(JTA) — To many British Jews, the election of Keir Starmer as leader of the Labour Party this month has been greeted as an end to four years of fear and disappointment under his predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn.

Starmer is a 57-year-old prosecutor-turned-politician whose wife is Jewish and who has said he wholeheartedly supports Zionism. Immediately after his election on April 4, Starmer acknowledged that Labour had failed to address its anti-Semitism problem under Corbyn for years.

With the far-left anti-Israel campaigner Corbyn at its helm, Labour was fractured by multiple scandals and lost the support and confidence of a large portion of the country’s Jewish population.

Three weeks into his leadership, however, Starmer has begun to walk a tightrope — between flushing out the anti-Semitism controversy and appealing to the large number of the party’s Corbyn loyalist holdovers — that has given some British Jews reason for concern.

Starmer has already promoted three lawmakers with strained relationships with the Jewish community to leadership positions.

Afzal Khan, Starmer’s pick for shadow deputy speaker of the House of Commons, the lower house of the Parliament, once shared a link on Facebook to an article titled “The Israeli Government are acting like Nazi’s [sic] in Gaza.” In 2015, Khan shared a video on Facebook with captions about the “Israel-British-Swiss-Rothschilds crime syndicate” and “mass murdering Rothschilds Israeli mafia criminal liars.” He later apologized, but then reportedly claimed the video was not anti-Semitic.

