(JTA) — Mad magazine is on life support, and I can’t say I’m either surprised or all that sad about it. DC Entertainment announced last week that the satirical magazine will stop publishing new content. It was like hearing about a beloved old relative who passed away: I hadn’t had any meaningful contact in years, but had fond memories of when we were still close.

For me, that meant during my pre-bar-mitzvah years, growing up in the 1970s. For a suburban kid binging on a diet of Saturday morning cartoons and grim, adults-only dispatches on the nightly news, Mad was a hoot — hilarious, irreverent, slightly risqué.

Today I am a man, and realize Mad was something more.

Many of the eulogies have focused on the political legacy of the magazine. The Denver Post once celebrated its “mid-20th-century history of bold political satire and anti-censorship court cases.” (In 1964 the Supreme Court refused to hear music publishers’ complaints over the magazine’s right to publish song parodies.) Others suggested that its mocking attitude influenced the ’60s generation to “question authority.” The Washington Post called it the “most influential magazine of the post-World War II era.”

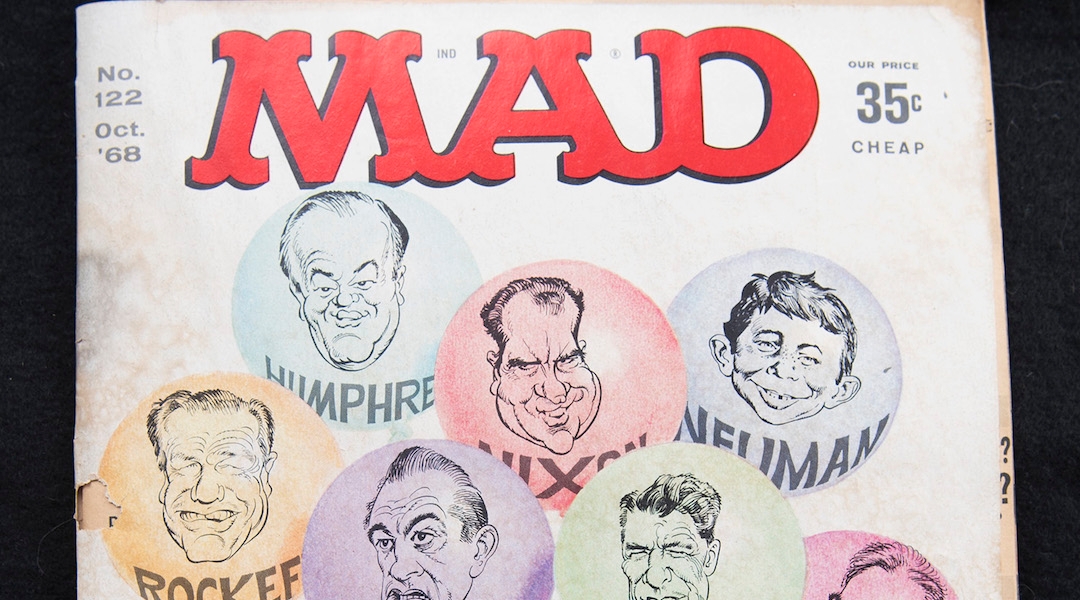

Looking back on the old issues, I’m also struck by how political they were, with biting parodies of the 1960s “Establishment” represented by Richard Nixon, George McGovern and Henry Kissinger. An American flag poster from 1971 would still raise eyebrows today, reworking the pledge of allegiance into a bitterly ironic statement on American divisions, addressed to “one nation under God with liberty and justice for all, including kikes, wops, spics, niggers, WASPS, etc.”

Watergate, the Vietnam war, the “generation gap,” the civil rights movement: Mad translated the issues dominating the news of the day and the whispered conversations of my parents and their friends into a comic language we kids could understand.

