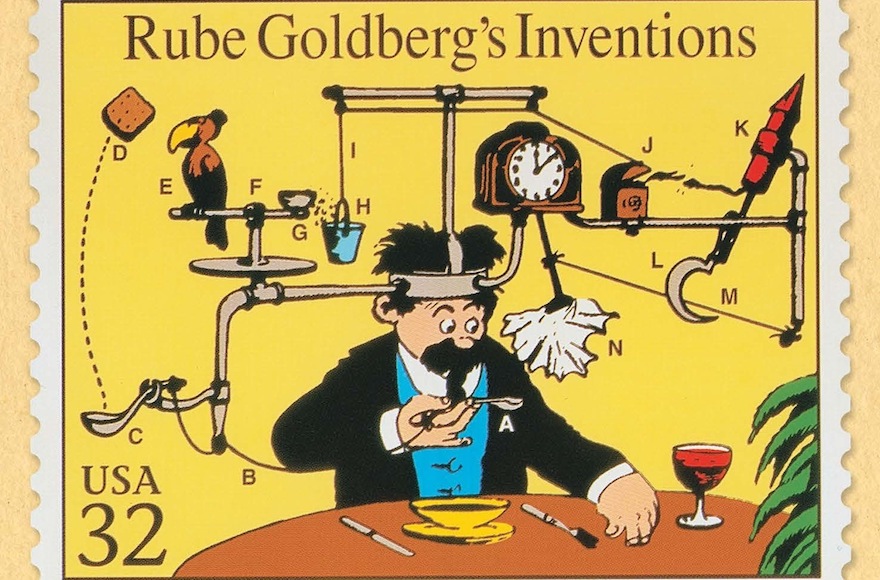

(JTA) — When one hears the name Rube Goldberg, one concept instantly comes to mind: those fun machines that complete simple tasks in overly complicated and humorous ways. Think a ball rolling down a long ramp that hits a series of dominoes, which hits something else, so on and so on.

Nearly 50 years after his death, his name will come up in politics or another field to explain something that’s unnecessarily complex. Cartoonist Art Spiegelman, best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel “Maus,” once said that “Rube Goldberg knew how to get from A to B using all the letters in the alphabet.”

But as an exhibit at the National Museum of American Jewish History points out, there was a lot more to Rube Goldberg than the machines he drew.

Goldberg, who was born in 1883 and died in 1970, also was an extremely prolific editorial cartoonist, as well as an inventor, engineer, humorist and author. He even had stints in the advertising industry and in Hollywood in a career that spanned over 70 years. He won a Pulitzer in 1948 for his political cartoons, and is an enduring inspiration to children in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields, where his creations are still used in lessons.

Rube Goldberg’s cartoons were not all of complicated contraptions. Above is a collage he drew on the day of his 1916 wedding to his bride Irma. (Rube Goldberg Inc.)

Goldberg’s complete life and work is the subject of “The Art of Rube Goldberg,” an exhibition that opened last week and runs through Jan. 21 at the Philadelphia museum. The exhibit, which follows stops at museums in San Francisco and Chicago but features some new items, is the first major exhibition of Goldberg’s work since the Smithsonian presented one shortly before his death.

“The Art of Rube Goldberg” consists of machines and cartoons, as well as artifacts from Goldberg’s life. Included are numerous editorial and political cartoons — on topics ranging from government austerity measures to the continual struggle for peace between Jews and Arabs — that wouldn’t be out of place today.

As an editorial cartoonist for papers such as the San Francisco Bulletin and the New York Evening Mail, Goldberg even waded into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as an example one view at the National Museum of American Jewish History shows. (Stephen Silver)

Goldberg, in fact, drew an estimated 50,000 cartoons in his career, but only a small fraction of them were related to his eponymous machines, his granddaughter Jennifer George said. He drew for papers such as the San Francisco Bulletin and the New York Evening Mail, where his strips were introduced to the masses through McClure, the country’s first newspaper syndicate. He started the machine drawings in the late 1920s in one of his several syndicated series — one involving a character named Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts.

The exhibit, supervised in Philadelphia by chief curator Josh Pearlman, is presented with the cooperation of two of of Goldberg’s grandchildren — George and her cousin, John George, both children of Goldberg’s sons. The two sons, Thomas and George, changed their surname to George at the insistence of their father (yes, one became George George). He claimed that it was for their safety because he received copious amounts of hate mail for his political cartoons, but there is debate within the family over whether the name’s obvious Jewishness had anything to do with it. Goldberg was the son of Jewish parents in San Francisco and lived through a time of harsh anti-Semitism before the world wars.

The exhibition also includes more personal, never-before-seen items, such as a cigar box belonging to Goldberg’s father. There’s a video installation showing modern-day movies — from Wes Anderson flicks to Wallace and Gromit tales to “Pee Wee’s Big Adventure” — that have all used Rube Goldberg-like concepts.

A wall at the exhibit at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia features a typically complex Rube Goldberg machine. (Stephen Silver)

Also new is a Forbes magazine cover drawn by Goldberg from 1967 that looked at “the future of home entertainment.” It was tracked down recently by the daughter of a former Forbes art director and lent to the exhibit.

Goldberg died when Jennifer George was 11 years old, but she is the primary custodian of Goldberg’s intellectual property and legacy.

The exhibit in Philadelphia features Rube Goldberg on a poster by the Pathé news agency calling him the “World’s most famous Newspaper Cartoonist.” (Stephen Silver)

“I remember him through the lens of a child. But when carrying on the legacy of Rube fell into my lap when my dad died, over a decade ago … I really had to do some heavy lifting,” she said. “All of the cartoons that had once been on the walls of the den in the house that I grew up in, and in our grandparents’ study, which I had never read, suddenly I had to start reading them, and I had to start educating myself as to who Rube Goldberg was, through the lens of an adult, at least if I was going to do this correctly.”

Several events related to the exhibit are planned, including a Rube Goldberg Machine Contest for local high school students. Admission to the exhibition will be free on Election Day, Nov. 6.

“We are preparing for a lot of serious and zany fun,” Ivy Barsky, the museum’s CEO, said at the press preview last week. “Which we don’t get to say a lot at a history museum.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.