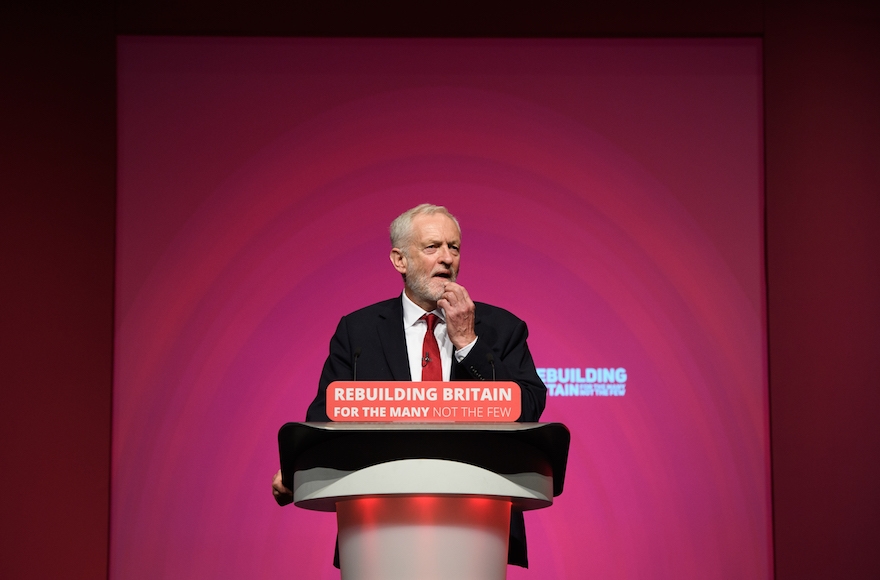

(JTA) — Steeped in anti-Semitism accusations involving him and his supporters, British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has made many Jewish enemies — including inside his own party.

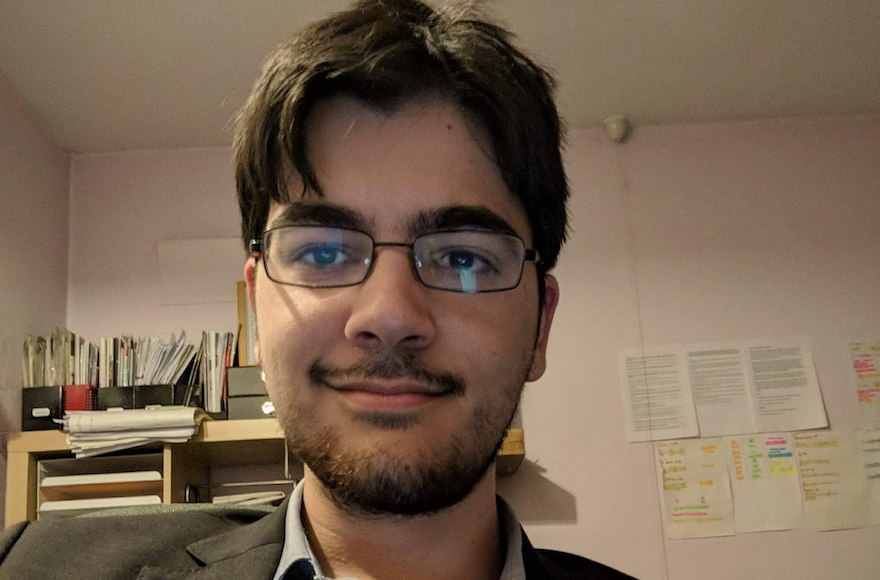

But one of his most effective critics is not Jewish. He is a meteorology student at the University of Reading who describes himself as “just a kid with a laptop.”

Denny Taylor, 20, has used that laptop to keep a running tally of party members who have flouted Labour’s own guidelines against hate speech and report them to the party’s ethics review panel.

Horrified at the revelations about Corbyn’s ties to anti-Semites, Taylor set up Labour Against Anti-Semitism, or LAAS, in 2016 with a few dozen non-Jewish and Jewish volunteers. He was 18 and had voted the previous year for Corbyn.

It was LAAS that last month reported to Labour’s ethics panel on an old recording in which Corbyn declared that Zionists “don’t understand English irony.” The group has flagged 1,200 alleged members who it said have breached the party’s guidelines against hate speech and has a backlog of about 2,000 additional cases of people engaging in what LAAS considers anti-Semitic rhetoric. LAAS has not reported the latter yet, according to its spokesman, Euan Philipps, who also is not Jewish.

LAAS “punches far above its weight,” said Jonathan Hoffman, a British Jew who has been involved in some of the most vocal protests against Labour’s anti-Semitism problem — including a poster campaign in London earlier this year.

The “small group of volunteers,” to which Hoffman does not belong, “has achieved great success in raising the profile of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party, and is now the first port of call for media like the BBC, The Times and Sky News,” he told JTA.

Corbyn, a far-left politician who was elected to lead Labour in 2015, has alternated between vowing to address Jewish concerns and dismissing them. In August, he called many Jews’ existential fears about a Corbyn-led government “overheated rhetoric.”