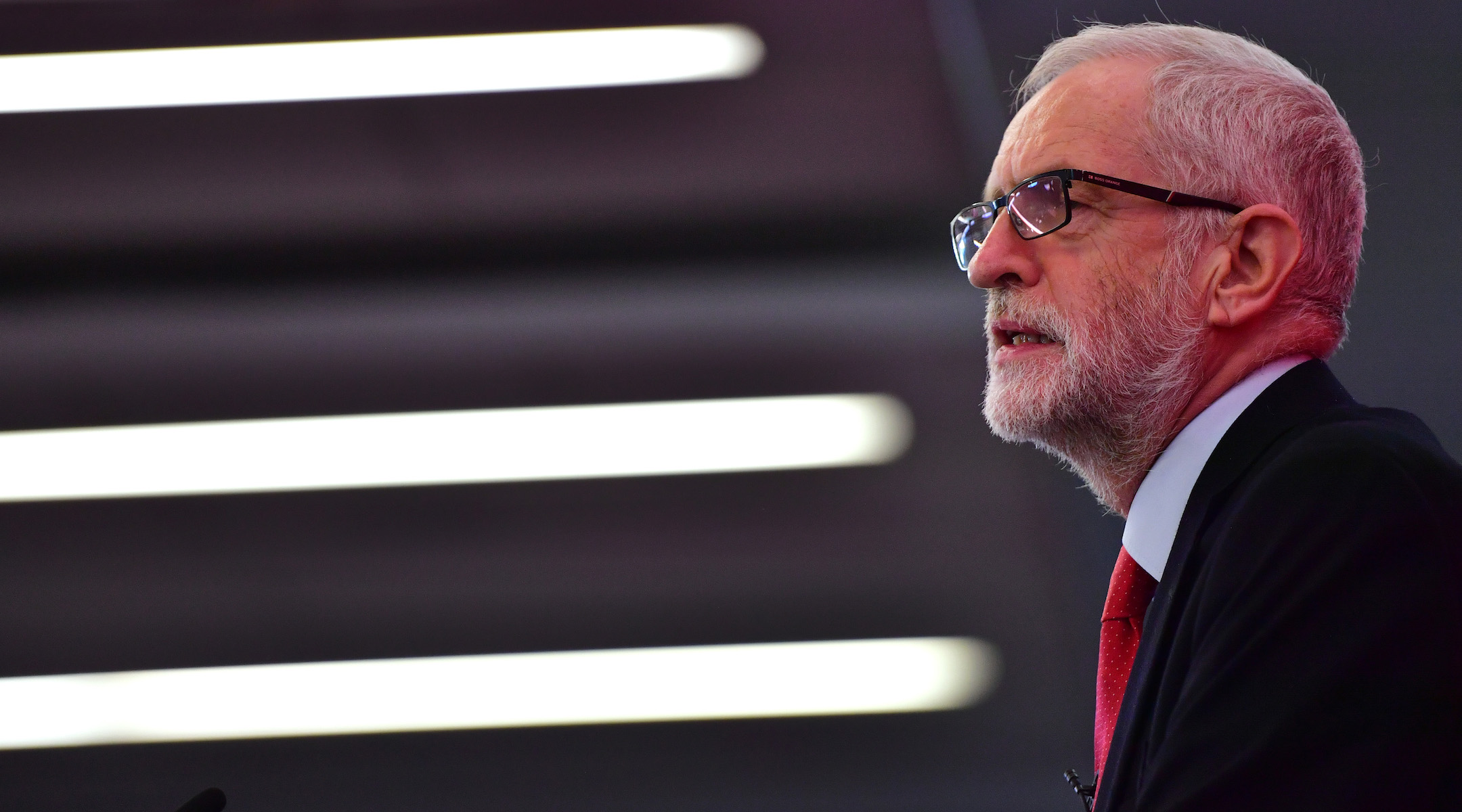

Jeremy Corbyn, then the head of the British Labour Party, speaks at the University of Lancaster, Nov. 15, 2019. (Anthony Devlin/Getty Images)

Lisa Nandy, Starmer’s shadow foreign secretary, is chair of Labour Friends of Palestine and the Middle East group, an internal lobbying platform. She has expressed support for fighting anti-Semitism within Labour but has endorsed on several occasions the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, a group whose Facebook and Twitter accounts often fail to delete the rampant anti-Semitic rhetoric on their pages. She also signed on last year to a platform that calls for the “return of Palestinians” to the State of Israel — a demand Israel’s advocates say is a euphemism for ending the world’s only Jewish sovereign nation.

Lloyd Russell-Moyle, Starmer’s pick for point man on the environment, in 2017 called for reinstating a Labour activist, Melanie Melvin, who had been suspended for claiming that the BBC faked footage of a Syrian gas attack at the behest of the “Israeli lobby.”

Last week, the Campaign Against Antisemitism, a major communal watchdog, published an analysis of the track records of 32 of Starmer’s nominees for top party positions. The Campaign said that it said shows that Starmer “is not showing zero tolerance to antisemites.”

“He will find his honeymoon short-lived if he delays the hard decisions and actions that are necessary,” the Campaign added in its report.

Labour Against Antisemitism, a group inside the party that grew out of opposition to Corbyn, wrote in a statement that Starmer’s nominations “leave unanswered questions” on Starmer’s commitment to fight anti-Semtism and that “despite some positive signs,” he is “as capable of making inappropriate appointments as his predecessor.”

Starmer’s team did not reply to emails and a telephone query asking for a reaction to these allegations.

However, people with inside knowledge of internal processes within Labour disagree with the assertion that Starmer is reverting to a Corbyn-like system.

Starmer, left, is with Jeremy Corbyn at the European Union headquarters in Brussels after a bilateral Brexit meeting, Sept. 27, 2018. (Thierry Monasse/Getty Images)

“The nominations look bad, but it’s actually a reflection of limited choice,” said one pro-Israel party activist, who spoke under condition of anonymity.

Following last year’s elections, Labour now has 202 lawmakers in the Parliament — its fewest since 1935. At least 12 former lawmakers had left Labour under Corbyn.

“This means that Starmer is limited. He needs to nominate dozens of MPs, and there are fewer to choose from, so he needs to make compromises,” the activist said.

Labour, which was established in 1900, has dozens of positions that must be filled — the activist says at least 100 — with its lawmakers.

There’s also the trickier task of appealing to the Corbyn supporters who still make up a sizable portion of the party’s base and governing infrastructure. At least 100,000 members joined under Corbyn, constituting about 17% of 580,000 members in total.

“[If] Corbyn loyalists are made to understand they have no place in Labour under Starmer, that’s simply making sure they’ll misbehave,” the activist said.

