RIO DE JANEIRO (JTA) – Gabriela Pszczol Krebs is not alone in her mixed feelings about Brazil’s presidential election runoff, pitting the far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro against the leftist Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad.

“Both of them have ideas that I abominate and feel revulsion for,” Krebs, 44, a psychoanalyst from Rio, told JTA. She has decided to cast a “none of the above” option. “One will win, but not with my help. It’s my form of protest.”

Unlike Krebs, most Brazilian Jews have apparently chosen to take a more active role in what seems the most polarized election ever in the world’s fourth-largest democracy. Brazil is still struggling to leave behind its worst-ever recession and shake off the vestiges of an epic corruption scandal that hit the highest levels of government and business.

The Conservative lawmaker Bolsonaro – his middle name, Messias, literally means “messiah” – has been soaring in polls, holding about a 20 percent lead over his far-left rival Haddad.

Like evangelical and deeply conservative politicians in the United States, Bolsonaro is highly divisive among Jewish voters: He is ardently pro-Israel, but has also run a campaign pledging to restore law and order and fight corruption with language some have called “fascist” and worse. He waxes nostalgic about Brazil’s 1964-1985 military regime, and derided gays, women and minorities in the name of “making Brazil great.”

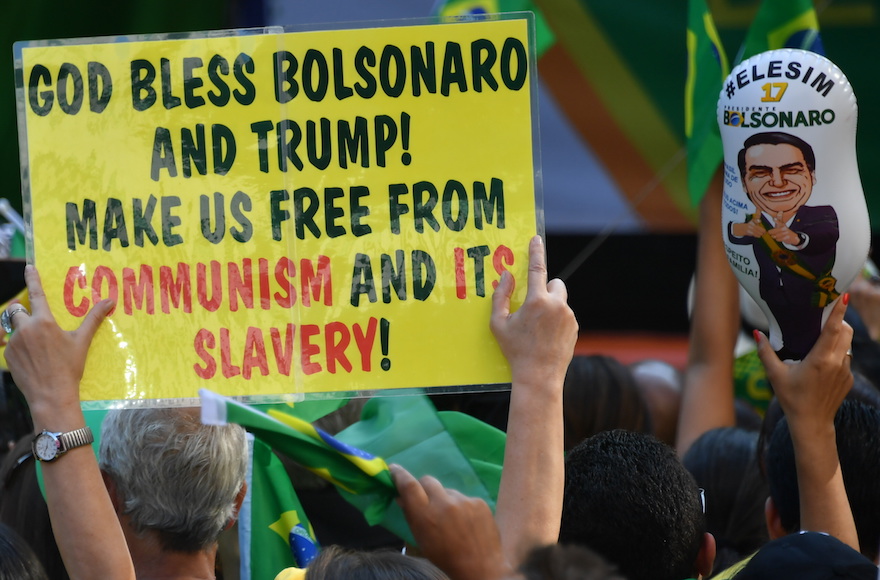

His rise is said to parallel that of other populist and nationalist politicians worldwide who often employ similar rhetoric, including President Donald Trump.

As Sunday’s election approaches, the seven-term congressman is the focus of fierce debate in Brazil and beyond over how to describe a candidate whose eclectic mix of policies and harsh language thrills supporters and terrifies detractors.

Fernando Lottenberg, president of the Brazilian Israelite Confederation, measured his words as head of the country’s umbrella Jewish organization to comment about the dispute.

“The Jewish community is quite diverse and we will work so that political differences do not affect our unity,” he told JTA.

Krebs said the polarization in the Jewish community is a reflection of the country.

“We are in a big darkness, a huge economic crisis, urban violence, unemployment and more,” Krebs said. “The feeling of helplessness is gigantic and people are willing to grab any trace of hope.”

The 63-year-old Bolsanaro is polling at about 60 percent of the vote in the one-on-one match against Haddad, a former mayor of Sao Paulo. In the first round of balloting on Oct. 7, Bolsanaro won over 49 million votes — close to the majority needed to avoid a runoff. The Jewish vote is seen as mostly matching that of the upper middle class and the overall totals.

Haddad, 55, is backed heavily by ex-president Luis Inacio Lula da Silva, who is serving a 12-year prison sentence for corruption and money laundering after once being dubbed the world’s most popular politician by former President Barack Obama.

Following nearly 15 years under da Silva and his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, Latin America’s economic locomotive began to derail. What was called the world’s largest corruption probe, Operation Car Wash, exposed billions of dollars in graft, igniting public anger. The effects of that corruption, combined with the recession, were enough to sweep Rousseff to impeachment in 2016 on the suspicion that she was complicit. In April, Lula was jailed.

Critics say Haddad has inherited their baggage.

He frequently says Bolsonaro is “extreme” and represents “a risk” to democracy. His Workers’ Party has gone so far as to liken his opponent to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in campaign videos.

Bolsonaro, who brags that he has never been accused of corruption during his nearly 30-year political career, has pledged to aggressively strengthen law and order after nearly 64,000 murders last year, a rate some six times higher than in the United States. The retired army captain, who represents the Rio de Janeiro state in the National Chamber, also espouses a return to traditional family values and a free economy.

