This article originally appeared on Alma.

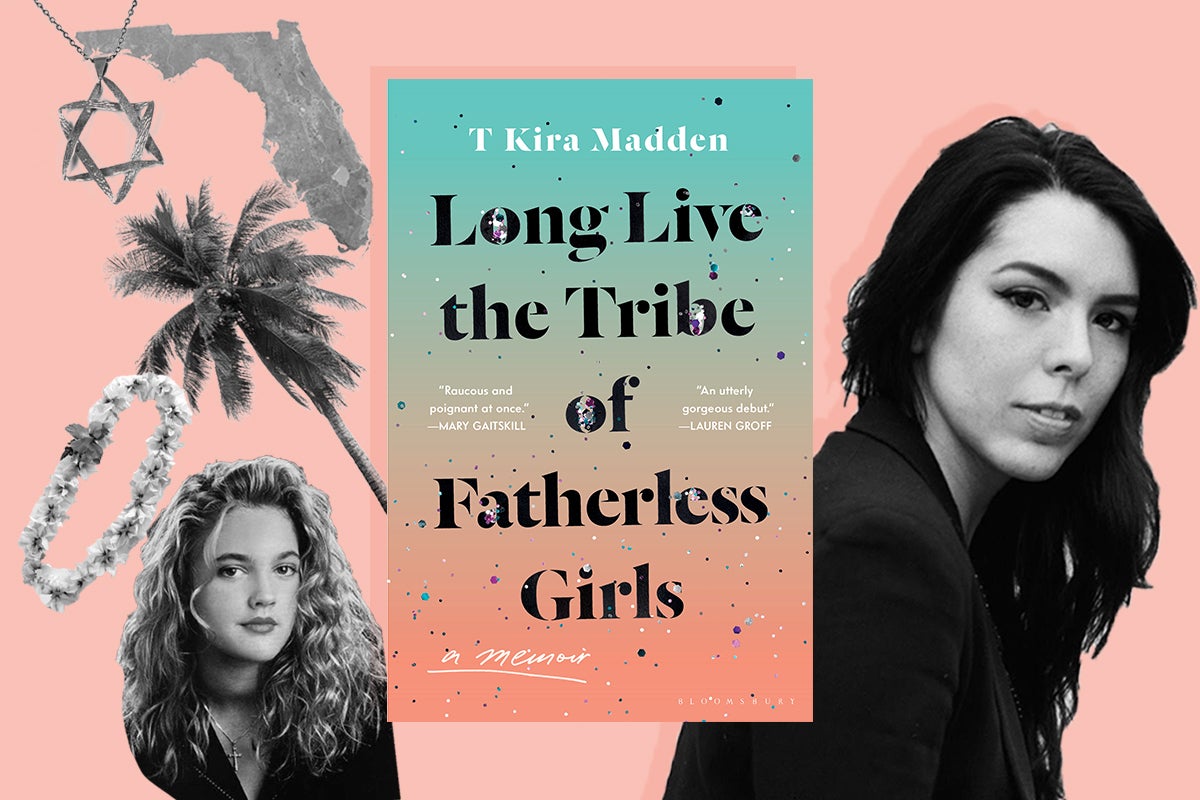

T Kira Madden’s gorgeous and remarkable debut memoir, “Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls,” chronicles her childhood in Boca Raton, Florida, as the daughter of parents who struggled with addictions.

“I wrote the book kind of accidentally,” Madden tells Alma. “But, I believed in the book, and went forward, because I found an agent who read it and said, ‘I think this could help kids like you. I think this could help other people going through the same.’”

Not only does the book dive into Madden’s childhood, but it weaves through her own path to figuring out her identity as a queer woman with a complex heritage — her father was Jewish; her mother is Chinese and Hawaiian. It’s a story of family, addiction, Florida, mannequins, fatherless girls, and yes, you must read it.

https://twitter.com/TKMadden/status/1098664391900303360

Here at Alma, we chatted with Madden about everything from growing up in a Jewish grandparent community to how Drew Barrymore — yes, that Drew Barrymore — saved her life.

Alma: Can you talk about the inspiration for the title of your memoir? What a grabbing title!

T Kira Madden: The title was not my idea, and I fought against it ’til the very end. My editor and agent and publishers always felt “Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls” felt the most true to the spirit of the book, and the most triumphant.

But I wanted the title [to be] a little darker, like ‘The Rat’s Mouth.”