Gideon Falter, the executive chief of the Campaign Against Antisemitism group, acknowledged these constraints. But while they may explain Starmer’s calculus, they also illustrate how “Corbyn’s poisonous legacy of anti-Semitism has so permeated the Labour Party that there are too few untainted figures amongst its parliamentarians to fill even these few coveted posts,” he said.

Despite the appointments, Starmer has taken several strong steps to distance himself from Corbyn and the scandal that marred his tenure. British Jews have noticed.

Four days into Starmer’s leadership, the president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Marie van der Zyl, said in a statement that he had achieved “more than his predecessor in four years in addressing antisemitism within the Labour Party.”

The previous day, Starmer had removed Corbyn nominees from Labour’s governing body, the National Executive Committee. It ended the pro-Corbyn majority in that forum.

Within days of winning the internal elections, Starmer had also set up meetings with leaders of major Jewish groups in a stated effort to mend relations that had effectively been frozen under Corbyn, whom the previous chief rabbi of Britain, Jonathan Sacks, has publicly called an anti-Semite.

Starmer additionally demoted Richard Burgon, a Corbyn loyalist who in 2014 said that “Zionism is the enemy of peace” and who has declined to endorse the party’s own definition of anti-Semitism. Burgon was Corbyn’s shadow justice secretary, the party’s point man for the justice portfolio.

Starmer didn’t say why he sacked Burgon, but many understood it as a powerful statement on the seriousness of his stated intention to clean up Labour’s act.

Critics of Labour’s handling of anti-Semitism have called for years for Burgon’s removal from positions of influence. Mark Gardner of the Community Security Trust, British Jewry’s watchdog on anti-Semitism, wrote in a Jewish Chronicle op-ed from February that Burgon’s remarks “show how deep Labour’s antisemitism problem runs.”

The new leader’s rhetoric on anti-Semitism is also different than his predecessor’s. While Corbyn had apologized after much internal pressure, he never directly acknowledged that the distress for which he was apologizing was genuine — a fact that for Jews added extra sting to the whole scandal. Corbyn had also always insisted that Labour had tackled anti-Semitism firmly and fairly under his leadership.

Starmer, in comparison, has spoken in direct terms.

“I know that the failure of the Labour Party to deal with anti-Semitism has caused great grief in Jewish communities,” Starmer said in a video greeting for Passover on April 8, in which he apologized for the failing.

“If you are anti-Semitic, you cannot and should not be in the Labour Party. No ifs, no buts,” Starmer wrote in an April 7 op-ed published in the Evening Standard. “I will leave no stone left unturned in the fight against anti-Semitism. That is my promise to the Jewish community.”

He added that this is “a moral imperative, not a political one.”

“This is not Corbyn continuity. And that’s huge,” said David Hirsh, a senior lecturer on sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London and author of the book “Contemporary Left Antisemitism.”

Starmer’s wife, attorney Victoria Alexander, comes from a Jewish family and has family in Israel. Starmer told the Jewish News that he hoped to travel soon to Israel with their two children.

“I absolutely support the right of Israel to exist as a homeland,” he told the newspaper, and “I support Zionism without qualification.”

Starmer led the Crown Prosecution Service, the main public criminal prosecution agency for England and Wales, for five years until 2013. In 2015, he took up a top spot within Labour under Corbyn as the party’s point man about Brexit.

Even back then, Starmer’s track record on anti-Semitism indicated that he did not see eye to eye with Corbyn on the issue.

At a time when Corbyn was trying to get the party to reject the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of anti-Semitism because it lists some examples of Israel hatred, Starmer publicly said the party should adopt that definition.

“I believe in the full definition. Councils, institutions across the country have accepted the full definition. I think that’s the right position to be in,” Starmer said in a BBC interview in 2018.

Whereas Corbyn insisted on an individual review for anyone accused of ant-Semitism, Starmer called for automatic punitive action.

“I would support a rule change that says you expel in clear cases of anti-Semitism automatically, just as we do for people who support another political party in an election,” Starmer told the BBC last year, when he was shadow Brexit secretary and formally prohibited from diverging from the party line.

He also issued what had been his strongest criticism of Corbyn prior to his election in that BBC interview.

“Be very clear: If you deny we’ve got a problem, that’s part of the problem,” Starmer said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.