(JTA) – Eric Zemmour, one of the most famous pundits in France — or infamous, depending on who you ask — headlined a political convention in Paris last month titled the “Convention of the Right.” Joining Zemmour was Marion Marechal, a rising star of the French far right and the granddaughter of National Front party founder Jean-Marine Le Pen.

Zemmour, 61, a birdlike man who stands 5-foot-4, delivered a thrilling performance to his fans despite a bout of laryngitis.

“Our brilliant progressives, so arrogant, so enamored with the future and dismissive of past things like their previous iPhone, believed they had left the archaic reality of war of nations and classes. They’ve landed us in a war of race and religions,” Zemmour said at the podium, pausing for passionate applause.

“We’re caught between the anvil and the hammer of two universalisms crushing our nation, people, territory, traditions, ways of life and culture,” he warned. “Mercantile universalism that’s served to transform our minds into rootless zombies in the name of human rights. And Islamic universalism feeding on our religion of human rights to safeguard its occupation, colonization, seizure of French territory and slow application, thanks to numerical strength, of religious laws on foreign enclaves.”

The speech highlighted three things: Zemmour’s anti-Muslim views, his ever-rising popularity among the right-wing base in France, and the intellectual and historical nature of his arguments. He is a unicorn in his country in the sense that he espouses such conservative views from inside its predominantly left-wing academic and political elite.

What Zemmour did not outright mention was his Jewish identity, something he proudly defends, and which is used to both defend and critique him in the public sphere. Zemmour, the son of Sephardic immigrants from Algeria, mentions his Jewishness often in fiery debates. He uses it to deflect accusations of racism and cite the French Jewish experience in France, including his own, both as a model for other religious minorities and immigrants and as evidence that French Muslims, in his view, have failed to follow that example.

Zemmour has become a household name in his native France because of the controversies surrounding him. He was convicted of public hate speech and fined twice, first for calling Muslims “invaders” in 2011 and again for saying in 2016 that most drug dealers are Arab or African.

Marion Marechal delivers a speech at the “Convention of the Right” in Paris, Sept. 28, 2019. (Daniel Pier/NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Earlier this month, Zemmour was at the center of a polarizing debate after becoming a regular panelist on a talk show aired by the privately owned CNews television channel. Citing his hate speech convictions, his critics want him off the air.

Soon after, he prompted another avalanche of condemnations over his statement backing Thomas Bugeaud, a colonial general from the 18th century whom Zemmour said “massacred” Muslims and some Jews in Algeria.

“Well, I’m today on the side of General Bugeaud,” Zemmour said on air. “That’s being French.”

Alain Jakubowicz, the president of the Jewish LICRA anti-racism group, said Zemmour “dreams about massacring” and should go to a “psychiatric hospital.”

Zemmour later explained that he did not support massacres, but merely cited his own support for Bugeaud as an example of how Frenchmen should identify with their country’s interests over those of any other community or ethnicity.

Nonetheless, the prominent French historian Alexis Levrier argued in an interview this month that Zemmour should not be allowed to express himself on national media because “he’s no longer a journalist.”

“He feeds lies, he spreads insults and slurs about Islam,” Levrier said. “You can’t invite him as a journalist, he’s a polemicist focused on identity politics” who is “therefore extremely dangerous.”

Gilles-William Goldnadel, a friend of Zemmour and former member of the executive board of the CRIF umbrella group of French Jews, said fellow intellectuals resent Zemmour “because he is flesh of their flesh, he’s not an outsider.”

“Whatever you think about what he says – and I think he often gives ammunition to his enemies by not choosing his words carefully — there’s no denying he’s a courageous thinker,” Goldnadel said.

Zemmour seems poised to launch a political career based on his appeal to the far-right population, which is more impressed than put off by his fulminations against Muslims, especially because they differ from the rhetoric of many politicians — even the contemporary National Front leader, Marine Le Pen. In 2017, Le Pen called multiculturalism “the soft weapon of Islamic fundamentalists” and won about a third of the vote in the final round of that year’s presidential election.

