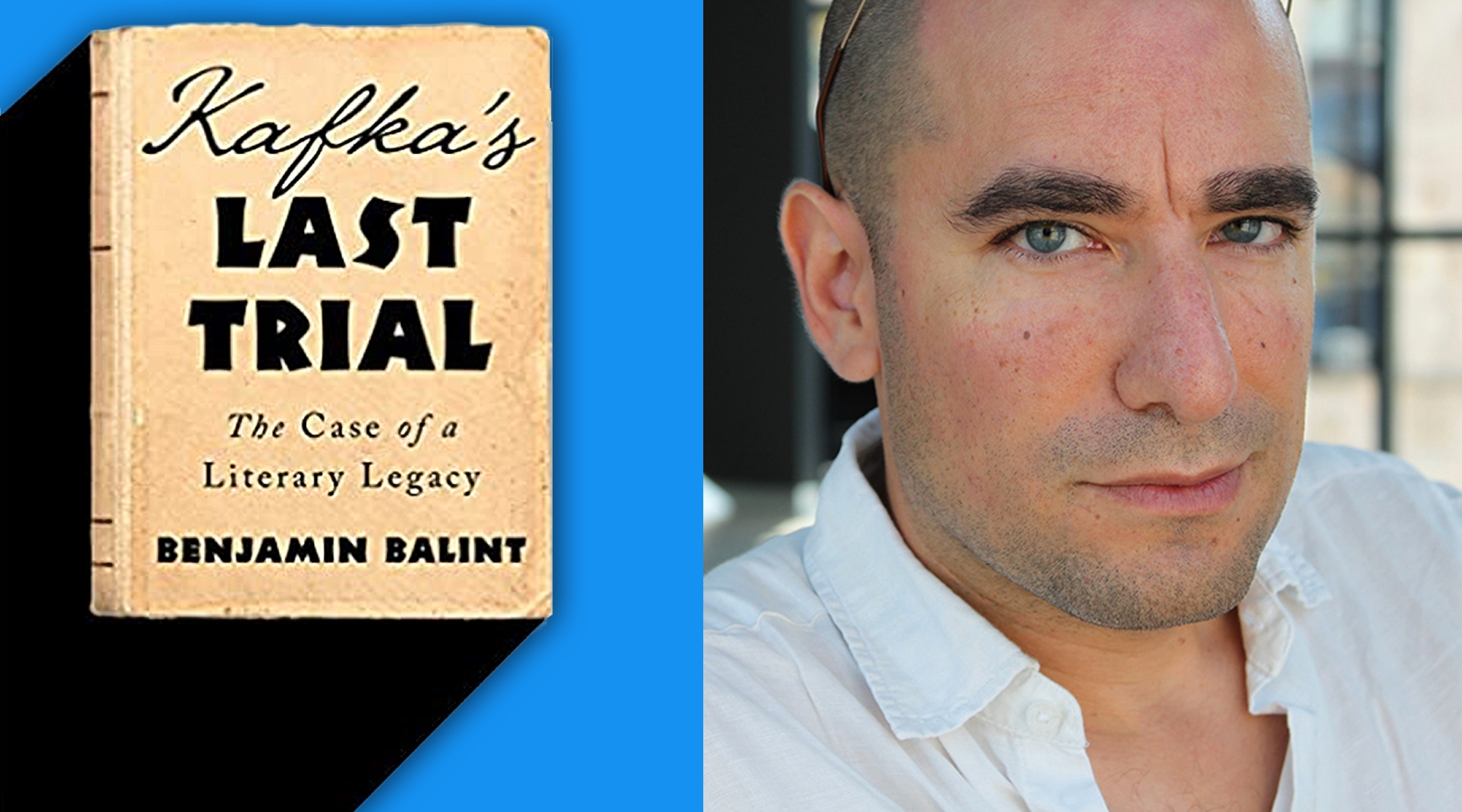

As Benjamin Balint asks in the epilogue to the paperback edition of “Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy,” which was published last fall, “Long before the trials in Israel, legion are those who have sought to claim Kafka. What is it about this writer, whose very name has become an adjectival cliché, that allows so many interpreters to appropriate and misappropriate Kafka’s legacy?”

Balint’s book — just awarded the 2020 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature — tells the story of the 2016 Israeli Supreme Court case that decided the contested fate of Kafka’s papers and unpublished material, along with the papers of Max Brod, his literary executor and the curator of Kafka’s posthumous fame. Years earlier, Kafka had asked Brod, another Jewish German-speaking Prague writer and his closest friend, to destroy all of his papers upon his death. But when Kafka died in 1924, Brod could not do it, and instead devoted his energies to publishing Kafka’s unfinished novels and promoting his international literary standing.

