RIO DE JANEIRO (JTA) – Freddy was 5 years old when he saw a paving stone shatter his dad’s storefront in Berlin. Later, while his family watched, Nazis beat up his father. In 1933, Adolf Hitler had already made life unbearable for the Glatts, forcing them to scramble to Belgium.

“I was too young to remember with details, but I do remember my dad said ‘Rush inside!’ and so we ran. I felt terrified,” he said of the attack on the store.

Eighty-five years later, Freddy Siegfried Glatt now serves as president of the Brazilian Association of Holocaust Survivors in Rio de Janeiro. His life story has just become a song that was composed and sung by the Brazilian-born grandson of his late first cousin Max, who at the age of 71 immigrated from Rio to Israel.

“Telling family stories about Nazism is extremely important to secure that the Holocaust never repeats again, with anyone,” said Lazar Wall, the Yiddish pseudonym of Luis Waldmann, who decided to put Glatt’s life story to music on the day in April when his elderly cousin published his memoirs, “They Stole My Childhood.”

Wall, a 39-year-old musician who records as One Man Mambo, spent most Jewish holidays and family get-togethers with Glatt, whom he calls “uncle.” He titled the song “101 Jerusalem” after the Brussels street address of one of the Glatts’ last hiding places.

“This is my first Jewish-themed song, which I showed to Glatt when it was ready as a surprise,” Wall told JTA. “To me, it represents the resistance and unity of the Jewish people, despite the anti-Semitism that persists to this day.”

With the move to Belgium, Glatt was enrolled in a public school and joined the Zionist youth movement Maccabi Hatzair. The German-speaking boy learned Flemish, Hebrew, Yiddish and French. Anti-Semitism existed there, too, and the kids were often sworn at, spat on and beaten.

When the first air raid struck Antwerp in 1940, Belgium no longer felt protected from the war. The advance of Nazi Germany called for a new getaway and his “opa” – grandpa in German – Salomon booked four spots in the back of a dump truck heading to the French border. Glatt’s two teenage brothers, Bubbi and Heinz, were to travel by bicycle and meet them.

“The thousands of refugees along the way looked like the Hebrews fleeing Egypt,” Glatt recalled.

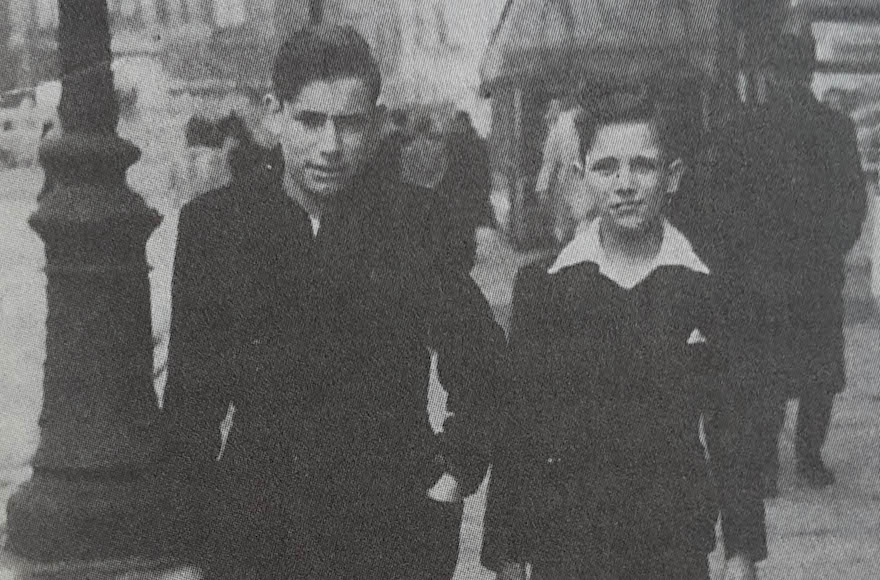

Freddy Glatt, right, with his brother Heinz in Brussels in 1941. (Courtesy of Freddy Glatt)

Shortly after crossing into France, the family boarded a train that was later targeted by two German Stuka fighter planes. Shrapnel struck Glatt’s leg, which took months to heal. The family settled near Toulouse in Vichy France, but the two brothers never showed up. By that time, his parents had divorced over his father’s gambling habit, and his father had moved to Brazil.

“They told me there were snakes walking in the street in Brazil,” Glatt said with a loud laugh.

Incoming refugees and a newly arrived acquaintance shared reports that his brothers had driven an abandoned car back to Belgium, moved back to their family’s home and reopened their grandfather’s store. Ecstatic at the news, Salomon longed to depart. The plan was to retrieve his life savings still hidden in Antwerp and whisk the family out of Nazi Europe.

