacobs)

His motivation goes beyond wanting to highlight the bravery of Albanians during the war. Jacobs himself is a Holocaust survivor who spent time in a Nazi concentration camp as a child.

“For me this is not simply about designing. This is sort of a personal experience,” he said.

Born Stefan Jakubowicz in the Polish city of Lodz, Jacobs and his secular family would move to Piotrków — a city that became home to the Nazis’ first ghetto. The ghetto, which housed 25,000 people, was liquidated in 1942.

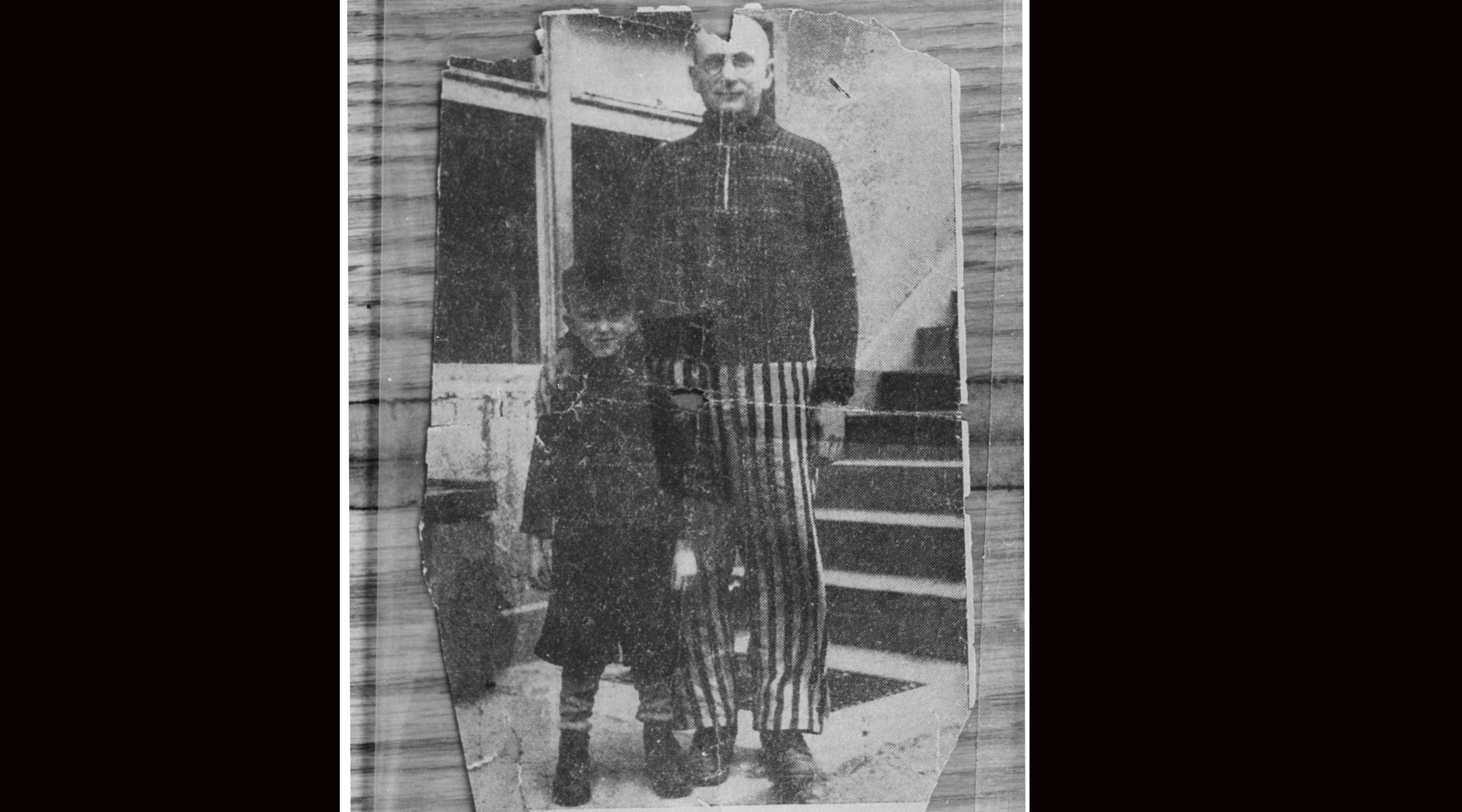

Jacobs and his family — his parents, older brother, grandfather and three aunts — eventually were sent to concentration camps. The males went to Buchenwald, the females to Ravensbruck. He was only 5 years old at the time.