In a 2015 survey, 12 percent of the respondents said they would vote for Zemmour if he ran for president. Nearly five years and hundreds of television appearances later, he has remained vague on the issue (Zemmour and his publisher did not respond to multiple requests to be interviewed by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on this and other topics).

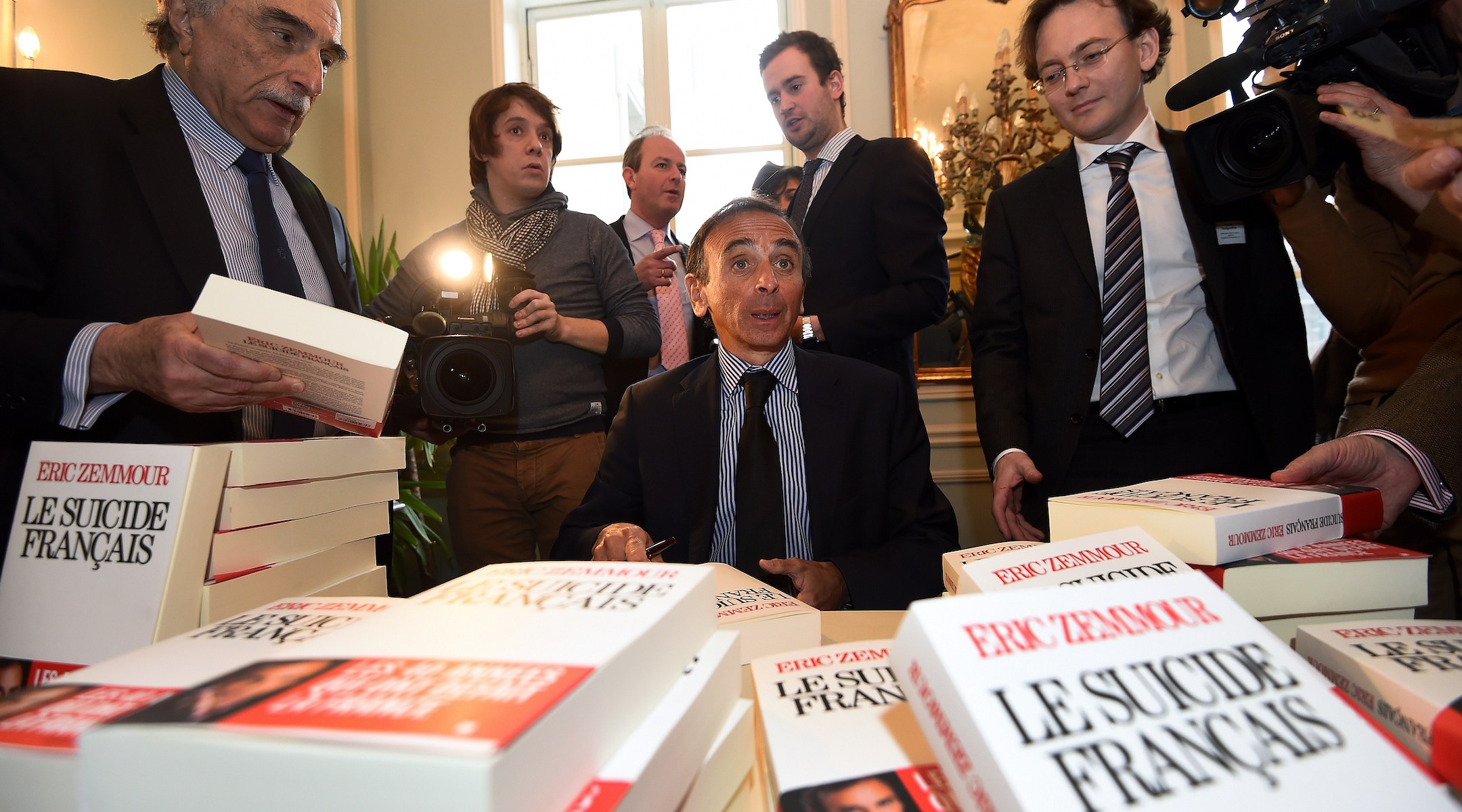

Eric Zemmour signs copies of his book “The French Suicide” at a business club in Brussels, Belgium, Jan. 6, 2015. (Emmanuel Dunand/AFP via Getty Images)

