In 2013, Nashville puppeteer Brian Hull was browsing through the stacks at the Nashville Public Library when he came across an obscure Polish children’s book with a wizard on the cover.

“When I saw the book, I thought, what is this, some Harry Potter ripoff?” said Hull, who runs the library’s resident puppet troupe and produces independent puppet shows through his company, BriAnimations Living Entertainment. “Then I saw it was copyrighted 1933.”

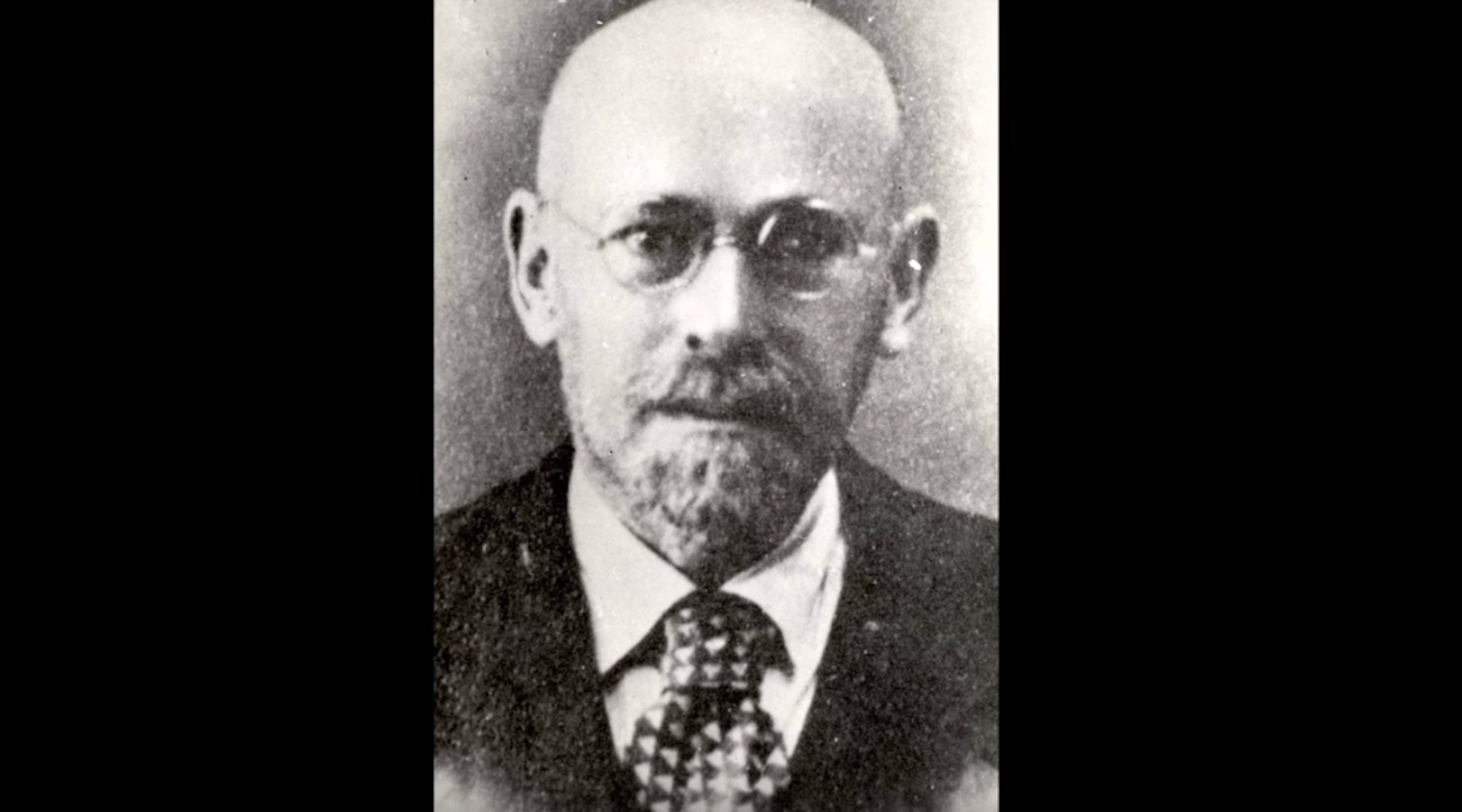

“Kaytek the Wizard” is the work of Janusz Korczak, a Polish Jewish pediatrician and author best known for refusing to abandon the children of his Warsaw orphanage when they were deported to Treblinka, despite offers of refuge that might have saved his life. The book became available in English only in 2012.

“I started reading it and I just became obsessed with it,” Hull said. “I just thought: What is this man doing? This is like no other children’s book I’ve ever read.”

Hull went to work in his basement adapting the novel as a puppet show, complete with original music and drawn animations. The show premiered to a sold-out audience at the 2016 Nashville International Puppet Festival. Hull has scarcely stopped performing it ever since, staging it at theaters, festivals and schools across the country.

