This article originally appeared on Kveller.

If you take a look at bookstore shelves and best-seller lists, it seems that readers continue to seek out stories about the Holocaust. This is in no way a bad thing — more people should learn about the Holocaust, not fewer.

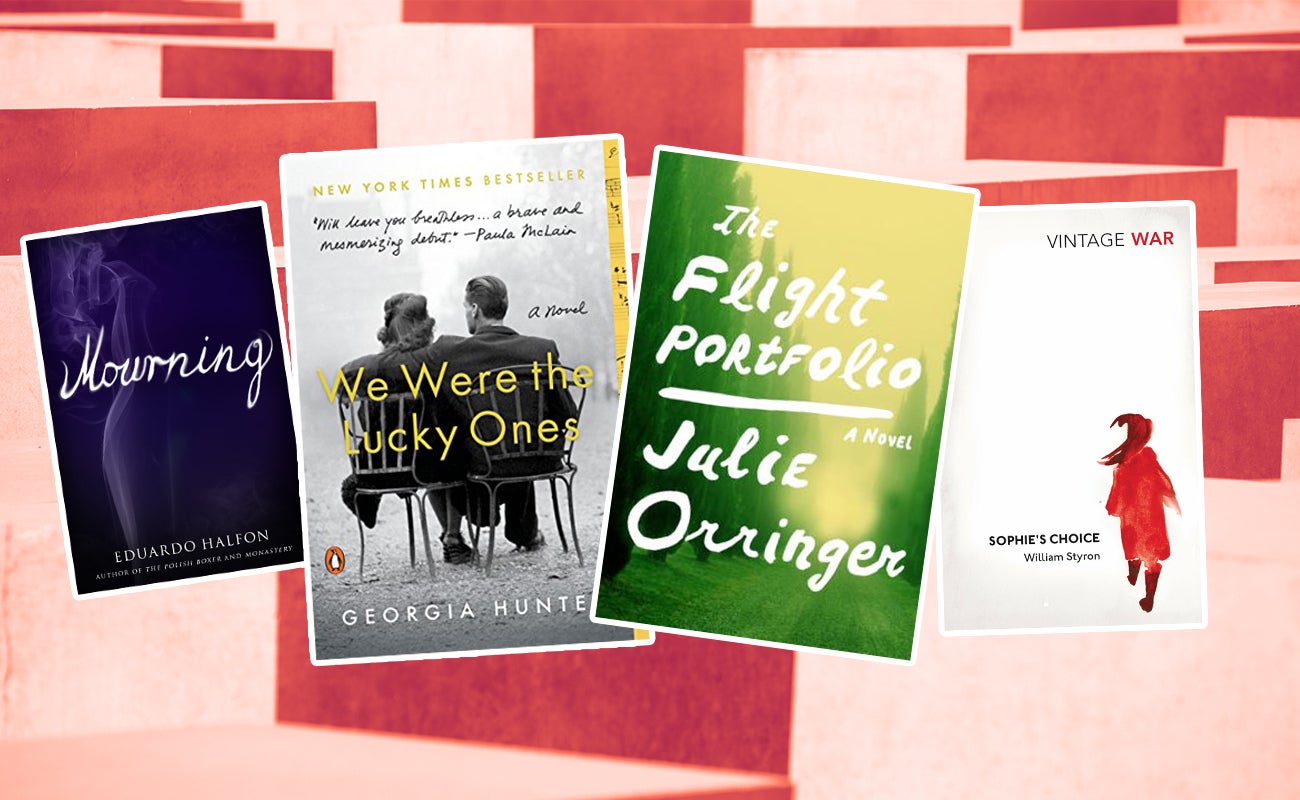

Among recent buzzy Holocaust novels are Julie Orringer’s “The Flight Portfolio” (May 2019), which tells the tale of Varian Fry, who helped thousands of Jews flee occupied Europe and became the first American to be named Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum. Georgia Hunter’s “We Were the Lucky Ones” (2017) is the fictionalized story of the author’s Polish Jewish family surviving against all odds. Similarly, Eduard Halfon’s “Mourning” (2018) is an autobiographical novel translated from Spanish that dives into the legacies of the Holocaust based on Halfon’s family.

These books are all undoubtedly worth reading. And yet, is it just me, or does it feel weird that the Holocaust remains so popular? Why do readers continue to seek out stories of the most traumatic event of the 20th century? How are 19 of the top 20 best-sellers in Jewish literature and fiction on Amazon all Holocaust fiction?

With more questions than answers, I set out to understand why readers in 2019 keep Holocaust stories — which I define loosely as either works of historical fiction set during the Holocaust or that deal with the legacies of the Holocaust — at the top of the charts. I came to understand that Holocaust fiction remains popular for four key reasons: a mix of who is telling the story (the third and fourth generations), the types of stories (not straightforward, but morally ambiguous), the historical truth at the heart of all these novels and our current political moment.

Let’s dive in.

Once you start seeking out Holocaust fiction, you see it everywhere.

However, as Jewish Book Council editorial director Becca Kantor explained, the amount of Holocaust fiction books that are being published are “not necessarily increasing, but it’s certainly not decreasing, either — which, as more time passes since the Holocaust, in itself seems quite significant.”

“Although we’re moving further away from the Holocaust, we only find out more about it as time goes on,” Kantor said. “As writers from the third and fourth generations after the Holocaust begin to address this history in fiction, they often look at it more dispassionately than previous generations.”