Zemmour was not always conservative. Born in 1958 and brought up as “a French Jew of Berber origin,” Zemmour had considered himself left-wing and voted Socialist throughout the 1970s and ’80s while working as a copywriter for a publicity agency. He received a bachelor’s degree in political science and began working as a journalist for Le Figaro after his stint in publicity.

He once supported the lenient immigration policies of former president Francois Mitterrand.

“The French assimilationist model is demanding,” Zemmour said in a recent interview about his Jewish identity.

“Nothing to the Jews as a people, everything to them as individual,” he added, paraphrasing the words of Stanislas de Clermont-Tonnerre, an 18th-century French politician who supported lifting restrictions on French Jews. “Like it or not, that’s how it is. French Jews adopted it enthusiastically.”

Zemmour’s Jewish name, the one he uses when he attends synagogue in Paris on the High Holidays, is Moises, according to Goldnadel, a well-known lawyer whose views are right of center.

Many French Jews who feel victimized and helpless at the face of Islamist violence “appreciate what Zemmour is saying about Islam,” Goldnadel said. In a 2014 poll among hundreds of French Jews, 13.5 percent of the respondents said they support Marine Le Pen.

But few French Jews — least of all Goldnadel — accept Zemmour’s defense of the Holocaust-era record of the pro-Nazi Vichy government, which was responsible for rounding up and transporting countless Jews to be murdered. Zemmour argues that Vichy sacrificed foreign Jews living in France in order to save Jews with a French passport.

“There was, effectively, a pact with the devil in which Vichy gave up foreign Jews, or at any rate allowed them to be taken, in order to save French Jews,” Zemmour said during a 2016 debate with a former chief rabbi at the Grand Synagogue of Paris.

His thesis is both based on and supported by research by the renowned historian Alain Michel, but contested by others, including Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, who called Zemmour’s interpretation “completely false.” Francis Kalifat, the CRIF president, condemned the synagogue for even hosting Zemmour over the issue.

Far-right demonstrators hold banners reading “Nation” and ”Against Islamo-Leftist Fascism” as they gather to show support for Zemmour prior to his arrival at a book-signing session in Brussels, Jan. 6, 2015. (Emmanuel Dunand/AFP via Getty Images)

Goldnadel says he “must strongly but respectively disagree with Eric on this point,” citing several actions in which French collaborationist authorities offered up French and foreign Jews without even being prompted by the Nazis.

Regardless of its accuracy, Zemmour’s historical thesis and tough talk on Islam are popular with many Frenchmen precisely because it is a Jew who is arguing these points, according to Dominique Moisi, a French-Jewish political scientist.

“The classic, conservative bourgeoisie can say to themselves, this is a good Jew: He says that Vichy wasn’t so bad, and that Muslims are even worse than people say usually,” she told The Washington Post in an interview for an article about Zemmour.

To Shmuel Trigano, a French-Jewish author who has written extensively about anti-Semitism, Zemmour’s rise to prominence is a backlash against a censorial media and judiciary that has stifled public debate in France.

“The fact that he’s Jewish makes it more difficult to dismiss what he’s saying,” said Trigano, who is well-known in France for chronicling how the French government and media imposed a media blackout in the 2000s on hundreds of anti-Semitic attacks by Arabs in order to “not pour oil on the fire” of anti-Arab sentiment, as then interior minister Daniel Vaillant later explained.

Trigano said he doesn’t agree with Zemmour’s “radical opinions,” but he understands the phenomenon surrounding him.

“When you block any avenue for expressing these views rather than debate them, they have a way of become unstoppable,” Trigano said. “This is what’s happening right now with Eric Zemmour.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.