For years, a newspaper with a foreign name would arrive weekly at my family’s home in Buffalo. I didn’t pay much attention to Aufbau — it was my father’s — but that changed when I started high school and enrolled in freshman German.

Dad, who was born in Berlin and escaped the Nazis with his mother and stepfather in March 1938, had tried to teach Mom and me and my two sisters some basics of his Muttersprache, his mother tongue, setting up a small blackboard in our kitchen, drilling us in some introductory nouns and verbs and simple sentences.

It only stuck with me. By high school I decided to formally study German.

Aufbau became a tool. I perused it to increase my growing vocabulary auf Deutsch. And, as a byproduct, to boost my knowledge of German history and German-Jewish culture. I ended up taking German for eight years in high school and college.

Count me as an Aufbau — it means “reconstruction” — success story.

The paper, a lifeline for generations of German-speaking Jewish immigrants in the United States, was founded in 1934 — the year after Hitler rose to power and prescient Jews began leaving their heimat (homeland) — by the German-Jewish Club. (It eventually became the New World Club, to sound less provincial.)

Most of Aufbau’s readers, refugees who had escaped before the Final Solution, and survivors who later came out of the death camps alive, were in Washington Heights, where the bulk of émigrés from Germany and Austria ended up settling.

The paper served the role, as newspapers geared to the needs of immigrants typically do, of language instructor, acculturation guide, surrogate parent, arranger of reunions, lister of community events, interpreter of political happenings, source of ads for European-type spas and German-speaking businesses, and, of course, trusted source of news.

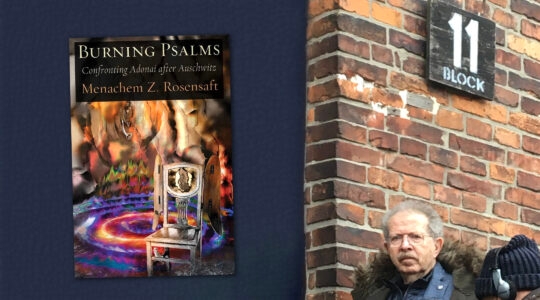

In the new book “The World of Aufbau: Hitler’s Refugees in America” (University of Wisconsin Press), with a black-and-white photograph of Albert Einstein raising his right hand at a citizenship swearing-in ceremony on the cover, Peter Schrag chronicles the Aufbau’s story.

Originally designed to bind the immigrants who were adjusting to life here and to apprise them of developments in the countries they left behind, Aufbau reported on the murderous excesses of the Third Reich; on battles and civilian deaths in World War II; on the exploits of Allied Jewish soldiers; on the search for disappeared loved ones in the aftermath of the Holocaust; on the successes of transplanted German-speaking Jews in the U.S.; and later on Israeli wars and other news in the Jewish state.

Aufbau reported on the horrors of the Shoah, earlier and in greater detail, than most U.S. newspapers did.

For Schrag, a California-based writer and prolific author, the book is personal; he came to the U.S. with his parents from Germany at 11 in 1941.

For me, the book is also personal.

Dad was 17 when he arrived in the U.S., knowing little English. (His step-father, once a prominent physician in Berlin, worked as a cancer surgeon at Buffalo’s Roswell Park Cancer Institute; Dad’s birth father died after being deported “to the East.”)

Typical of immigrants who adapted to American ways, Dad changed his name — from the Teutonic-sounding Claus Peter to Peter; the Lippmann to Lipman. But he, according to my U.S.-born friends, never lost his accent; I never detected it.

Like many immigrants from Germany and Austria, Dad found his new surroundings devoid of his accustomed, superior Kultur, which he declared, to the annoyance of proud Buffalonians.

One day he made such a dismissive remark to one Helene Finkelstein at a USO dance. His insufferable comments brought a spirited rejoinder, a defense of Buffalo, from his dance partner; their marriage lasted nearly 60 years, till Dad died in 2005.

Like many Jewish refugees, he wore the uniform of the U.S. Army. Drafted in 1941, still not a U.S. citizen, he served briefly at Fort Bragg, N.C., until he earned a commanding officer’s ire for sticking up for a black soldier who had come under attack by white racist G.I.s. After seeing — and fleeing — discrimination in his homeland, Dad wouldn’t stand by when a member of another minority group was mistreated.

Schrag’s book doesn’t tell Dad’s story; for decades a salesman and bill collector, he became a loyal citizen and loving father, but did not lead a notable life. Dozens of other stories are in the book, though — those of Henry Kissinger, Dr. Ruth Westheimer and Einstein. They, or their families, were Aufbau readers.

The paper was for me a formal entry into the German language and the German Weltanschauung (worldview). I don’t know what Dad got out of it. I don’t remember him reading it or discussing the contents with me; he merely passed it to my eager hands. In retrospect, it’s unusual that Dad subscribed to Aufbau. Raised in an extremely assimilated Jewish family in Berlin, he had little connection to things Jewish.

For most readers, struggling with a new culture, Aufbau was indispensable, following in the footsteps of other émigré-oriented papers. (Aufbau was taken over by a Swiss publishing firm in 2004 and is now a monthly, glossy magazine.) For earlier Jewish immigrants, the Ostjuden, Yiddish newspapers, like the legendary Forverts, played that role. Mom’s Orthodox parents, from a shtetl in today’s Belarus, each week read a Yiddish-language newspaper.

Both papers became victims of their own success in helping to make their readers into “good Americans,” fluent in English.

Now, when I pass the newsstands of Forest Hills, where I — and thousands of émigrés from Uzbekistan — live, I find many newspapers in Russian. The Bukharian seniors in my apartment building, sitting hours outside on benches schmoozing in Russian, favor these papers over The Times or the tabloids.

Readers of the Aufbau would understand.

steve@jewishweek.org

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.