Author Georgia Hunter echoes this sentiment. As the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor — she didn’t discover this until after her grandfather died — she set out to research her family’s history, which she eventually turned into the best-selling novel “We Were the Lucky Ones.” In an interview with Kveller, Hunter explains that as a third-generation survivor, she feels like there is an influx of stories being told now.

“Second-generation [survivors] were born right after the war ended, and everything was still so raw,” she said. “A lot of times, that generation was protected, and these stories were not shared; these kids were cocooned, in way, from the experiences that their parents had endured. Being one generation removed from that gives us — as grandchildren of some of these survivors — a little bit more freedom to ask the questions that maybe our parents never felt comfortable asking. And along with that, those survivors maybe are a little bit more willing to share as they get older.”

That last point is key: The number of Holocaust survivors who are still with us is shrinking. So there’s a push by their relatives, and by writers, to document their stories before it’s too late.

Holocaust fiction that remains popular is more nuanced than portraying “Jews as good” and “Nazis as bad.” Rather they paint complex pictures of deeply conflicted individuals.

Varian Fry, the protagonist of Orringer’s “The Flight Portfolio,” has to decide who is worth saving. Fry is sent to Vichy France by an organization called the Emergency Rescue Committee (it actually existed) to help rescue artists and writers. But Fry is faced with a choice: Does he help rescue the talented refugees he was tasked with saving or just “regular” refugees?

This moral ambiguity of Holocaust fiction is not new. As scholar Emily Millner Budnick argues in her 2015 work “The Subject of Holocaust Fiction,” “If the Holocaust narrative becomes simply about the Jewish (or gypsy, or homosexual, or handicapped) victim, who is good, and the German (or Nazi, Polish, or anti-Semitic) victimizer, who is bad, then the story of the Holocaust becomes simple and straightforward.”

Orringer echoed this idea — that stories of the Holocaust aren’t just straightforward, but contain nuance and depth — when we spoke.

“Despite the fact that there are certain elements of [Holocaust fiction] that have become familiar to us — descriptions of the camps, people being rounded up, being taken out of one’s home and sent into a kind of unimaginable existence — those larger tropes of Holocaust literature, they are composed of individual stories, and the number of individual stories is millions,” she said.

“Anytime a writer can explore a particular story and bring it alive with some poignancy, readers will just continue to be amazed by people’s fortitude, by what people are willing to do for others, or by the ways that that unimaginable adversity tests us and changes us. And I don’t think that can ever be exhausted.”

The successful works of Holocaust fiction I read for this piece make sure to note that they are “inspired by true events.” They remind you, the reader, that this really happened, even if it didn’t happen exactly as the writer is about to describe.

As scholar James E. Young argues in “Holocaust Documentary Fiction: Novelist as Eyewitness,” Holocaust fiction writers are “forcefully compelled” to remind readers that there is a factual basis underlying their stories. “By mixing actual events with completely fictional characters, a writer simultaneously relives himself of an obligation to historical accuracy (invoking poetic license), even as he imbues his fiction with the historical authority of real events,” he wrote.

Hunter believes that Holocaust fiction should always be rooted in true events and real people.

“There’s no more important time than now to be remembering these stories,” she said. ” And whether it’s based on the era, or based on a very specific person and what they experienced, it’s a chapter in our history that needs to be told and retold again and again in order for us to never forget what happened.”

When I asked Hunter why she decided to write her family’s story as historical fiction, not memoir, she explained that while the narrative is “absolutely based on truth,” what was missing was “the colorful human aspect,” aka what makes a book readable.

“What were my relatives thinking and feeling and saying and wearing? What was the weather?” she asked. “I wanted to honor the story truthfully and to honor the family’s experience of what they went through at the time, but I also wanted it to [be a book that] my kids could pick it up and almost feel as if they were there.”

By fictionalizing details (like Fry’s lover that Orringer invents in “The Flight Portfolio”), it allows the reader to be in the moment with the characters. It allows them to understand the Holocaust not as something that happened long ago, but as something that happened to real people.

And maybe these stories are staying popular because of what’s happening in the world today.

“The Holocaust also continues to compel readers and writers because it seems so unfathomable but, at the same time, is an embodiment of our fears,” Kantor of the Jewish Book Council said. (Just think back to summer 2018, when the separation of families at the U.S. border with Mexico were being compared to the early stages of the Holocaust.)

“Do you remember when you were a kid in Hebrew school?” Orringer asked. “You were told the horror, and that you should never forget. And it seemed kinda distant at the time. Under the current administration, that hasn’t been the case. What seemed like a pretty abstract principle is no longer an abstract principle.”

Orringer said she wanted to tell Fry’s story because “I want [readers] to know about how much difference a single person can make.

“I think that in the face of our country’s current official xenophobia, it’s easy for us to feel really disempowered,” she said. “And I think a story like Varian Fry’s reminds us that despite our limitations, we can make a difference individually, and the difference we make can change hundreds or thousands of other lives.”

Hunter echoed this sentiment — her book was released weeks after Trump’s inauguration, even though she had started it nearly a decade earlier. His election coincided with a rise of anti-Semitism on the right and the left in North America and Europe, and prompted accusations that he and his supporters either embraced white supremacism or did too little to condemn it.

“When I set off to write my book, I never thought it would feel so relevant and so timely. The themes of the Holocaust and anti-Semitism and survival against all odds and perseverance in the face of adversity …” she trails off.

“Look where we are today, it’s scary. We live in a world where the number of survivors is shrinking, and yet anti-Semitism seems to be on the rise in a lot of places. Maybe that’s part of what’s inspiring writers to write these stories down.”

And that’s possibly the most compelling reason for why we keep reading them.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.