This story originally appeared on Alma.

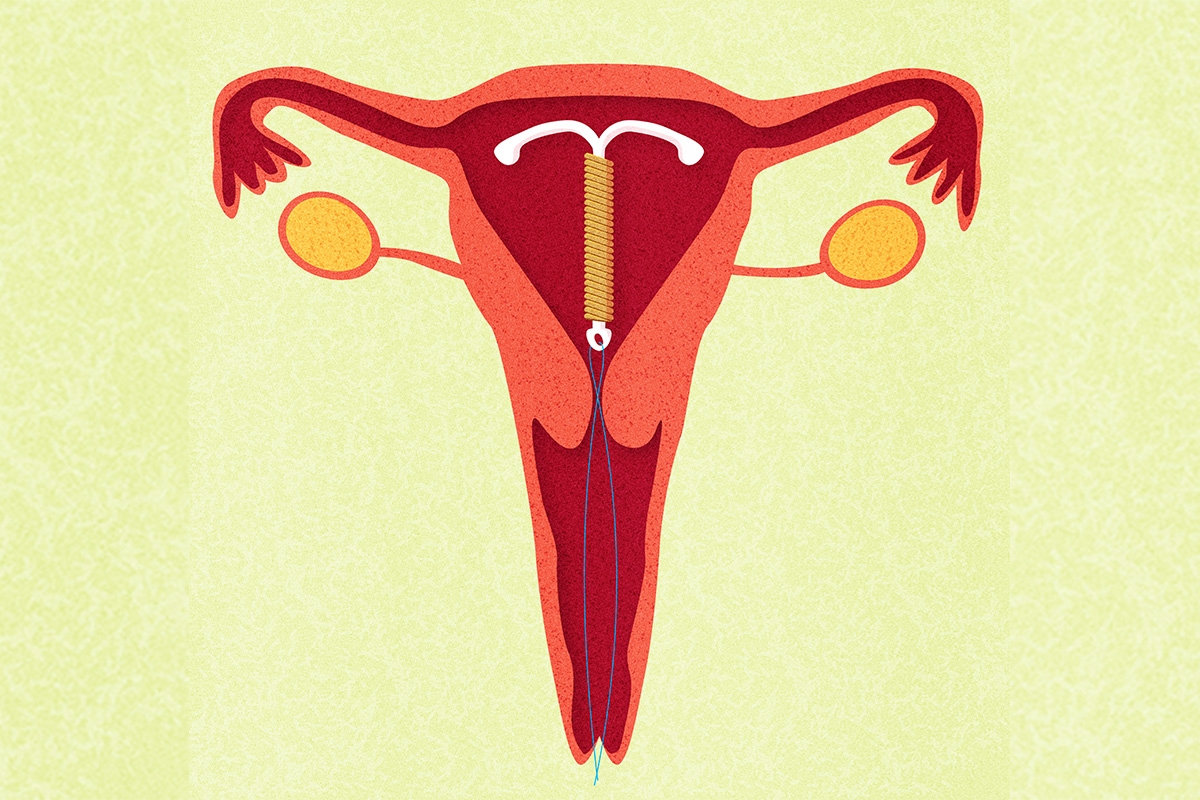

When most people ask me if I’ll ever have children, I’m usually pretty blunt. Nope, kids are absolutely not happening. Ever. The only thing occupying my womb will be my IUD.

But when it comes to people at my synagogue, I’m typically a little more evasive. I’ll talk about how I’m focused on moving and going to graduate school before getting married and having children.

I’m up front and open about almost everything else in my life with members of the local Jewish community, including more controversial topics like politics. Why am I so reticent to be honest about not wanting to have children?

There’s a tremendous amount of pressure on Jewish women to have children, both from a liturgical and societal perspective. Every week we recite a prayer for the congregation asking to be blessed with “healthy children devoted to Torah.” Some of the most important rituals in our culture, including the brit milah (bris), simchat bat (baby naming ceremony), and bar and bat mitzvahs center around children. Then there’s the concern that non-Orthodox Jews in the U.S. aren’t having “enough” children, that the Jewish population will decline and even racist conspiracies around a Palestinian “demographic threat” that endangers Israeli sovereignty.

There are many legitimate concerns about ensuring future generations remain connected to Judaism. But why are we blaming non-Orthodox women for not having “enough” children instead of low wages, the high cost of childcare, workplace hostility to mothers, high synagogue dues, lack of relevant and accessible programming for working families, insufficient Jewish education programs or lack of support for Jewish people of color and LGBTQ families?

It’s easy to blame women for the community’s demographic worries. It’s much harder to work on fixing the many obstacles that make having children untenable, or make it hard for families to participate in Jewish life.

But even if we had a supportive and functioning system for families, there are still going to be people like me who don’t have children because we just don’t want kids.

In preparation for my beit din, or rabbinical court, I had to write about my commitment to keeping a Jewish household, and in the future raising my children to be Jewish. Writing about this was even more challenging than writing about how I had challenges relating to the State of Israel. I chose my words carefully, stating that having children wasn’t a priority, but that I’d absolutely raise any hypothetical children to be Jewish. I also cited some health concerns that would make pregnancy and birth extremely challenging. I had in-depth conversations with my partner to make sure we were on the same page. I was afraid that the beit din would consider my answers insufficient and spike my entire conversion. Fortunately it wasn’t even brought up.

Misogynistic concern-trolling in Jewish communities takes many forms. Non-Orthodox women face scrutiny for not having enough children, and Orthodox women face scrutiny for having too many. In the game of patriarchy, all women lose. Instead of pointing fingers at each other, why can’t we support all Jewish women and their families, no matter what their families look like?

In the aftermath of multiple states passing extreme restrictions on abortion, Jewish women have been pointing out that Jewish law allows for considerably more gray area on abortion than current Republican policy. In fact, whether or not women are exempt from the mitzvah to have children has historically been a subject of rigorous rabbinical debate, with a spectrum of opinions on the issue.

Let’s also not forget that historically it’s been a bunch of men, who could not get pregnant and did not shoulder the many burdens of parenting making decisions about how Jewish laws regarding pregnancy and parenting applied to women. In fact, it was due to the tireless advocacy of many Jewish women, including Emma Goldman, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shulamith Firestone, who were active in the movements that gave women greater reproductive autonomy today.

I just wish people could recognize that there are many ways to do “l’dor v’dor,” from generation to generation, that don’t involve having children, and that Jewish women who don’t want to have children aren’t any less dedicated to making sure our Jewish communities thrive for future generations to come.

I have taught children, hosted Shabbat dinners, helped friends celebrate holidays, written about ways to create a meaningful Jewish life, and given advice and support to people during their conversion journeys. One of the greatest strengths of the Jewish community is our creativity and resilience, and child-free Jews like myself are showing that there are many ways to address the challenges our community faces without compromising our own values and desires.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.