“The Rat’s Mouth”?

“The Rat’s Mouth” was my title — the title of my heart. [It’s] the translation of Boca Raton, which I just thought was funny. My editor had a really great point that she felt “The Rat’s Mouth” was a punchline that closed, rather than an opening. So, I gave in and surrendered and we went with the long title that I was nervous no one would ever remember. And they were absolutely right. I’m so grateful that I lost because it does capture the spirit of the book, and people have really discovered it through that title — through feeling part of that community, or that tribe, or that energy. So I’m happy we did it.

Can you talk about what it was like growing up, navigating being Jewish, Chinese, and Hawaiian?

I didn’t understand what any of those components really meant, never mind as a kind of wild combination. I didn’t have any figures or role models or people in my life who had the same racial combination. But it’s something I’m so grateful for, that my parents always gave me a choice of how I wanted to identify.

My mother, as a Chinese Hawaiian woman, was raised in a Mormon household with Buddhist grandparents. And my father is of course Jewish from Long Island. They always let me learn about every different religion, every culture. I went to temple, I went to church, we did Chinese New Year’s — we did everything. They told me: Wherever you find your place, that’s your place. We’re not gonna tell you where you belong.

So that mix — which was confusing at the time — is something that was really part of my becoming [by] learning about all those different components of my identity.

Honestly, before your book, to me, Boca Raton is the place where Jewish grandparents go to retire. You’re obviously not a Jewish grandparent…

I did have Jewish grandparents in Boca Raton! Oh yeah. And I went to Jewish summer camp, in Roscoe, New York, and all [my camp friends were] from Long Island, but they all knew Boca and visited frequently because of their grandparents. So I never had to have the big goodbye at the end of the summer, cause I would see them through all of the winter.

But as a child, growing up in a retirement community — or maybe it’s not a retirement community, maybe my perception is off — what was that like?

Just really having to embrace being an outsider. There was no one like me in that community, at least in my school — I’m sure there were other people [like me] in Boca Raton. But at my school, one girl came out in middle and high school, one person total. And she was bullied so severely she had to switch schools. I didn’t know other Asian American girls, and certainly no Hawaiian people.

And I wasn’t bat mitzvahed the way everyone else was at my school, so that made me feel a little outside of something as well. But I created my own bat mitzvah at summer camp; I made bat mitzvah T-shirts at summer camp and they said, “I got lei’d at Kira’s bat mitzvah.” They were Hawaiian-themed, ’cause that’s what I would’ve wanted for my bat mitzvah, and I got to spend it at camp. But that’s how much I really wanted my bat mitzvah, and how much I really wanted to fit in with the kids at school, and with my community.

What was your mom’s reaction like to reading the book?

She’s been completely supportive. Every time I finished a section, I sent it to her. She’s my number one reader, she’s at all of my public readings. She’s my cheerleader.

https://twitter.com/TKMadden/status/1089906365668171777

We ultimately had a pretty happy ending, and I think she’s able to separate what our life looked like then — which she can admit was also really tough — [from now]. And the hope is in the idea that I could put a beating heart and a pulse behind the stigmatized idea of addicts, and what that looks like. That I could render real people and offer more humanity to that story.

You write briefly about how, at 22, you started teaching inmates in a county jail. What was that experience like? What advice do you give your students about writing their own stories?

I started teaching in jail when I was a student at Sarah Lawrence; it was part of their programming called “right to write,” a fantastic program. I worked for the MommyReads program and also [in] the women’s ward of the jail. We worked on literacy, helping women write children’s book themselves, and then we would record their voices reading the stories and send them to children in foster care, so they could learn to read and hear their mothers’ voices. Which was devastating and amazing. From there, I started working in a homeless center/rehabilitation center, which was men only.

They’re still the greatest students I’ve ever had — they have exceptional stories. They’ve been told for most of their lives that they don’t have a voice or anything to say, and as a result of that, they have everything to say that they’ve stored up. I don’t even consider myself a teacher as much as a facilitator who has helped them unlock the ways in which they can tell stories or create stories for consumption. It’s my favorite work to do: to tell them until they believe me that they have so much to say, and their voices are worth being heard and being shared. Helping them find their center of gravity and stand up inside of their own stories.

You write about deeply traumatic experiences you’ve been through — and I just kept thinking about how brave you are for sharing, for letting readers in like this. What did it feel like putting it down on paper? I talked to another memoirist a few weeks ago, and she’s like, I wish I had a therapist while I was writing my memoir.