In fine detail, Balint tells the backstories to the trial, insightfully capturing the personalities involved as well as the complex legal, ethical and political issues; he delves into deep questions of artistic legacy, identity and, as it still pertains to the matter, the Shoah.

The Jewish Week spoke with Balint by phone last week at his home in Jerusalem. The author of two previous books, “Jerusalem: City of the Book” (with Merav Mack) and “Running Commentary,” he is a library fellow at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem and has written for The Wall Street Journal, the Jewish Review of Books and The Weekly Standard. He made aliyah in 2004.

What was the inspiration for taking on this project?

In 2010 I participated in a German-Israeli exchange program for writers, where I worked on the culture pages of the weekly paper, Die Zeit. This was still the early stages of the trial, and I became intrigued and kept up with it as it wound its way to Israel’s Supreme Court. When I returned to Israel, I was able to convince Eva Hoffe [the daughter of Brod’s longtime secretary, who had inherited the papers] to speak with me. Then I realized that in this book I could tell the stories of the three interested parties: the Hoffe family, the National Library of Israel and the German Literature Archive in Marbach, Germany.

What was your experience like in the courtroom?

I think the judges in this case could not help but act, maybe unwittingly, as the latest of Kafka’s interpreters. When I sat in the Supreme Court chamber, I understood that their verdict can be read as another reading — or misreading — of Kafka; as the latest page in the long history of the uses of Kafka’s literary afterlife at the hands of those who claim to be his heirs. I tried to read the judges’ opinions, which run 60 to 70 pages, as if they were literary documents. They’re not just pronouncing on legalistic questions, but on fundamental questions like whether Kafka was a German-language writer who happened to be Jewish, or essentially a Jewish writer who happened to be writing in German.

How did you get Eva Hoffe to speak with you, after she avoided journalists for so long?

Without meeting her, some journalists had portrayed Eva Hoffe as an eccentric cat-lady or greedy opportunist. Eva sensed that I could give a sympathetic hearing to her side of the story, and that I would be evenhanded. She was a deeply sympathetic and intelligent woman who felt she was being disinherited of that which connected her to her mother, Esther and to Max Brod, who had been a beloved father figure to her, and to her own past. In her view, the legal proceedings were nothing more than a pretext for state seizure of private property — in effect, an attempt to nationalize her most precious belongings. She fought that attempt to the last, but her life ended under the specter of defeat. [She died in 2018.]

These days, do people in Israel know of Max Brod?

Not nearly enough. On his 80th birthday, Brod said: “I dream that my autobiography, which has already appeared throughout the world, will be translated into Hebrew as well. … I so wish that Israeli youth would get to know me a bit more!”

Brod was much more prolific than Kafka [in his lifetime]. I recently wrote introductions to two of Brod’s novels, published by Aspal Press, that are only now appearing in English for the first time, and I hope that Brod will emerge from under Kafka’s shadow as a Jewish cultural figure in his own right.

What surprised you as you got more deeply involved in this case?

While it is quite well known that Kafka was ambivalent about Zionism, it became clear to me how devoted he was to the Hebrew language. I had a chance to leaf through his Hebrew vocabulary notebook, now at the National Library.

Is this the last of this story?

The story is ongoing. Last May, for example, 5,000 pages from Brod’s private archive, which had apparently been stolen from the Hoffe home in Tel Aviv, were handed over to the Israeli ambassador in Berlin. After the stash had been seized [from the Israeli Embassy] by the German Federal Police, a secondary trial in Wiesbaden, Germany, concluded that the stolen papers must be transferred to the National Library of Israel.

From the first, the [Israeli] trial raised questions about how Germany’s claim on a writer whose family was decimated in the Holocaust is entangled with the country’s postwar attempt to overcome its shameful past. But the trial also reawakened a long-standing debate about Kafka’s ambivalence toward Judaism and the prospects of a Jewish state — and about Israel’s ambivalence toward Kafka and toward diaspora culture. So the judges in Jerusalem may have reached their verdict, but those questions will continue to be meaningfully asked for a long time to come.

In this digital age, does it really matter where papers are housed, as long as all have access?

Given how hard Germany and Israel fought for these papers, they must have believed that even in the digital age physical ownership confers some kind of national prestige. Maybe modern technology creates an appetite for the authentic “originals” even when everything is accessible online.

What was your experience like teaching Kafka to your Palestinian students at Al-Quds Bard College of Arts and Science in East Jerusalem?

Those students taught me new and contemporary facets of the Kafkaesque universe. One student wrote a final paper in which she discussed her own family’s experience — they were engaged in a years-long struggle to save their home in Jerusalem’s Old City from confiscation by the state, a case that ended up going all the way to the Supreme Court. She compared her own family experiences with the experience of Josef K. in Kafka’s “The Trial,” in a very brilliant way. She had never heard of Kafka before, but I had the feeling that reading Kafka gave her a new vocabulary to express what she was going through.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.