TEL AVIV (JTA) — “Where’s the Chagall?” asked a visitor to this city’s Gordon Gallery on a January morning in 1996, hoping to glimpse one of the prize lots being auctioned days later by the gallery.

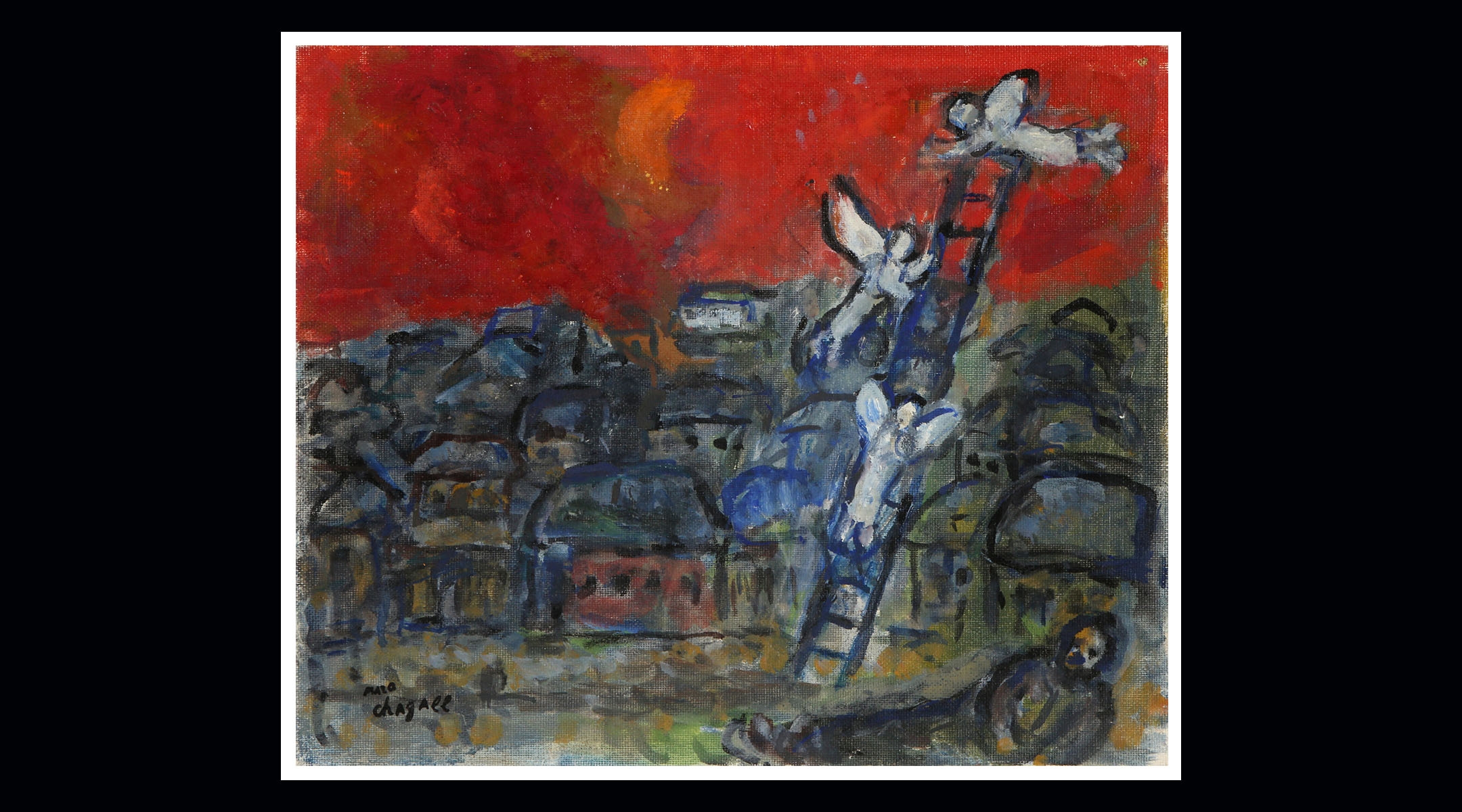

The painting, titled “Jacob’s Ladder,” was prominently on display, but still a gallery employee walked the prospective buyer over. When they arrived at the work’s designated spot on the wall, all that remained was a bent nail. The Chagall was gone.

