NEW YORK (JTA) — In the 1930s, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler both traveled to Scotland for medical school because, they said, American universities wouldn’t admit them as Jews.

Eighty years later, academic and cultural institutions the world over are deciding whether to reject the Sackler brothers’ children — not because of their religion but because of their actions.

Mortimer and Raymond Sackler are the late patriarchs of a family under fire now for its central role in the opioid addiction crisis, which has led to hundreds of thousands of American deaths. The brothers’ giant pharmaceutical company, Purdue Pharma, is the manufacturer of OxyContin, one of the leading opioids on the market.

Mortimer died in 2010 and Raymond in 2017. Now their widows, along with five of their children and one grandchild, are being sued by three states for allegedly committing a range of fraudulent and deceptive practices in the marketing of OxyContin. Purdue reached a $270 million settlement with the state of Oklahoma in March.

Before becoming notorious for painkillers, the Sacklers were noted for their philanthropy. So a range of museums and schools are grappling with what to do with the wings, schools and chairs named for them. A couple of Jewish institutions, including Tel Aviv University, face that dilemma as well.

(A third Sackler brother, Arthur, died in 1987, when his brothers bought out his shares — nine years before OxyContin was introduced in 1996. Arthur’s family, which has also given philanthropically, has distanced itself from OxyContin.)

The Sackler brothers were born to Jewish immigrants from Poland and Ukraine.

Arthur Sackler, the oldest, was born in 1913 to Jewish immigrant grocers in Brooklyn. Mortimer and Raymond were born, respectively, in 1916 and 1920. The brothers became psychiatrists: Arthur earned his degree at New York University, the others attended medical school in Scotland.

Arthur lived in Manhattan, Mortimer in London and Switzerland, and Raymond in Greenwich, Connecticut.

They turned a small pharmaceutical company into an empire.

In 1952, the brothers bought Purdue-Frederick, a small New York City drug company, which later became Purdue Pharma. At the time it produced laxatives.

But everything changed in 1996 when the company began to market OxyContin, a prescription painkiller. The drug was marketed as safer than alternatives because of its so-called controlled release, which gradually released the drug into the patient’s bloodstream rather than doing so all at once.

According to a 2017 feature on the family in the New Yorker, the Food and Drug Administration said the drug was less prone to addiction than alternatives because of the controlled release. That was despite Purdue declining to do any clinical studies on the drug’s addictiveness, according to the New Yorker.

OxyContin was prescribed broadly for a wide spectrum of pain, and has made the Sacklers America’s 19th richest family with a combined net worth of $13 billion, according to Forbes. As recently as last year, eight Sacklers sat on Purdue’s board.

But recently, as the human toll of the addiction crisis has become evident — in large part, investigators complain, because the dangers of addiction to OxyContin were downplayed or kept hidden — the Sackler name has become synonymous with controversy. Now the number of Sacklers on the board is zero.

Now they are being sued for aggressively and deceptively marketing an addictive drug.

Lawsuits in New York, Massachusetts and Connecticut charge that the Sacklers dispatched an army of marketers to portray OxyContin as a safe pain treatment despite knowing of its addictive potential.

“The basis for this reduced abuse liability claim was entirely theoretical and not based on any actual research, data, or empirical scientific support, and the FDA ultimately pulled this language from OxyContin’s label in 2001,” states the complaint from New York state filed in March. “Nonetheless … Purdue made reduced risk of addiction and abuse the cornerstone of its marketing efforts.”

The litigation, as well as reporting on the issue, has shown that Richard Sackler, Purdue’s former president, sought to shift blame to addicts for the growing addiction crisis. In an email sent in 2001, he wrote that “we have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible. They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

The New Yorker, as well as other detailed articles on Purdue and the addiction crisis, has found evidence that the company engaged in a variety of misleading practices. Purdue allegedly misled doctors about the drug’s addictive potential and recommended dosage, encouraging doctors to prescribe OxyContin when it was not needed.

“He told the company we are going to measure our performance by prescription by strength, giving higher measures to higher strength,” said Barry Meier, author of the book “Pain Killer,” regarding Richard Sackler, on The New York Times podcast The Daily. “This was a family that … was not only counting every pill that was being sold but making sure that every pill that was sold was the highest strength of that pill because it would bring in the highest amount of dollars.”

In addition to Richard Sackler, the suits name his father Raymond’s widow, Beverley, his brother Jonathan and son David, who all served on the board. The suits also name Mortimer Sackler’s widow, Theresa, his daughters Kathe and Ilene, and his son Mortimer David Alfons Sackler. Those three children served on Purdue’s board.

And some beneficiaries are rejecting their donations.