Although most Brazilian Jews belong to the upper middle class, the longtime economic crisis has squeezed family budgets. For instance, requests for scholarships to Jewish day schools have skyrocketed. Two Jewish day schools in Rio raised some $2 million in scholarship donations in separate campaign blitzes. Last year, all 15 Jewish schools in Sao Paulo gathered $3.6 million in two days with the same goal. Some 700 Brazilian Jews immigrated to Israel last year, the highest rate since 1948.

For many Jewish voters, Bolsanaro’s pledges to fight corruption, stem urban violence and fix a fragmented economy make him a dream candidate.

So, too, does his stance on Israel. Bolsonaro has declared he will move the Brazilian embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. His first international trip as president, he said, will be to Israel, with which he will seek to broaden the dialogue. And he promised to close the Palestinian embassy in Brasilia.

“Is Palestine a country? Palestine is not a country, so there should be no embassy here,” Bolsonaro said weeks ago. “You do not negotiate with terrorists.”

For these Jewish voters, Haddad means the continuity of the longtime anti-Israel sentiment of da Silva and Rouseff. During his campaign, Haddad paid frequent visits to Lula in jail seeking political advice. One low point in Brazil-Israel relations came in 2014, when the Brazilian government recalled its ambassador to Israel for consultations during that summer’s war in Gaza, and a former special adviser to Rouseff described Israeli military actions there as a “massacre.”

Bolsonaro supporters take part in a rally along Paulista Avenue in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Oct. 21, 2018. (Nelson Almeida/AFP/Getty Images)

Jewish supporters of Bolsonaro also remember da Silva’s recognition of Palestine as an independent state in 2010, seen as part of his alignment with extremist governments such as Iran and Libya. At that time, Brazil donated $10 million to Hamas, the terror group that rules the Gaza Strip and has vowed Israel’s destruction.

Before her defeat in the impeachment process, Rousseff ignited an unprecedented diplomatic standoff with Israel, when the Brazilian government remained silent for several months to signal an official rejection of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s pick for ambassador in Brasilia. Dani Dayan, who once chaired the settler movement in Israel, ended up heading the Israeli consulate in New York.

“Bolsonaro stood out among the many candidates for including the State of Israel in the major speeches he made during the campaign,” Israel’s honorary consul in Rio, Osias Wurman, told JTA. “He is a lover of the people and the State of Israel.”

Others say his right-wing appeals are misunderstood.

“There is a myth that being a rightist is bad because Brazilian history books have always associated the right with the military regime, as well as Nazism and fascism. It’s not true,” said Felipe da Costa, who co-founded the Jewish youth movement Betar in Rio and manages Amigos, a Facebook group where political debates around Jewish subjects are abundant. “Israel, for instance, is a great example where rightists and leftists work together and alternatively. That’s one of the reasons of the country’s success.”

Leftist Jewish groups and many moderates accuse Bolsonaro of racism, homophobia and misogyny. Anti-Bolsonaro demonstrations have been held in some cities, while groups and hashtags against the candidate have appeared online. Bolsonaro has said that he is “pro-torture,” joked about rape with a female lawmaker and said he would rather see his son die than be homosexual, among other things.

“It’s not about what I think; the facts are there,” the leftist Jewish activist Mauro Nadvorny told JTA. “Bolsonaro hailed Carlos Brilhante Ustra [a notorious military leader from the dictatorship period], who tortured mothers by putting rats inside their vaginas while their children watched them. Jews cannot say they’ve never known.”

Living in Israel since March, Nadvorny created the Facebook group called Judeus contra Bolsonaro, or Jews against Bolsonaro, which has 8,000 members.

“Many Jews were tortured and killed during the Brazilian dictatorship not only because they were left-wingers, but also because they were Jews, they were always reminded of that,” Nadvorny said. “When Hitler wrote ‘Mein Kampf,’ he didn’t say he would murder 6 million Jews and many Jews voted for Hitler over a better Germany.”

The harsh treatment of Jewish leftists under the military dictatorships was a subject of a symposium at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2014.

Guilherme Cohen, a prominent new young Jewish leader, co-led an event at the ASA Jewish association in Rio on Oct. 23 featuring Haddad. Several Jewish and non-Jewish leaders and artists were among an audience of some 300, according to the organizers.

“The Jewish community is divided,” said Cohen, who is affiliated with the PSOL political party, which has an openly anti-Israel platform. “On the one hand [are] those who applaud the hate speech, violent and criminal, of a candidate who has no appreciation for democracy. On the other hand are those who applaud the speech of democracy, affection and empathy.”

In 2017, three leftist Jewish youth movements refused to attend Brazil’s longest running Israeli dance festival to protest Bolsonaro’s appearance earlier that year at a mainstream Jewish center. The protest split Brazilian Jews between leftists who wanted Bolsonaro treated as a pariah and a mainstream that wanted to encourage a candidate who told his Jewish audience that his heart bleeds “green, yellow, blue and white,” the colors of the Israeli and Brazilian flags.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.