But I barely remember the political stuff. It is the education Mad gave me as a consumer — and consumer of pop culture — that sticks with me. In a pre-ironic age, when advertising had insinuated itself into seemingly every corner of our lives (or so we thought, in the era before smartphones), Mad taught its young readers to be wary of corporate America. Its fake ads undermined health claims for cigarettes and the promises of cosmetics. An advertisement for “Sucka” instant coffee forced us to acknowledge the workers who were exploited so that our parents could enjoy “instant” satisfaction. Mad was in the “deconstruction” business years before the term was coined. It was Consumer Reports for kids.

Mad worked the same subversive magic on TV shows and feature films, in the classic parodies written by Dick DeBartolo and Larry Siegel and drawn by Angelo Torres and Mort Drucker. “The Oddfather” parody asked if Marlon Brando was really a believable Mafia don with his cheeks stuffed with cotton. If the Chinese immigrant hero of the TV series “Kung Fu” is such a pacifist, why does he end up whuppin’ cowboy ass at the end of every episode? And how come the newsroom crew on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” never seemed to cover a news story?

Later I would discover Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, whose movie criticism gave me a vocabulary and methodology for understanding why a piece of art works or doesn’t. Mad was there first, in a visual language that we absorbed by osmosis. It said, ” I can enjoy this movie, but I can also see how absurd, artificial and manipulative it is — and how it fails on its own terms.”

We Jews like to claim this critical distancing as something distinctly Jewish — or at least a trait perfected by Jews in the mid-20th century. The case can be made: The “usual gang of idiots” who put Mad together included founders William Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman, editor Al Feldstein, and artists and writers from Drucker, Al Jaffee and Dave Berg to Larry Siegel, Stan Hart and, more recently, Drew Friedman, all Jews. (And all men, I know — the topic for another essay.) Its prose dripped with Yiddishisms, some real (shmuck!) and some imagined (furshlugginer!).

Nathan Abrams, in an article on Mad’s Jewish sensibility in the journal Studies in American Humor, argues that in the 1950s and ’60s Mad “marinated in the same urban Jewish culture” that produced the New York Intellectuals. No surprise, then, that its contributors had the same intellectual concerns of their counterparts in academia and high-brow literary magazines: “suburbia, psychoanalysis, existentialism, Freudianism, intellectual pretension, bohemianism, technology, disarmament, and containment.”

Mad’s contributors were the low-brows in this media class war. Jews and other sons of immigrants at the top rungs of the entertainment food chain — the movie makers, ad execs, book publishers and publicists — were being harassed by more Jews and other sons of immigrants from the bottom-feeding world of comic books and humor rags.

This class conflict reached its peak in the 1973 parody of “Fiddler on the Roof,” titled “Antenna on the Roof.” Drucker and writer Frank Jacobs set the musical in a tinseled, clearly Jewish suburb, and changed the Sholem Aleichem adaptation into an angry indictment of Jewish assimilation.

Zero Mostel is portrayed as “Mr. Buckchaser,” and his daughters are Sheila, “A Free Sex fanatic”; Nancy, a “speed freak just now,” and Joy, who “Makes bombs in the attic/And answers the phone with Quotations from Mao.” Their world is soaked in bourgeois excess, and their existence is corrupt and soulless. The last page is a cartoon jeremiad, with a crowd of shtetl peasants led by Chaim Topol as Tevye condemning the nouveaux riches for all the tsurris of the 1960s, from student unrest to pollution to striking unions.

“Now that we’ve seen the Mess you’ve made,” they sing to the tune of “Miracle of Miracles,” “We’re afraid God wants back his melting pot!” It’s an entire Philip Roth novel in a seven-page comic.

I stopped reading Mad regularly in the mid-1970s, the magazine having done its job on me, and pop culture. I was ready for the raunchier, more tasteless fare of “National Lampoon,” and the not-ready-for-prime-time satire of “Saturday Night Live,” where Mad’s influence was obvious whenever a fake commercial came on selling flammable toy cars or “Little Chocolate Donuts” breakfast cereal.

But whenever I talk back at an implausible movie or TV show, or tweet a devastating take down of a disingenuous politician, I remember my old friend Mad.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.