They traversed Nazi-occupied France initially in a Belgian-built Minerva limousine with the help of a people smuggler, then on foot and by train. The family reunited in Antwerp. Salomon, whose savings were intact, started running his business again. But soon they’d be made to wear the yellow Star of David on their clothing.

A year later the Jews of Antwerp were ordered to move to Heusden, a village near the border with Germany and Holland. Their deportation to the extermination camps was held up, though, as Germany was too busy transporting millions of Jews from Eastern Europe to their deaths.

At 13, Glatt couldn’t have his bar mitzvah.

“There was no rabbi, no tallit, no tefillin or Torah in Heusden,” Wall said. “He had his bar mitzvah at the age of 85 in the Copacabana synagogue here in Rio.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LyHPBeQ5U9I

The Glatts were allowed back to Antwerp, except for the older boys: Bubbi and Heinz were sent to work in a coal mine. In 1942, both were summoned to work on the Atlantic Wall, a fortification meant to contain an expected Allied advance. Once on the train, they instead were taken to Auschwitz.

Meanwhile, the Gestapo, helped by local spies such as the Flemish Hitler Youth, actively hunted the Jews who remained in Belgium. Glatt’s grandparents Salomon and Chawa were found and deported to Auschwitz. Decades later Glatt learned that Salomon, Chawa, Bubbi and Heinz were murdered in Auschwitz in 1942.

“In a new effort to hide from the Nazis, Freddy and his mom moved again, now to a small apartment at 101 Jerusalem St. in Brussels’ Schaerbeek district,” Wall said. “The bathroom was tiny, meaning Freddy had to use a public shower, carefully hiding his circumcision.”

At the age of 14, Glatt started working as an assistant to a newsstand owner. At night he worked in a clandestine battery factory, and between shifts would draw Mickey Mouse-themed cards for sale at a stationery store. He would also steal train tracks and sell them as scrap.

The money afforded him and his mom rare visits to the movie theater. The films were preceded by newsreels depicting Luftwaffe bombs raining down on London and Operation Barbarossa crushing the Soviet Union. Glatt often snuck into the Palais des Sports arena to watch wrestling, boxing and other sporting events.

As the war went on, persecution and scarcity worsened, and Glatt’s mom, Rozalia, asked the chief rabbi of Belgium to find her son a safe place. With support from the Belgian and Jewish resistance, and from Elisabeth, the Queen Mother of Bavaria — whose efforts on behalf of hundreds of Jewish children earned her a designation as Righteous Among the Nations — Glatt set out for a school for Catholic boys.

From the playground there he could see hundreds of American B-17 bombers headed for Germany. The sight of maimed Nazis, repelled by American and British soldiers just in from Normandy, was another good omen.

When the Allies finally liberated Belgium in September 1944, Glatt reunited with his mom and both started frantically to look for the missing relatives, still unaware of their fate. In 1947, mother and son moved to Brazil. Glatt’s dad was no longer addicted to card games, and the couple remarried in Rio de Janeiro.

Glatt has lived in Rio ever since. He married his wife, Betty, in 1954, and they have three children, six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Wall’s song, sung in English, tells the story in telegraphic images over an insistent, mournful beat, ending with both a taste of Glatt’s freedom and a reminder of his brothers’ grim fate.

Freddy Glatt, shown in April 2018, has lived in Rio de Janeiro since the end of World War II. (Courtesy of Glatt)

“Wall’s song about Glatt translates the importance of this type of art as vehicle to transmit authoritarian historical periods and mainly show what intolerance, racism and prejudice are capable of generating,” historian Silvia Rosa Nossek Lerner told JTA.

Born in Rio to Holocaust survivors who fled Germany in the late 1930s, Lerner is the author of a book in Portuguese titled “Music as a Memory of a Drama: The Holocaust,” for which she translated Yiddish songs composed and sung in the ghettos and concentration camps. She said Wall’s song is in the tradition of such songs.

“They composed to occupy their time to sublimate feelings, which they could not understand and could not even answer,” Lerner said. “These songs help us to understand a little of the suffering that the Jews spent in these years of German domination, showing hunger, longing, hope for better days, concern for the future of their children and proves that even in difficult times, one can produce art.

“Music has the power to unite feelings, review emotions, remember stories, coexistence, memories and losses, and translate expectations and hopes.”

Wall hopes his song lives up to her praise.

“If youths come to understand what the Holocaust was through this song, our goal will have been achieved,” he said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.