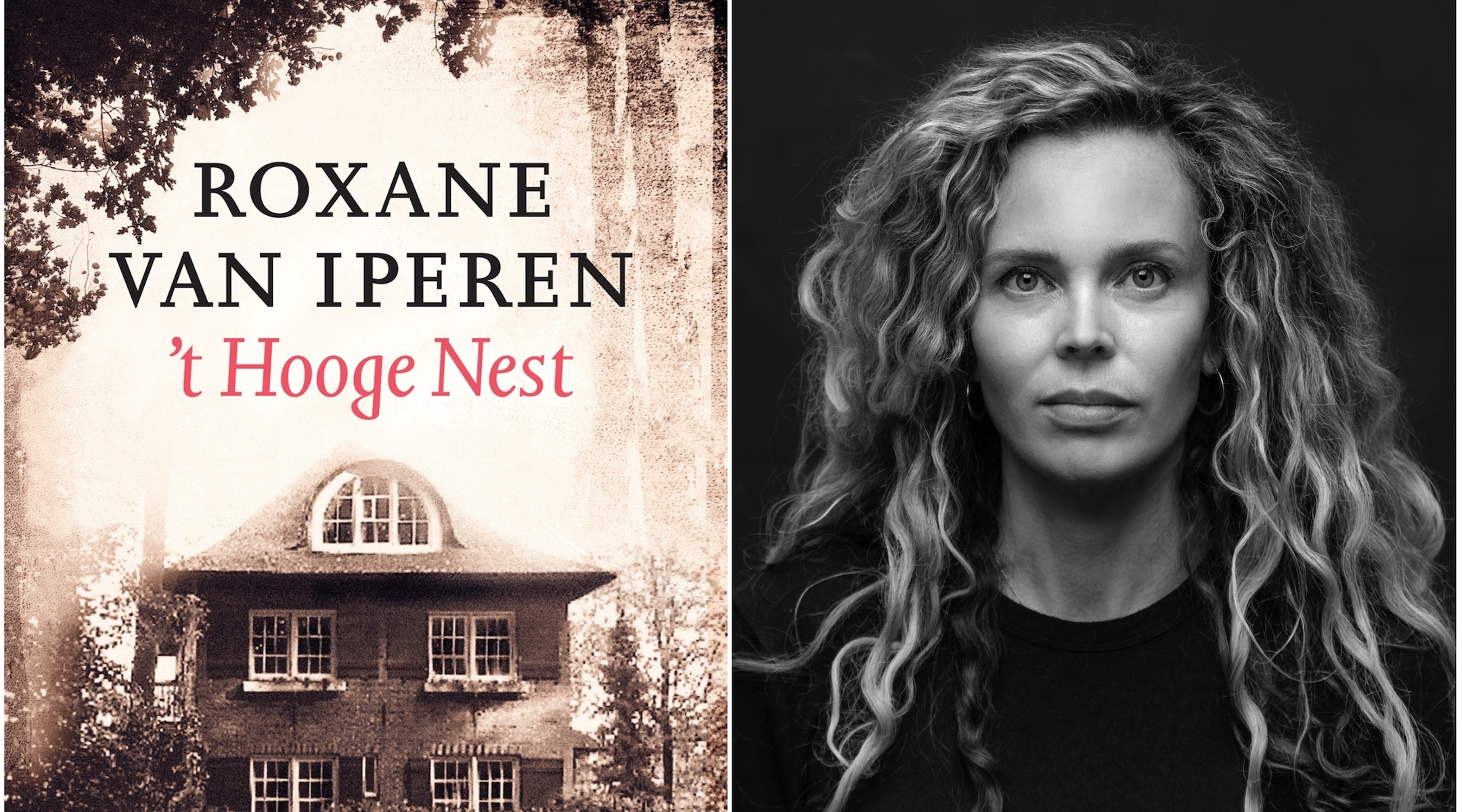

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — Despite its rustic charms, the dream home that Roxane van Iperen and her partner bought nearly ruined their marriage.

Van Iperen, a 42-year-old novelist, underestimated the amount of renovating needed on the countryside estate east of Amsterdam. She bought the place in 2012 with Joris Lenglet as a home for the couple and their three children.

“We almost separated by the time it was done,” she recalled in a November interview on the NPO1 television channel.

But amid “the arguing, misery and work,” as she described it, the couple made discoveries whose significance they realized only months later: During the Holocaust, their new home had been the center for one of Holland’s most daring rescue operations conducted by Jews for Jews.

Recounted in a best-selling book that van Iperen published last year, the story generated strong media interest amid a wave of introspection about the Dutch society’s checkered Holocaust-era record. In bookstores, “The High Nest” stayed for weeks on the top 10 list of locally produced nonfiction.

“Many Jews resisted, but of most of them we know very little,” said the Jewish filmmaker Willy Lindwer, who has produced several documentaries on the Holocaust in his native Netherlands. He said the “High Nest” story “shows not all Dutch Jews went like lambs to the slaughter, and that’s very important.”

But to general readers, part of the book’s appeal lies in the strong characters of the people who did the rescuing at van Iperen’s home: sisters Janny and Lien Brilleslijper and their families.