For nearly two decades, the painting remained missing. Now it’s on public view for the first time in 24 years, again as part of a pre-auction exhibition, this time at the Tiroche Auction House in Herzliya. The small, biblically themed canvas that will be offered for sale this week as Lot 99 is notably installed in a glass case in Tiroche’s showroom north of Tel Aviv, one of hundreds of works that are part of the auction house’s Israeli and International Art Sale.

The painting by the famed Jewish modernist Marc Chagall is roughly the size of a standard sheet of office paper. When it was stolen in ’96, Gordon Gallery owner Shaya Yariv speculated that it may have been smuggled out under someone’s raincoat.

“I think the painting is eating oysters in Paris or Moscow by now,” Yariv told the media at the time.

(The current gallery owner, Amon Yariv, said the incident was the only theft ever at the Gordon, which in 1975 held the first art auction in Israel.)

It’s unclear whether “Jacob’s Ladder” ever made it to France or Russia, but it was ultimately found in Jerusalem in 2015. When an elderly woman died in the city that year, she bequeathed the painting — never hung, and always stored in her vault — to her nephew.

“Nobody knew anything about this painting, even close family members,” said Amitai Hazan Tiroche, a third-generation auctioneer at the family-run auction house. “When [the nephew] came to claim it — on the one hand, it was a dream scenario because he inherited something that could be very valuable.”

The nephew approached a local art dealer who informed him that the work was likely a Chagall but he would need confirmation from Comité Marc Chagall, the organization founded by the Russian-French artist’s heirs to determine the authenticity of art attributed to Chagall. When the nephew approached the group, it immediately recognized the work as stolen and contacted the authorities.

Migdal Insurance, which paid the 1996 claim on the stolen Chagall, demanded custody of the painting and a court case ensued. A Tel Aviv court ruled in 2015 that the painting be transferred to Migdal following a precedent set by a 2003 Israeli Supreme Court decision. The High Court returned two stolen paintings bought in good faith at a Tel Aviv flea market to the U.S. government, which had paid an insurance claim on them after they disappeared in transit from New York to Tel Aviv.

“There aren’t a lot of cases like this,” Tiroche said. “It’s definitely one of the few cases in the Israeli art world.”

Migdal is now offering the work for sale to recoup the money it paid to the painting’s previous owner. The company’s desire to close the case likely explains the relatively modest projection for the painting of $130,000 to $180,000, nearly identical to what Gordon estimated as its worth 24 years ago.

The estimate doesn’t reflect the increase in value of Chagall works over the past two decades. Though sale prices vary according to the period of an artist’s career, subject matter and ownership history, among other variables, Chagall’s “Les Amoureux” sold at Sotheby’s in New York in 2017 for $28.45 million — a record for the artist.

“If we were to follow absolute values, then Chagall’s prices have almost doubled over the past 20 years,” Tiroche said. “We want the opening price here to be relatively attractive to buyers in Israel and overseas because if the estimate is too high, people may decide not to bid. And also the insurance company wants to finish the saga of the money they paid out over 20 years ago.”

The opening bid at the auction, taking place this Saturday evening, has been set at $110,000.

Prospective bidders will have to figure out the provenance of “Jacob’s Ladder” for themselves. Though the general practice is to publicize the full provenance of art offered for sale, in part to prevent stolen works from circulating on the open market, the Tiroche catalog does not contain such information for the Chagall — information Tiroche described as “gossip-oriented” and unsuitable for inclusion in the catalog.

Besides, Tiroche said, everyone knows the story anyway. His principal concern is just ensuring the painting stays in the showroom long enough to make it to the auction block.

“The painting isn’t big, but now it’s also in a heavy, big frame,” Tiroche said. “This place is secured. Touch wood, in 27 years we haven’t had a single incident of theft or anything like that. Everything should be OK.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.