A friend of mine recently filled in at his Conservative shul for a Torah reader who had suddenly taken ill on Friday night. He chanted the entire portion with just a couple of hours of practice. I was standing next to him at the kiddush after services when congregants came up to express amazement at this feat. He pointed to me and said, “Ted could have done it just as easily.” I stared at him. “No,” I said. “It would have taken me at least a couple of weeks to learn that.” It felt liberating to confess it.

Ask any professor what he or she has nightmares about and you will hear that they dream, especially right before the beginning of the school year, about coming into class without their lecture notes and being exposed as incompetent. Last year, I started a new job as the executive director of a synagogue; hired just before the High Holy Days and faced with an overwhelming to-do list, I used as my mantra, “Fake it till you make it.” Rabbis, Jewish educators and Jewish communal professionals are not immune from pretending to a level of Jewish knowledge that they may aspire to, but do not possess. Men may be especially reluctant to admit that they are out of their depth — the reason that the Israelites got lost for 40 years in the desert, as the old joke goes, is because Moses didn’t want to ask for directions!

All of us are playing a role to some extent, in putting ourselves forth in public. Perhaps this is why our society is obsessed with imposters and con artists, and has been since at least the 19th century. As Karen Halttunen theorized in “Confidence Men and Painted Women,” her seminal 1982 study of middle-class mores during the age of industrialization and urbanization in America, the con man symbolized the transformation from an agrarian society in which everyone knew others in their community, to one in which people were brought into daily contact with total strangers whose motivations were unknown and often suspect.

Nowadays, witness the popularity of such films about con artists as “Ocean’s 8,” this summer’s new, all-female extension of the “Ocean’s 11” series. Jewish con men are particularly visible in our popular culture; witness Barry Levinson’s HBO film, “The Wizard of Lies,” starring Robert DeNiro as Bernie Madoff, which premiered last summer. And as veteran political reporter Walter Shapiro writes in his 2016 page-turner, “Hustling Hitler: The Jewish Vaudevillian Who Fooled the Führer,” the author’s great-uncle, Freeman Bernstein, was a colorful Jewish impresario, card shark and vaudeville producer who was paid $2 million by the Nazis for Canadian nickel that they needed to line their guns; he shipped them rusted car parts and tin cans instead.

Frank Rich expounded upon the phenomenon in “American Pseudo,” his masterful New York Times Magazine essay on the 1999 Anthony Minghella film, “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (based on the 1955 Patricia Highsmith novel), about Tom Ripley (Matt Damon), a young Princeton graduate from a working-class background who assumes the identity of a wealthy classmate, Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law). Rich links the film to psychoanalyst Robert Jay Lifton’s idea of the “protean self” and the peculiarly American desire and capacity for reinvention. Ripley, whom Rich compares to a more famous (and quite possibly Jewish) fictional character, Jay Gatsby, stands for all of us in our desire to be other than what we are, to remake ourselves in the image of those whom we admire.

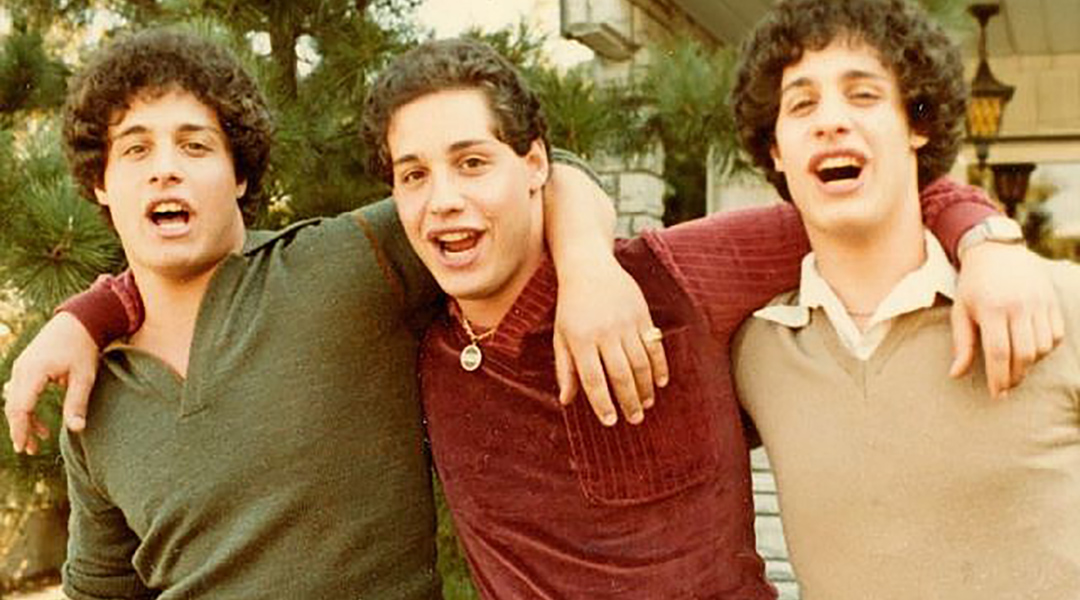

“Three Identical Strangers” is Tim Wardle’s fascinating new documentary about a set of New York Jewish triplets (founders of the raucous Soho restaurant, Triplets Roumanian Steak House, that closed in 2000), who grew up not knowing of each other’s existence. The film opens with one of the brothers, Bobby Shafran, going off to community college in the Catskills and initially being mistaken for his brother, Eddy Galland, who had been a student there the previous year. (The third brother, David Kellman, is discovered as a result of the publicity surrounding the meeting of the first two.)

Bobby’s unintentionally impersonating his brother leads to the brothers being reunited, but before long, Eddy, who has no health insurance, returns the favor by deliberately pretending to be Bobby in order to have his appendix removed. Through an initial focus on mistaken identity, the film goes to a much darker place and raises questions about the nature of identity itself, where it comes from (nature or nurture) and what it means.

As Rosh HaShanah approaches, my New Year’s resolution is to be honest about not knowing all the answers, even when it comes to Jewish things that I think that I should know. After all, as a British spy quips in “The Constant Gardener,” Fernando Meirelles’ 2005 thriller, “Only God knows everything, and He works for Mossad.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.