JERUSALEM (JTA) — A couple of months ago I was waiting to use an ATM near my house, flicking through Twitter as the line inched its way forward. Finally, after about 10 minutes and several tweets, I reached the machine and was getting ready to insert my card when an Israeli man ran over from the corner, some 15 yards away, and tried to cut in front of me.

“What are you doing?” I demanded.

“It’s my turn,” he replied in a tone that seemed to be both condescending and shocked by my apparent impertinence.

When I pointed out that he had not been on line, but had been hanging out and chatting with his friends, he grew heated, insisting that he had stopped by before I arrived and told the person in front of me that he was claiming a spot.

At no point had he actually bothered to stand in the line himself. That is, if you could call it a line. It was more of a clot, actually. Those present mostly gathered higgledy-piggledy, repeatedly asking each other who was ahead of whom. In Israel, the concept of an orderly queue, so unremarkable to immigrants from Europe and North America, can still seem to be an entirely foreign idea.

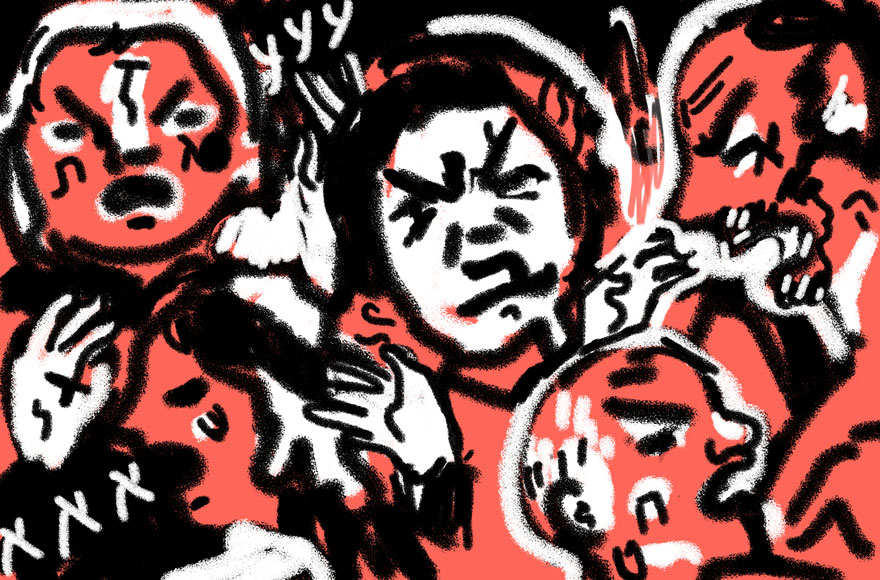

This tendency to engage in behavior that would be considered rude elsewhere extends to other aspects of Israeli life. It is not unheard of to be boarding a bus and watch ticketed passengers duck under the arms of a rider who had the temerity to slow them down by paying the driver in cash. Or to be approached by random strangers who begin asking why you immigrated, how many children you have and how much you earn.

On Israeli roads, a turn signal is not a sign of intent but of weakness.

The Israelis’ reputation as a rude, abrasive or merely boundary-less people has made its way around the world — surviving even its new incarnation as “start-up nation.” Famously, in 2015, the tech firm Intel presented its employees with a guide to working with Israelis that warned them to “expect to be cut off regularly” and that “visitors are often taken back by the tone or loudness of the discussion.”

Many English-speaking immigrants to Israel — or Anglos, as they are known locally — have long complained about the stark differences in cultural norms and expectations that complicate relations between the two groups.

“Israelis are notoriously late; super casual in dress code and speaking,” said Daniel Rosenthal, an immigrant from Tampa, Florida. “They tend to be too personal in their opening remarks, sharing things like how many kids they have.”

Dave Levy, another immigrant, said that “arguments can easily get loud and verbally violent, yet never physically violent. There is very much a culture of arguing.”

There is no personal space, complains Melissa Amar, originally from Schwenksville, Pennsylvania.

“In America, when having a conversation you’re not right on top of the other person,” she said. “Here I find myself stepping back when talking to people.”

Others, however, said this directness and sense of familiarity also has its upsides.

Ilana Gamliel, originally from Long Island, said that here, “people are much more helpful and strangers will happily hold my baby.” Leah Rachelle Berman notices “how easy it is to strike up a conversation with a native Israeli.”

“I like that they are direct, not hesitating or beating around the bush — no false airs,” she said.

What Israelis call directness and many outsiders consider rude is likely caused by a variety of factors, including the country’s small size, a socialist past that emphasized a radical egalitarianism, a sense of kinship (or perhaps entitlement) among Jews arriving from all over the world and the hard-charging ethos inculcated by Israel’s military culture in the wake of decades of war. (In the army, it is common to call officers by their first names once basic training is over.)

Israelis often do not even realize they are perceived as rude by foreigners, said Reuven Ben-Shalom, a former Israeli Air Force officer who runs Cross-Cultural Strategies Ltd., a consulting firm that teaches foreigners how to deal with the culture here.

“Most times Americans see Israelis as prying” in a way that in the U.S. “can destroy relationships. But it’s just Israelis being their typical selves,” he told JTA. “It’s just classic cultural differences — different countries develop different cultures.

“Israel is like an island in the Middle East. We can feel very Americanized, but we have developed here a unique culture of our own. Once a culture takes off after several decades, you find that there are behaviors that would seem completely strange” to outsiders.

Shalom’s company website warns that Israelis are “straightforward and blunt, tend to talk instead of listen, teach instead of learn, and preach instead of recommend and contribute.”

“We are all in this aggressive attack mode,” he said. “People say things and we go on the defense. There is a theory that because of life in the Middle East, our very nature is always fighting for existence and holding a sword in one hand, and that finds its way into all avenues of our lives.”

Part of the issue may be that Israel is a hastily mixed polyglot culture with Jewish immigrants from Europe, the Americas, North Africa, Arab lands, Ethiopia, India and the former Soviet Union. Each group holds to its own expectations and standards, said Tami Lancut Leibovitz, a local etiquette instructor.

“People here are under stress 24 hours a day — this is the first thing. The feeling is that Israelis are rude not because they are bad or want to do it on purpose, but we in Israel we don’t know what manners and etiquette are,” she told JTA, adding that there is a definite lack of education in this field in the school system. Training, she says, starts early and there is not enough of it.

Contrary to popular belief, Leibovitz said, the way that Israelis behave actually bothers many of them.

“No one can feel good when someone comes into his private space,” she said. “We are human beings. We can’t stand it, but many don’t know how to put a finger [on the problem] and say what it is.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.