CHICAGO (JUF News via JTA) — Are American Jews weird?

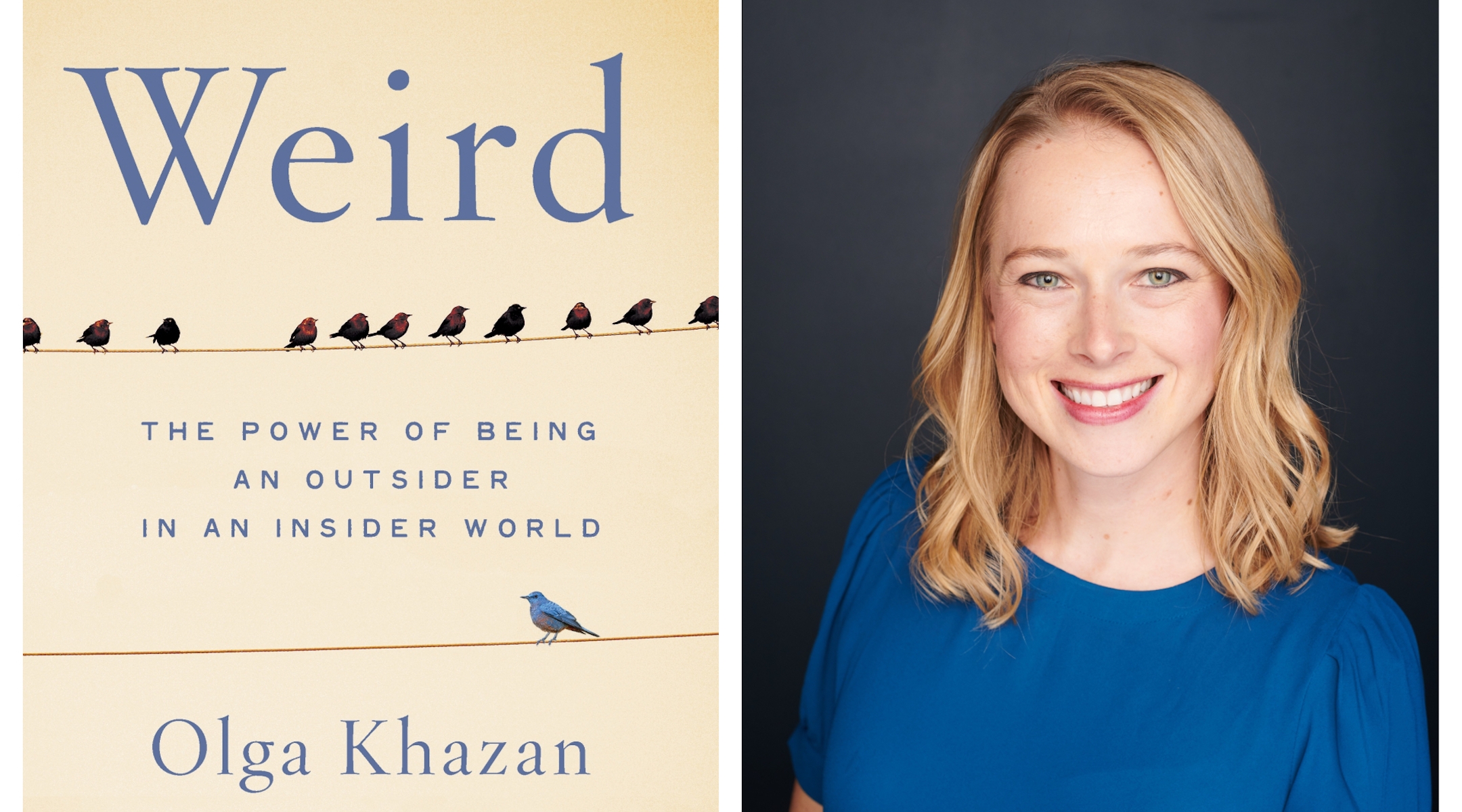

It’s a question that Jewish readers may ask themselves while immersed in Olga Khazan’s just published “Weird: The Power of Being an Outsider in an Insider World,” a meditation on what it’s like to be different in a world that more often than not seems to prize group think and cultural conformity over variations in race, sexual orientation, religion and nationality.

So, yes, by those defining parameters, most American Jews would be considered weird, at least if they haven’t spent most of their lives in heavily Jewish enclaves.

Asked whether she thinks Jews are weird, Khazan, a Washington, D.C.-based staff writer for The Atlantic, was political in her response.

“That’s an interesting question,” she said. “I can see how you might see it that way.”

Khazan was far more direct in talking about her own “weirdo” status, which was the catalyst for her debut book.

As she details in “Weird,” she came upon this self-designation honestly after years of awkwardness and social isolation. A product of the former Soviet Union, Khazan left the country with her parents when she was a tot — just a year or so before the USSR’s dissolution and at the cusp of the massive exodus of Soviet Jews to Israel and the United States.

Khazan’s family was already “different” than most of the other Soviet emigres at the time. As she notes, only her father is Jewish, while her mother is the Finnish-born daughter of Lutheran farmers. On top of that, the Khazan family, unlike like so many of their cohorts, settled not in a large metropolitan area but in the West Texas city of Midland, which had nary a Russian immigrant, much less a Jew.

From the start, the author’s experiences in Midland reinforced differences between her and her peers. She recounts a scarring incident at a Baptist-run day care center, where as a 4-year-old she indulged in a snack without saying a blessing.

“A daycare worker saw me, asked, “Are you eatin’ without prayin’!?,” she writes, “and punished me on the spot. I didn’t know how to tell them that I’m from somewhere else, that I don’t believe what they do. … When my mom came to pick me up, the daycare instructor complained to her about my misbehavior. My mom said nothing (‘We were afraid. We were new,’ she says now. ‘It was a small town. Everyone knows each other. We were trying to play by their rules.’).”

Khazan continues, “Someone told me, around this time, that I was an ‘alien,’ like E.T. That day, it felt more true than ever: like I had traveled to a new planet, and I’d never learn to breathe its air or speak its tongues.”

While alienated from the prevailing mores of Midland and later of suburban Dallas, where her family moved during her adolescence, Khazan tried desperately to fit in, going so far as to attend an evangelical Christian Sunday school and youth group.

“I was very uncool and had no friends,” she recalled, and “if you’re someone who struggles socially,” a church group, with built-in rules and standards of behavior, seemed like an expedient answer.

Growing up, Khazan never disclosed her father’s religious background to acquaintances.

“I didn’t want to throw the Jewish thing” into conversations, she said. “It was yet another thing” — in addition to her family’s foreignness and accents — that would make her stand out.

For a school genealogy project, when she learned that her surname means “cantor … some sort of singer in a synagogue,” Khazan admitted to herself that “I was jealous of the girl whose last name was Welsh for ‘stone,’” she writes in the book.

For “Weird,” Khazan dug deeply, combing through the academic literature about “differentness” and the emotional fallout for those who have been made to feel inferior because of it. She also conducted interviews with “weird” individuals, who shared their own challenges and coping strategies.

After many years as a successful writer, does Khazan feel that she can now wear her “weirdness” as a badge of honor?

“I think I’m more comfortable being different,” she said. But as for differentness being a point of pride, she added, that remains “aspirational.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.