“As I learned more about Janusz Korczak,” Hull wrote in an educational pamphlet distributed by the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, “I couldn’t believe I had never heard of him.”

Killed by the Nazis in 1942, Korczak left behind a small but formidable body of novels, poems and pedagogical insights that continue to inspire readers, educators and activists more than seven decades after his death. His ideas live on not just in educational circles, but in international law.

Korczak was among the earliest supporters of the notion that children have rights, an idea he promoted on a radio program he hosted before the war and as a signatory to the 1924 Declaration of the Rights of the Child.

Born Henryk Goldszmit in Warsaw in the late 1870s (the exact year isn’t known), Korczak was raised in an affluent Jewish family whose fortunes faded after his father took ill and died. Korczak studied medicine at the University of Warsaw and became a pediatrician. But in his 30s he abandoned the practice of medicine to become the head of a Jewish orphanage, where he began to put his ideas about children’s education into practice.

Nashville Puppeteer Brian Hull’s adaptation of Janusz Korsczak’s children’s book “Kaytek the Wizard” has played across the country. (BriAnimations Living Entertainment)

A firm believer in children’s rights, Korczak instituted democratic governance in the orphanage, including establishing a parliament where the children set their own rules and administered their own affairs. If a rule was broken, the offender could be brought before a children’s court overseen by a rotating group of judges. Korczak also founded the first national children’s newspaper and wrote more than two dozen books.

“Many of his actions with the children I would say are now considered social and emotional learning, which is now the in-word in education,” said Sara Efrat Efron, an education professor at National Louis University in Chicago. “There is a lot of effort now to find ways of focusing on emotional and social growth, and the methods that are recommended are things that Korczak did day in and day out. So he was really ahead of his time, and maybe ahead of our time.”

Today, societies dedicated to Korczak’s legacy are active in more than a dozen countries, including in the United States. Schools inspired by his pedagogical ideas exist in Germany, Holland, Poland and Russia. His teachings are the basis of a summer camp in Poland, and his life is the inspiration for the song “The Little Review,” by the Canadian folk singer Awna Teixeira. In 2012, a bronze relief of Korczak was unveiled at the University of British Columbia. Translations of Korczak’s writings continue to be published, including a 2013 Chinese edition of his children’s book “King Matt the First.”

Korczak’s efforts on behalf of children were all the more remarkable, Efron says, because they were undertaken amidst the most trying of conditions.

With the Nazi occupation of Poland, Korczak was forced to relocate his orphanage to the Warsaw Ghetto. As the moral condition of the surrounding culture deteriorated, Korczak declined to delude the youngsters in his care about the realities of the world, yet neither would he succumb to despair, continuing to believe that children were the best hope for humanity.

That conviction was severely tested in August 1942, when the Nazis came to collect the 190 children in the orphanage. In what would come to be the story by which he is best remembered, Korczak, by then a prominent figure in Poland, declined offers that might have enabled his escape. Instead, he dressed his charges in their finest clothes and led them through the streets to the deportation point, where they were placed on trains to Treblinka.

“Korczak’s clinging to hope did not stem from naivety or blindness,” Efron wrote in a 2016 article, “but from a calculated choice, an existential understanding that despair means giving up on change, thus conceding the future.”

Decades after his death, Korczak’s ideas would be promoted by Poland’s postwar government.

The U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the General Assembly in 1989, was first proposed by Poland in 1978. The Order of the Smile, an international award given by children to adults distinguished in promoting their interests, was started in Poland in 1968 and recognized by the U.N. secretary-general in 1979.

This year, the award went to Marta Santo Pais, the U.N. special representative on violence against children, who delivered the keynote address at a November conference on Korczak’s legacy, pedagogy and advocacy for children’s rights held at Columbia University. The conference was sponsored by the Polish Cultural Institute New York, among others.

“Korczak’s main idea is that a child is a human, only a small human, and therefore his or her rights cannot be treated differently from adult rights. That was revolutionary for his time,” said Anna Domanska, acting director of the institute. “So was his innovative way of running a center for orphaned children. Korczak’s activity was also made possible by the general social climate of interwar Poland, where citizens, enjoying their freedom after 123 years of foreign domination, wanted to express that freedom as fully as possible.”

In 2012, the lower house of Poland’s parliament, the Sejm, declared the Year of Janusz Korczak, marking 70 years since his death and 100 since he founded his orphans’ home.

“This allowed us to commemorate the old doctor and fix his memory not only in Polish reality, but the world’s,” said Marek Michalak, Poland’s Children’s Rights Ombudsman from 2008 to 2018, chancellor of the International Chapter of the Order of the Smile, and president of the International Janusz Korczak Association. “Korczak was not just as a victim of the Holocaust, but also as the first spokesman for children’s rights, an outstanding pedagogue and author.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Polish Cultural Institute New York, a diplomatic mission of Poland’s Foreign Affairs Ministry that promotes comprehensive knowledge of Poland, Polish history and national heritage. This story was produced by JTA’s native content team.

More from Polish Cultural Institute New York