(JTA) — When Neil Krieger was a graduate student at Harvard University in the mid-1960s, he decided he had to do something about racism.

Not content to watch from the sidelines as others battled for civil rights, he joined the Boston branch of the Congress of Racial Equality and began visiting local businesses, imploring them to hire African-Americans.

“They would go to a bank and see there were no black tellers, so they would meet with the head of the bank and tell him, ‘You should find a black teller,'” said his daughter Hilary Krieger, an editor at NBC News. “And they would find candidates who could do the job.”

“They weren’t trying to shame people or cause trouble, but to make a difference in the lives of the people,” she added.

Krieger, who died on April 29 in Boston from complications of COVID-19 at 78, was born in Spring Valley, New York, in 1942 to parents who ran a series of restaurants. He spent his teen years living in the storied Hotel Bossert, also known as the Waldorf-Astoria of Brooklyn. The hotel was a favored hangout of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and two members of the team actually attended Krieger’s bar mitzvah.

After graduating from Cornell University, he went on to earn a doctorate in biochemistry from Harvard and found West Rock Associates, a Boston-based consultancy that helps biotechnology startups obtain funding. He also served on the faculty of the medical schools at Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania.

“He had a very tough childhood in many ways, and the type of childhood you would not expect a person to go on [from] and be a model of what it means to be a great husband and father,” Hilary Kriger said. “But my dad wanted to be a great husband and father, so he carved his own path and didn’t let how he had been raised or his experiences define what would matter for him and how he would be toward other people.”

She said that he had a wicked sense of humor, noting that he coined the word orbisculate to describe the feeling of getting the juice from a citrus fruit in your eye.

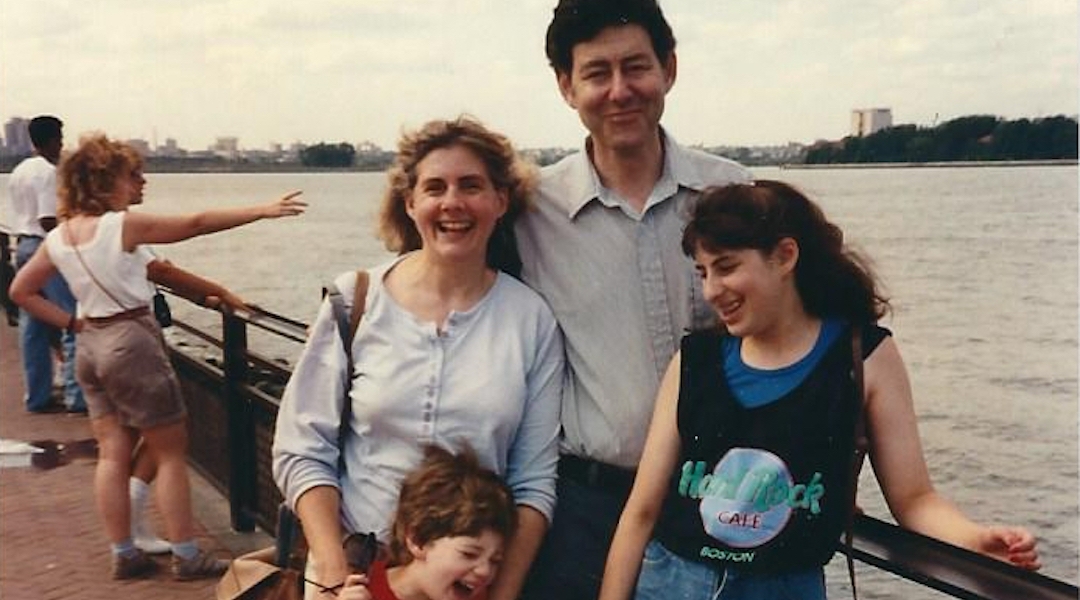

“My dad enjoyed a long, full life,” she wrote in a remembrance published on the NBC News website on May 27. “It was the one that he wanted, and he lived it on his terms, prioritizing his love for his wife and children and friends over making money or earning accolades. And he expressed that love — and laughter and tears and frustration and whatever other emotions came along — so that every moment and every relationship were experienced in their fullness and nothing was left unsaid.”

Krieger is survived by his wife, Susan, and children Hilary and Jonathan.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.