Daring anti-fascist activists — Janny fought as a volunteer combatant in the Spanish Civil War — they used connections to hide from the Germans in the house in Naarden, situated 10 miles east of Amsterdam. But at great personal risk, they then opened their safe house to Jews and others in need.

Van Iperen found evidence of the sisters’ ingenuity as soon as the renovations began, discovering double walls, secret doors and walled-off annexes that had been concealed so well that they were left undetected for decades. In one secret space, van Iperen even found wartime resistance newspapers.

Dozens of Jews passed through the safe house, which is “perfectly located near Amsterdam but in the middle of nowhere,” van Iperen said. The nine-room estate is mostly hidden from view by large trees that afforded privacy to the tenants.

The operation’s secrecy kept it out of the history books even though it was a rare case in which Dutch Jews not only escaped the genocide but helped others avoid capture.

Even as they were making these discoveries, van Iperen and her partner did not register their significance — at first.

“The discovery story sounds romantic but the truth is, we just weren’t aware of the findings,” she said in the interview. “It was an old house — that’s also what drew us to it — and so you naturally discover things. We talked about it. But then we just closed the hidden space and installed a new floor on it.”

The renovations coincided with major developments in attitudes to the Holocaust in the Netherlands, which received its first national Holocaust museum only in 2016.

In 2012, the Netherlands saw the creation of a grassroots network of homeowners whose properties once belonged to Holocaust victims. They now open dozens of houses in some 20 municipalities for visits by the public each year on the Dutch memorial day.

Amsterdam, meanwhile, is preparing a huge Holocaust monument at its center.

This year, the city and The Hague paid millions of dollars in restitution to victims from whom it had unjustly collected taxes.

Lien Brilleslijper with her daughter Jalda in Berlin in the 1970s. (Courtesy of the Brilleslijper family)

In November, the national railway company announced it would look into compensating victims that its workers helped transport. That triggered similar action last month by Amsterdam’s GVB transportation company.

Amid these developments, which were accompanied by a steady stream of news reports and books on the Holocaust, the secrets of van Iperen’s house kept beckoning. They eventually put her on a six-year journey of discovery through interviews, studying archive material and cross-referencing information with survivors’ testimonies.

The sisters, intellectuals from a Liberal Jewish family, arrived at the estate near Naarden in 1943, amid deportations to death camps and growing awareness of the annihilation of Europe’s Jews by Hitler.

By that time the Nazis had killed 75 percent of the Netherlands’ prewar Jewish population of about 140,000 — the highest death rate in Nazi-occupied Western Europe.

“Everyone who could was in a panic to find a hiding place,” van Iperen said.

And yet at the Brilleslijpers’ house, “there was actually a lot of music and lust for life during that time, which makes it different to the typical survival-in-hiding story we know in this country,” van Iperen said.

She found sheet music that the sisters — Lien was a well-known singer — and their guests composed and performed on musical evenings. There were worldly debates and garden dinners — several of the people in hiding were artists — amid the laughter of children.

One of the rug rats was Robert Brandes, the 5-year-old son of Janny and her husband, Bob Brandes. Robert Brandes, now 79 and an artist, gave van Iperen, who tracked him down, a yellowing photograph taken at her home in 1943. He is seen splashing in a metal tub on a sunny day in the backyard flanked by his cousin, Kathinka Rebling, Lien’s daughter, and another child.

Around the corner from the Jews in hiding lived the lover of Anton Mussert, the head of the pro-Nazi NSB party and the top collaborator with the Nazis. He would often stay over, van Iperen also discovered.

But in June 1944, Eddy Musbergen, one of the hundreds of Dutch gentiles who betrayed or hunted Jews in hiding, reported his suspicions about the estate to the authorities.

It was an eventuality for which the sisters had planned, according to Rebling, Lien’s daughter. During the Gestapo raid, her mother removed a vase from a window sill overlooking the access path — a secret sign for other tenants that the house had been compromised.

The raid occurred when Janny and her son were out. Janny saw the vase as they returned and attempted to catch up to Robert, who was skipping along ahead of her. But the Germans saw them and they were arrested.

The sisters and their families were sent to the Westerbork concentration camp, Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen.

At Bergen-Belsen, Janny met the family of Anne Frank.

“She was concealed in a blanket,” Janny, who died in 2003, recalled in a 1988 documentary by Lindwer. “She had no more tears to cry. They had run out a long time before.”

Janny went to check on Anne a few days later and saw Anne’s sister, Margot, lying dead on the floor. Anne died shortly thereafter, Janny said.

Both Brilleslijper sisters survived the Holocaust — partly because they were persons of interest to the Nazis due to their anti-fascist credentials, van Iperen discovered. This prevented them from being sent directly to the gas chambers at Auschwitz, allowing them to survive.

Robert Brandes was spared deportation because after his detention, he was deemed by the Nazis to be only half Jewish. Rebling, who was 3 and whose parents were both Jewish, was spirited away from a detention facility by a resistance fighter and survived the war in hiding.

“That we are still alive,” Rebling said during the November interview with NPO1, “can only be explained by an unbroken chain of miracles.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.