JERUSALEM (JTA) — Nearly six weeks have passed since Arie Even, an 88-year-old Holocaust survivor, died of the coronavirus.

It happened at the end of Shabbat dinner on a Friday night in March at the Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem.

Even drew headlines as Israel’s first COVID-19 fatality. As of Thursday, the coronavirus death count in the country had risen to 222. There have been almost 16,000 confirmed cases.

For Rachel Gemara, 33, the memory of Even has not lost its charge. It’s stark and raw, and may stay that way for a long time to come.

She was the veteran nurse on call that night monitoring Even’s breathing when he had a heart arrhythmia in Keter Alef, the hospital’s first popup unit created for corona patients. The monitor sounded a long solemn beep, and the doctors raced to don their gear and care for him.

Gemara watched Even gasp and wheeze his last breaths on the screen as his grip on life slackened. She felt the tears stream from her eyes. Two patients in the isolated coronavirus ward raced to Even’s bedside, placed their hands on his eyes and recited the Shema, the Jewish declaration of faith. Even had passed away.

Gemara understood that she and the other nurse on call would have the inauspicious responsibility of being the first ones in Israel to wrap the body of someone who died of the virus over fears of contagion. Because the resilient pathogen remains in a decedent and could be expelled in bodily fluid when the body is moved, this involved implementing a protective protocol drafted by the Israeli Ministry of Health just eight days earlier.

Gemara reached for the special kit, which included two bags and four pages of instructions.

***

Preparing a body for Jewish burial is habitually the domain of the chevra kadisha, Hebrew for “holy society.” The ritual act of purification is known as tahara, which is carried out by individuals trained to care for the body in an age-old process of traditional cleansing. Men care for men; women care for women. It is said that the body is treated as a vessel for holiness.

The specific rituals for care of the dead are generally relegated to the private domain. The body is washed thrice in a constant stream of warm water or ritually immersed in a body of water before it is dressed in “tachrichim,” a traditional Jewish burial shroud of simple white intended to be a cocoon of sheets. Silence fills the room, save the recitation of psalms and prayers. The deceased is addressed by name.

Gemara had spent 10 years in an oncology ward where most of the patients are at the severe stage 4 and approximately 30 percent are terminal. She had invested emotionally in making their end-of-life meaningful and caring for them when they passed on.

By nature, Gemara gravitated to the demanding. Right out of nursing school, she had advocated to work in oncology. That same drive prompted her to volunteer for the not-yet-formulated unit for coronavirus patients in late February, as a text circulated in the hospital calling for staff members to sign up.

Gemara’s knack for compassionate care meant that she instinctively knew what to do when a patient passed away. She also had considerable experience with patients postmortem.

“How many times had I wrapped a body? 100 times? 200 times?” she said.

But wrapping a body in a special bag and cleaning it to avert endangering those with whom it would come into contact until burial? That was a first.

Even more piercing was the knowledge that she’d be the last one to identify and care for him. That, too, was uncharted territory.

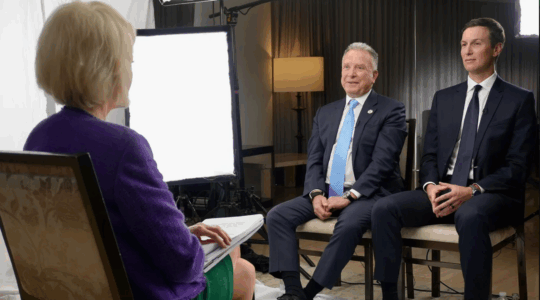

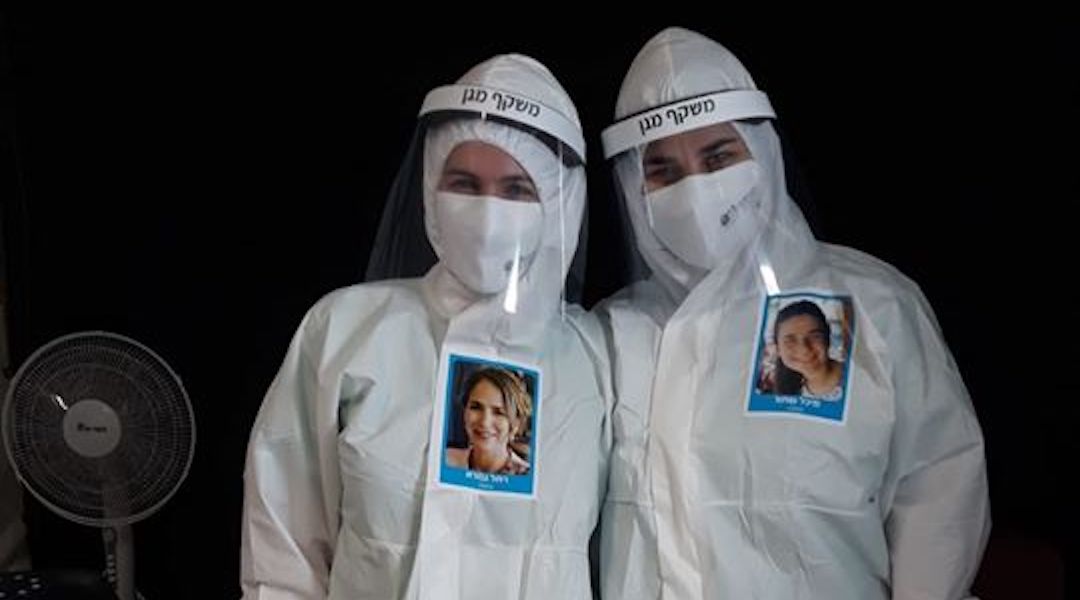

Shaare Zedek staffers feature photos of themselves on their protective suits. (Courtesy of Gemara)

On that Friday in March, Gemara slipped out of the hospital into the parking lot and stepped into a white hazmat suit, then zipped it up. She pulled her long hair into a ponytail, put on an N95 mask, two sets of blue sanitized gloves, face shield and hood, and slipped booties over pink Nikes. Cuffs secured. It took 10 minutes to don the protective gear. Then she buzzed into the unit.