At Buchenwald, Jacobs managed to survive both through luck and the assistance of an underground resistance that worked to save children. He spent his days at the shoemaker’s shop, which allowed him to get out of the daily roll call, where guards likely would have killed him because of his youth. Later he hid in the tuberculosis ward of the camp hospital, where his father was working as an orderly.

“I have fleeting memories,” Jacobs said. “I have memories that are not chronological, particularly the last few weeks because that was a very traumatic and dangerous time because they were trying to liquidate the camp.”

Miraculously, all of Jacobs’ immediate family survived the war, though his grandmother died shortly after the camps were liberated. The family left for Switzerland, where they lived for three years. In 1948 they moved to the United States, settling in New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood.

Jacobs would go on to become a prominent New York architect, founding his own firm and teaming with his interior designer wife, Andi Pepper.

His career ended up bringing him back to Buchenwald. He was commissioned to create a memorial for the “little camp,” a quarantine zone where new prisoners, including Jacobs, stayed in brutal conditions.

Jacobs agreed, with two terms: He would not take a payment because he did not want to be paid by the former camp, and “these are things you don’t do for a living.” The memorial was inaugurated in 2002, on the 57th anniversary of the camp’s liberation.

The Tirana memorial was far less emotionally draining, he said.

“Albania of course was more remote because I wasn’t there. I didn’t know much about Albania before. I certainly didn’t know the story,” Jacobs said. “Buchenwald was entirely different, so emotionally initially it’s difficult.”

Jacobs is seen with his father at the Buchenwald concentration camp. (Courtesy of Jacobs)

In designing memorials, Jacobs’ priority is ensuring that visitors leave with a greater understanding of the Holocaust. Like the Tirana memorial, the one at Buchenwald is relatively straightforward and features plaques with information about the camp and the places from where inmates were deported.

“Holocaust memorials tend to be one of two extremes,” he said. “They tend to be either the heroic Soviet-style memorial, the heroic resistance to fascism, or so totally abstract that the laymen viewer needs an explanation as to what it is he’s looking at, as an example [Peter] Eisenman’s memorial in Berlin.

“And I felt that neither of these directions was appropriate. The most meaningful thing about a Holocaust memorial, particularly since we’re doing this for future generations, is to tell people exactly what happened here.”

In recent years, Jacobs has been in the media not only for his architectural work but also for his harsh criticism of President Donald Trump. In a 2018 interview with Newsweek that received wide media coverage, he drew comparisons between the rise of the far right under Trump and prewar Germany.

“I think this is probably the most important election, certainly of my lifetime,” he said, going on to add that the outcome “will determine the future of this country.”

“Four more years of Trump and this country will not be recognizable,” said Jacobs, who supported Sen. Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign and said he will be voting for Joe Biden in November.

Jacobs, who splits his time between New York’s Upper West Side and the town of Lyme in Connecticut, still works as an architect. The coronavirus pandemic prevented him from attending the Tirana inauguration.

He said being able to design Holocaust memorials is cathartic for him — but that doesn’t mean he has forgiven Germany for its past. In fact, Jacobs recalls a German official saying at the inauguration of the Buchenwald memorial that his presence was a “symbol of forgiveness,” and being asked by a reporter about the comment.

“This is not about forgiveness,” he recalled responding. “For me, this is about closure. Everything has to come to an end, and that’s why this is such an important thing for me to do on a personal level.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.