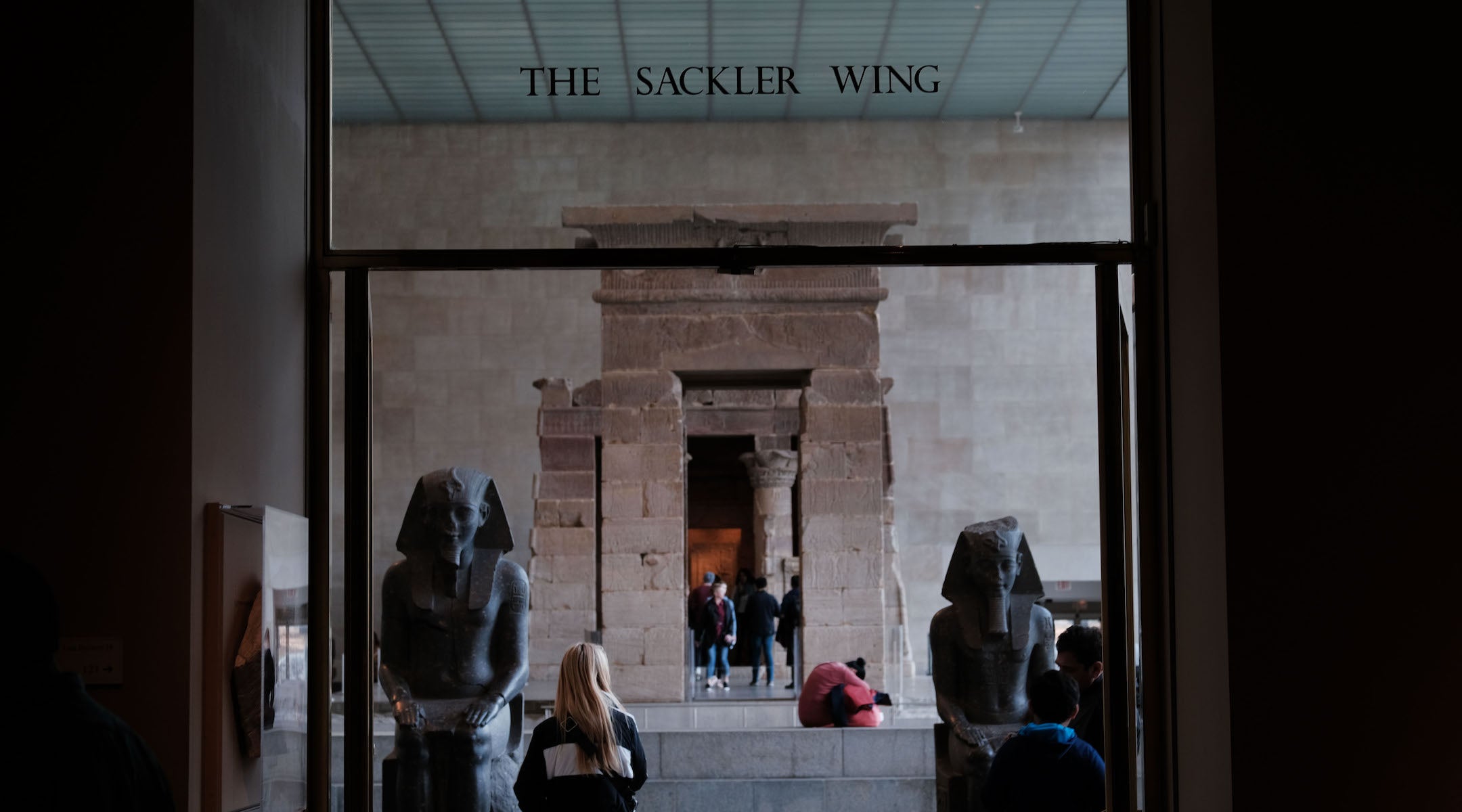

The Sackler family has used its wealth to fund education, research and the arts. Family members have donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Tate Modern in London and the Louvre in Paris. They have funded institutes at Columbia and Yale universities, among others.

And in the Jewish world, there’s the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University and dozens of other Sackler divisions at the school, as well as the Sackler Staircase at the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Some of the institutions that have accepted Sackler largess said they will no longer do so, including the Berlin museum, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Tate. The National Portrait Gallery in London, together with the family, canceled a planned donation this year.

But Tel Aviv University said that for now, it will not be changing the medical school’s name — nor those of more than 30 entities at the school named after the family. As recently as 2013, Israel’s United Nations ambassador honored the Sacklers for their support of Tel Aviv University.

“Sackler is nothing short of a brand name at Tel Aviv University,” then-university President Joseph Klafter said, according to a news release. “Practically every step you take on campus will lead you to a Sackler-supported unit.”

Will that change now? According to a spokeswoman, the donation was made to the medical school 50 years ago. As for the others, the university is going to wait and see. Institutions rarely have the mechanism to return gifts already spent, but some have clauses saying that donors’ names can be removed if the money was “derived illegally or through a socially unacceptable manner.”

“The Sackler family donated 50 years ago to establish the medical school,” she wrote in an email. “The subject has yet to be resolved in American court.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.