As she started to care for Even’s body, her eyes stung with tears. He reminded Gemara of her grandparents, Saba Dov, 96, and Savta Miriam, 90. Like Even, they were Holocaust survivors from Hungary and spoke with the same accent.

“He was familiar,” she remembered recently, her voice shaking with emotion.

Even had escaped the Nazis by hiding with his mother and brother in a countryside basement, helped by the renowned Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. Even had survived multiple heart attacks and surgeries, even fled a cholera epidemic in Spain. He had four grandchildren and 18 grandchildren. A great-grandchild was born. He had lost his wife of 50 years, Yona, in 2012.

When Even had teetered in to the hospital on his weathered brown cane five days earlier, his skin pale and hair matted, he was short of breath, chest rising. His eyes took in the room grimly.

***

On Monday, Even had asked Gemara to help him call his family members to say goodbye. By Friday night, he was rapidly deteriorating.

That evening was Gemara’s seventh day in the unit, her fifth shift there. On the corona-compressed calendar, time seemed to stretch and contract.

Gemara is a Modern Orthodox Jew, the daughter of a rabbi. Born in Israel, she was raised in Toronto before moving to Jerusalem in 2006.

Judaism provided an anchor, a way of life. She felt viscerally pained over the fact that Even would not experience the proper end-of-life Jewish rituals.

“In addition to the COVID-induced isolation of dying without family, this man who survived the Nazis was going to be cheated out of this,” she reflected.

Then Gemara understood that she could be his makeshift chevra kadisha. She could confer respect to the dead. While she wrapped the body as prescribed by the Health Ministry, she imbued it with the same holiness and intent of tahara. Modified, atypical holiness. But holiness nonetheless.

When she was done, she replicated a custom of the burial society: appealing to the body for forgiveness if any distress was caused in the preparation. Inaudibly and with reverence, she whispered:

“Arie, I’m sorry for how we were required to handle your body. We did our best to preserve your dignity and respect you in the current circumstances. … It was a tremendous honor to care for you in your final days. You’ve touched my heart, the staff, and the patients that surrounded you. I know your life will inspire the rest of ‘Am Yisrael’ [the Jewish people] as well. Go to your resting place in peace. Look out for us from above.”

The following evening, Even was buried by members of the chevra kadisha wearing biohazard suits, with only his youngest child able to attend. Jewish end-of-life rituals had to be secondary to safeguarding the living.

***

As the pandemic continues, so does grappling with end-of-life customs and practices. Tahara was suspended, then permitted.

The coronavirus has blurred other kinds of lines: Patients care for other patients in a closed-off ward while medical staff observes from afar. Doctors and nurses are suited head to toe, their faces trapped on the inside while smiling glossy photos of their faces are plastered on the outside — something to reveal about the health professional inside.

Over the past six weeks, Keter Alef sprouted to six units, including one in the ICU. In that time, Gemara clocked 275 hours in 12-hour shifts. She celebrated her 33rd birthday and a Passover Seder. Much of her life has been all coronavirus, all the time. No breathers with friends, no time to jog, no respites to condition her hair. She found restful sleep to be a distant country.

Rachel Gemara celebrates Passover at the hospital. (Courtesy of Gemara)

When she did nod off, her dreams were dark and unreachable. Many times the responsibility felt heavy, unyielding.

Fortunately the rate of incoming patients has slowed. With cautious optimism, Shaare Zedek closed Keter Hey on April 23 and Keter Bet on April 26. Keter Alef shuttered on April 30. Things were starting to open up.

But the ache of losing Even lingered.

Then it was bookended by hope.

***

On the evening of April 23, a tall man with glasses knocked his glove-covered hand on the nurse’s station. Gemara’s face beamed. It was her patient, admitted three weeks prior with severe respiratory distress, too weak to get out of bed.

The 51-year-old with no prior medical conditions had stopped breathing on her watch. As she revisited that night, her voice caught.

“At 2 a.m. I was inside the unit, in full protective gear, the rest of the staff far away in the headquarters,” Gemara recalled. “He asked me to help him out of bed, and as I slowly helped him sit down, he suddenly slumped his head, his eyes rolled back and he completely lost consciousness.

“I was alone and terrified. His life was in my hands, and every second counted. I leaped to grab a 100% oxygen face mask from the crash cart and connected him immediately to the maximum amount of oxygen. Thank heavens he regained consciousness. The sheer terror and uncertainty of those few moments shook me to my core.”

As she looked at him, Gemara remembered wheeling him carefully to the ICU Keter Unit, eyeing him closely during the transfer. How she’d squeezed his hand, saying “Stay strong, keep fighting, I’ll pray for you and I’ll see you again soon.” How she’d walked back to her unit in tears, wondering if she would, in fact, see him again soon.

And now he had come to say goodbye.

“Hey there,” he said, release papers in hand, looking straight into Gemara’s eyes. “I just wanted to thank you. You saved my life, plain and simple.”

This article was made possible with the generous support of UJA-Federation of New York. For additional resources related to Judaism and end of life care, death, and mourning, click here.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.