Yeah, I’m grateful for my therapist, for sure. I think I had a bit of a different experience than many people when they’re writing their nonfiction work or memoir; many people find it’s excruciating to live in that space again. But I’m writing about things that happened 17, 25 years ago, sometimes more, and I couldn’t have written about it unless I was ready to write about it, unless I had that space. So, when I approached the work, of course I have to live inside of it, but I’ve spent so many years living inside of it, [it] feels more productive and positive to then craft that experience into something that I believe — and hope — is art.

The difficult part, for me, is the publication process, and opening up that dialogue with people. Some people I want to have a dialogue with, and other people don’t respect my story, or they’re strangers, and it feels invasive. That feels like a very different part of this business, and a different part of my brain, and it feels a little more vulnerable.

So as you start to do press for the book, have you had to deal with any invasive questions?

I’ve pretty lucky so far. I know they’re coming; of course, it’s about my life, and personal questions are completely warranted, but I also hope people can think about the craft of the book, and how much work was put into creating an object. Rather than, “What does your uncle think?” and “What does this person think?” and “Have you gotten in fights?” I hope it can stay about what the book is trying to say and how it was built.

My favorite part of books are the acknowledgements, and yours were so beautiful. I have two questions about them: First, in the second-to-last acknowledgement, you thank Drew Barrymore for saving your life with a book. Can you just expand on that a little?

When I reflect back [on my childhood], often people ask me, what literature did you have or wish you had? I only had one book, and that was Drew Barrymore’s campy memoir “Little Girl Lost”, which was ghostwritten but … At that point in my life, I didn’t have the vocabulary or context to understand what addiction was. All I had was this book of someone describing the same things that were happening in my household. I felt like Drew Barrymore and I were the only two kids on earth who shared this secret, and this story. It was like my Bible. I took it with me everywhere; I kept it under my pillow.

When my parents were using at their worst, I would just read her story and understand, oh yeah, that’s why Drew Barrymore’s dad is drinking boat fuel and my dad is trying to drink extract and fuel. She was really my lifeline, and the only person I thought would understand what I was going through. I didn’t understand yet that people all over the world deal with addictions in their household. So she did, in a way, save my life. That book saved my life.

Wow. OK, my other question about the acknowledgements is at the end, you drop that you’re engaged to Hannah, who appears in the book, which, mazel tov! That’s so exciting.

Thank you!

What has the support of your partner been like throughout this process? Are you planning a wedding as you’re releasing a book?!

We are planning a wedding, which I thought would be terrible timing, but it’s actually fantastic because I have distractions from the book and reviews. I can think, here’s what really matters to me: marrying this woman. She’s amazing. I wouldn’t have a book without her. She’s my secret weapon. She reads everything, she edits everything, and she’s a brilliant writer. She’s a poet. And she’s been completely supportive.

We lived in Massachusetts for a year, while she was there for a fellowship, so I couldn’t see my therapist all the time as I was working through some of the more difficult parts of the book. But, because I had her, I felt like I had grounding and support. In her own work, she works with autobiography, so she understands the compromises and the difficulties of conversations you have to have with someone, and maintaining your moral compass when you write about real people and real events. So, those are conversations we have all the time.

What has the reaction to the memoir been like for you?

It’s still not out yet, so it’s still surprising when I hear about people reading it. So far, mostly supportive — and so far, none of the negative reviews have hurt my feelings, because none of them have been cruel so far. They’ve just been kind of… [laughs].

“The Greeter” piece was published with The Sun last weekend, and the one negative thing someone said was, “There are too many drugs in this piece.” So, that’s something I can laugh at, you know?

Someone else said it was “overly precious and overwritten.” And that’s something I feel OK about! I approach language, I hope, with a scientific precision. I think about every syllable and I read every sentence aloud, so if someone feels like it’s overwritten, it is! I think about it a lot.

What’s the one thing you hope people take away from your story?

I hope people feel the power of being an outsider. I hope people can recognize some version of themselves, or some element of themselves, in the book. It’s likely no one will be just like me — but they might feel that sense of being an outsider, being a former loser, having family secrets and trying to reckon with those, or having experienced assault or addiction in the household. There are so many elements of identity and pain and love in the book, and I hope people can meet me there. Not necessarily take away a moral of the story, but to know that somebody else is there. And is meeting them. And they’re not alone in that experience.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.