This story originally appeared on The Nosher.

This may be surprising, but Jews have a long and very influential history in the alcohol industry spanning Europe, Israel and North America.

For most of the 1800s, Eastern European Jews held a virtual monopoly on the business in their regions. They produced much of the beer and hard alcohol, and ran nearly all the taverns where it was sold. Jews had been in the trade for centuries, but when Polish landowners saw they could make 50% greater profits by turning grain into alcohol than by selling it for food, Jews seized the chance to play an integral role.

At the time, Polish Jews could neither become nobility nor work the land as peasants. While many Jews turned to trading and peddling, the lords saw a different opportunity. Jews were considered good with business, they reasoned well, and would be unlikely to drink up the product. So, under a leasing system known in Polish as “propinacja,” Jews were granted exclusive rights to run the alcohol industries.

By the middle of the 19th century, approximately 85% of all Polish taverns had Jewish management. Jews similarly dominated the industry in the Pale of Settlement (in today’s Ukraine and Belarus), though on a slightly lesser scale.

Jewish participation in the alcohol business was so prevalent that according to Glenn Dynner, author of “Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, & Life in the Kingdom of Poland,” 30-40% of Poland’s Jews (including women and children) worked in the industry. That’s an impressive statistic by itself, but considering that approximately three-quarters of world Jewry lived in Eastern Europe at the time, that amounts to about 25% of all Jews in the world!

The quirk of the outsize Jewish population in the region is not all that accounts for the high percentage. That one-in-four figure is without even considering Jews in other parts of the world. But the 19th century seems to have been a peak time for Jewish involvement in alcohol worldwide.

In Hungary, we encounter many Jewish families prominently involved in wine production. The Zimmermans, for example, were among the famous and award-winning producers of Tokaj wine. (Their pre-Holocaust winery is now owned by one of the region’s top producers.) Similarly, the Herzog family produced such high-quality wine (alongside their beer and spirits) that Emperor Franz Josef appointed them his exclusive wine suppliers.

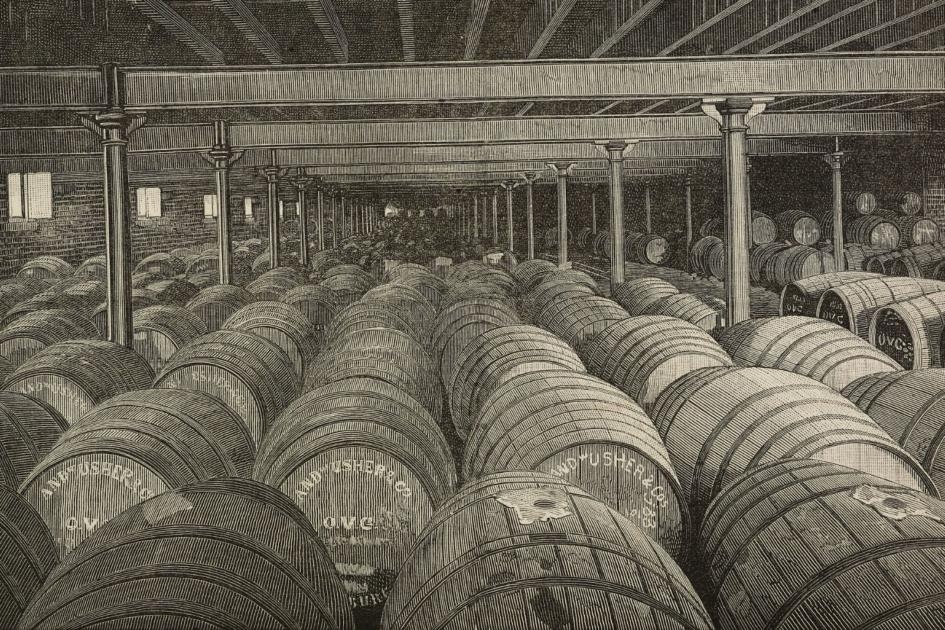

In Germany and France, meanwhile, Jews were dragging the local alcohol industries into the modern age. In France, Jewish wine producers were vertically integrating into sales as well, while in Germany, Jews created the first industrial-scale breweries.

Across the Atlantic, German Jewish immigrants to the United States were disproportionately represented in alcohol production. In “Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition,” Marni Davis points out that they primarily focused on distilling whiskey due to its “nationalistic significance.” Those who bought and drank whiskey “championed it as a deeply American product.”

Simultaneously, back in Ottoman Palestine, wine production was returning for the first time in hundreds of years. Though ancient Israel was well known as a wine-producing region, hundreds of years of rule by Muslims (for whom alcohol is forbidden) turned the industry into little more than a memory. But when more Jews began immigrating and joining the small community that was already living there, viticulture gradually returned.

In 1848, the Shor family opened a winery in the Old City of Jerusalem, adjacent to the Temple Mount itself. They were joined in the business in 1870 by the Tepperbergs and in 1889 by the winery later to be known as Carmel. These laid the groundwork for the booming wine industry that exists in Israel today.

Why were so many Jews prominently involved in the alcohol business during the 19th century? It was a period of transition in the world, with industrialization leading (among other things) to a big increase in alcohol production and consumption. At the same time, the old persecution of Jews had removed many other income sources, leaving Jews with few other ways to make a living. So part of the answer may be that, as had been the case so many other times throughout history, Jews simply took advantage of whatever opportunities they had, and succeeded.

Jews rapidly left the business toward the century’s end, thanks to both increased competition and government oppression, leaving this chapter in our history largely forgotten. Furthermore, even while Jews were prominent in the industry, there was an internal stigma against Jewish involvement in a profession that was seen as less than honorable and at times required the use of some loopholes to remain in compliance with Jewish law. In other words, the Jewish community also forgot because it wanted to forget.

Interestingly, however, many common Jewish surnames today indicate a connection to the alcohol profession: Kaback, Kratchmer, Schenkman, Korczak, Vigoda, Winick and Bronfman, to name a few. Plus, many of the alcohol businesses run by 19th-century Jews still exist, including the Israeli wineries, Loewenbrau Brewery, Herzog Winery and Fleischmann’s Spirits.

While the legacy of Jews’ role in the alcohol business may be partly forgotten, the impact is far from gone.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.