He also has refused to apologize for his own controversial actions, including his honoring in 2015 of dead Palestinian terrorists and saying in 2013 that local “Zionists” lack a sense of irony.

Amid attacks by Labour moderates, Corbyn’s worsening relationship with British Jewry sunk to a new low in August when former chief rabbi Jonathan Sacks, a lord and probably British Jewry’s most eminent representative, called Corbyn “an anti-Semite.” The Jewish Labour Movement, a group of coreligionists within the party that once was British Jewry’s political home, has threatened to sue Corbyn and dismissed his promises to fight anti-Semitism as lip service.

Corbyn supporters dismiss many critics either as “Zionists” — Corbyn himself has acknowledged that the term has often been “hijacked” by anti-Semites as code for Jews — or Labour rivals seeking to weaponize anti-Semitism claims.

Such criticism is harder to pin on LAAS, according to Taylor.

Beyond having non-Jewish members from across the political spectrum within Labour, “We primarily file complaints that are well-documented,” Taylor said. He traces his commitment to fighting anti-Semitism within Labour to a desire to “make up for the damage” that Corbyn and other of his erstwhile supporters helped cause to the United Kingdom.

The ethics board of Labour — a party eager to shake off its image as a hub for anti-Semitism — is forced to act on the complaints on Corbyn’s behalf, making the complaints and subsequent disciplinary actions more difficult for his supporters to dismiss than an external criticism.

Denny Taylor founded the group Labour Against Anti-Semitism when he was 18. (Courtesy of Taylor)

LAAS said it follows Labour’s own definition of anti-Semitic hate speech, which as of last month is identical to that of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. That working definition acknowledges that criticism of Israel is not automatically anti-Semitism, but also notes examples of how anti-Israel and anti-Zionist rhetoric often takes anti-Semitic forms.

Among LAAS’s recent successes is the April suspension of Pam Bromley, a local lawmaker from northern England. LAAS reported her 2017 Facebook post defending her opposition to the Rothschilds, the famous Jewish banking family at the center of numerous anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. She urged followers to remember that the “Rothschilds are a powerful family (like the Medicis) and represent capitalism and big business — even if the Nazis DID use the activities of the Rothschilds in their anti-Semitic propaganda. We must not obscure the truth with the need to be tactful.”

Another subject of an LAAS ethics complaint is Anne Kennedy, who was suspended in May for writing that Israeli Jews are “Hitler’s bastard sons.”

Jane Dipple, a university lecturer in media and communication, was suspended and possibly fired for inveighing against “a Zionist attempt at creating a pure race” and “rampant Zionism across the media” in a post that included a link to an article on the neo-Nazi website Daily Stormer. It was headlined “BBC to Replace Male Jew Political Editor with Female Jew.”

This kind of rhetoric is something that Emma Feltham, a London painter-decorator and longtime Labour voter, had never imagined existed in mainstream politics before it surfaced in 2015, after thousands of far-left voters entered Labour in support of Corbyn.

“I’m a white English person; I had never seen anything like this. I remember crying the first time I did,” recalled Feltham, who joined LAAS following that experience.

The fact that she’s not Jewish, she said, makes it harder to dismiss her criticism.

“It’s harder to ignore, they can’t say, ‘oh, it’s just because she’s a Zionist, what she says doesn’t matter because she’s Jewish,’” Feltham said.

When rank-and-file non-Jewish members of Labour fight in the trenches against anti-Semitism, she said, “it shows there are people out there who care, who find if unacceptable.”

Nevertheless, Labour’s highly public anti-Semitism problem seems to have only marginally hurt the party’s popularity in the general population. Corbyn’s approval rating in a YouGov poll from Sept. 27 was 10 points higher than in a poll conducted on that week in 2016. (He currently enjoys 51 percent approval versus 49 percent disapproval.)

Anti-Semitism isn’t even the main issue working against Corbyn, according to Taylor.

“The main issue is Corbyn’s handling of Brexit,” he said. Critics say the Labour leader has failed to effectively oppose the government’s policy of exiting the European Union.

With positive ratings and a Conservative government in shambles over internal disagreements on Brexit, Corbyn seems nearer than ever to becoming prime minister, regardless of his being pummeled on the front pages of mainstream dailies over Labour’s anti-Semitism problem.

Given this reality, Feltham said she understands and agrees with British Jews who say they view a Labour government led by Corbyn as an existential threat to their community — a statement that, unprecedentedly, all three major British Jewish newspapers put on their front pages in July, and which the Board of Deputies of British Jews has also echoed.

“I don’t think it’s an overreaction,” she said of this warning. And Feltham believes that a “party that can target one minority or group will target others when it becomes expedient. It’s a danger to society at large.”

Still, Feltham, Taylor and Philipps, the LAAS spokesman, said they are not sure whether they can win the fight for Labour’s identity and image.

“This question is beyond my control,” Feltham said. “All I know is I can’t stop fighting. I don’t want to have to say that I did nothing when all of this was happening.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.