(JTA) — When Aviva Schwartz started praying publicly for Palestinians at her Jewish summer camp, she knew it would be controversial.

Schwartz had grown up ensconced in the Conservative movement, had attended three of its Ramah camps and had moved up the ranks as a staff member at Ramah Wisconsin. When Israel’s war in Gaza broke out in the summer of 2014, she was the unit head for incoming seventh-graders — a position reserved for staff veterans.

She was also a college student who, after a lifetime of pro-Israel education, was becoming more critical of Israel’s control of the West Bank and its treatment of Palestinians. So when fellow staff members began saying Kaddish, the mourners’ prayer, for Israelis killed in the conflict, she began praying for Palestinian victims as well.

Her superiors let her do it — but they did not back her up when she felt backlash from her unit counselors.

“I felt pretty strongly that we needed to acknowledge and remember the lives of Palestinians and Israelis,” Schwartz said. “Particularly, Israeli staff were incredibly upset and uncomfortable. I wasn’t told not to do that, and I don’t feel like I was really given support in the form of the camp backing me, to support me in my conversations with upset counselors.”

Now, with tensions in Gaza again running high, Schwartz wants to help other Jewish camp counselors do what she did: talk about Palestinian narratives and challenge Israeli actions while at camp. She was among the organizers of a daylong training for counselors on how to discuss the issue with campers and staff, both informally and in camp programs. The goal is to encourage counselors to present divergent sides of the conflict rather than solely a pro-Israel line.

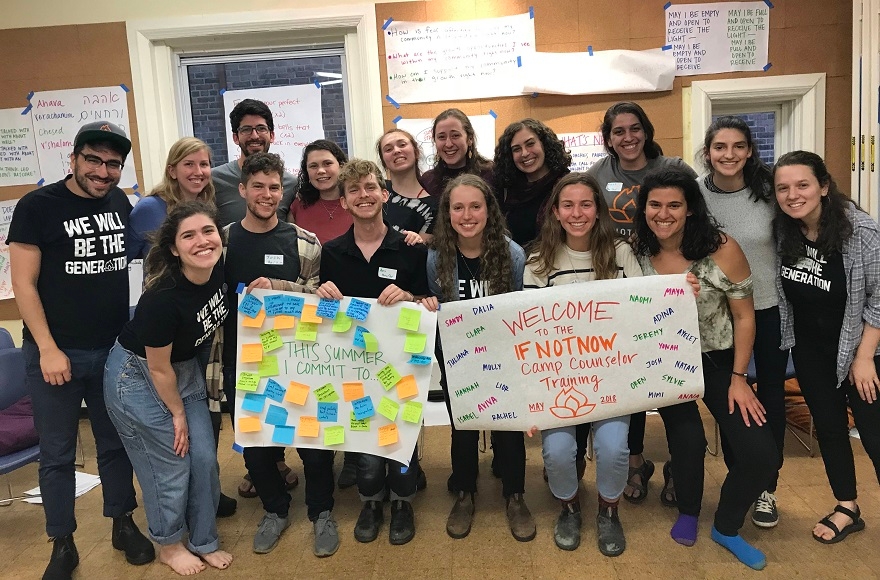

The May 27 session in Boston attracted about a dozen counselors from eight Reform, Conservative and liberal Zionist camps. It was run by IfNotNow, a group of young Jews that opposes Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and American Jewish support of it.

“Having to relearn and re-evaluate your whole childhood and mentorship and teaching because of the feeling of being lied to is a potentially life-shattering moment,” said Schwartz, now an employee of the campus group Hillel at the University of Washington. “I don’t want campers to have to think, oh, did my counselors know the occupation is happening and they’re just lying about it?”

It’s a change of pace for IfNotNow, which focuses much of its energy on public and often disruptive protests of large American Jewish organizations. But in March, members of IfNotNow met with Mitchell Cohen, the national director of Ramah camps, to outline their concerns with what they feel is an overly one-sided Israel curriculum at the camps.

Cohen proudly acknowledged that Israel is portrayed in a positive light at the camps. Ramah, like other Jewish camps, infuses Israeli culture into much of its programming. Campers study Hebrew daily, perform Israeli dances, sing Israeli songs, eat Israeli food and learn about the country’s history. Delegations of Israeli counselors and staff work at all of the camps, whose founding was inspired partly by the ethos of early 20th-century labor Zionism.

Several Ramah staffers attended the training. But Cohen said he wasn’t worried about what they discussed and is open to nuanced Israel education — though any educational program counselors put on this summer will, like all others, have to be vetted by their camps’ senior staff.

“Some people use the word occupation in quite harsh ways,” he said. “Some people use it in more mild ways. Certainly the fact that there is a difficult situation between the Israeli and Palestinian peoples, a conflict, people suffering on all sides — this is something we don’t have a problem talking about at camp.”

Cohen said the camps’ top priority is fostering a sense of affection in campers toward Israel as a Jewish homeland. He noted that a range of perspectives exist within Israel regarding the conflict, but there are red lines.

“To the extent that there are liberal opinions that are critical of Israel that are not Zionist, anti-Zionist, we would never allow that at camp,” he said. “First we teach a love for Israel. Then we teach the nuances and the conflict.”

Noam Weissman, who is consulting with a Jewish camp on its Israel curriculum, also says an Israel curriculum should combine love and nuance. Weissman, senior vice president for education for Jerusalem U, a video-focused Israel education organization, says kids need to learn about the diversity and complexity of Israel, but from a place of love.

Loving Israel, he said, “builds in a real confidence of Jewish peoplehood, a love for oneself and a confidence for oneself.”

“We want to be able to ask tough questions, but we want to do it in a contextualized way that says we love Israel, we care about Israel,” Weissman said. “The occupation needs to be discussed and the different perspectives on the occupation need to be discussed, but the foregone conclusion that the occupation is ‘bad’ is indoctrination just like anything else that they’re claiming is indoctrination.”

Weissman was referring to claims by some Jewish critics that the “pro-Israel” approach is also indoctrination, and that Israel advocacy groups only discuss the Palestinian side in order to debunk it.

At the IfNotNow training, participants began by talking about their camps and why they feel attached to them. Following seminars on the history of American Jewish camps and IfNotNow’s activism, participants discussed how to talk about difficult issues with children. After brainstorming ideas of how they would discuss the conflict with their campers, the participants saw a presentation by counselors from Habonim Dror, the liberal Zionist youth movement, about their curriculum on Israel and the Palestinians.

Adina Alpert, a lifelong camper at Ramah in Ojai, California, who co-organized the training, said the event was coming from a positive place: The counselors do not want to hurt their camps, even if they were unhappy with some of the Israel education they received there. Alpert fondly recalled a wealth of Israeli cultural programs at camp. But she also felt that lessons on Israeli history, the Israeli War of Independence and subsequent events did not present the Palestinian point of view.

“These are not communities we want to be leaving or alienating or becoming isolated from,” she said. “We want to do this work within our communities because we love our communal moments of joy and growth [while] thinking back and reflecting on the moments where our Israel education wasn’t what we wanted it to be.”

A participant at the IfNotNow session makes a point. (IfNotNow)

But ahead of the conference, counselors were not exactly sure what their ideal Israeli-Palestinian program would look like. Some suggested having campers read Palestinian stories or poems, or see Palestinian artwork. Others suggested studying Palestinian texts or having a Shabbat program framed around the Palestinian experience. Another idea was to have campers read a number of opinions and perspectives regarding a recent event in the region, like the recent clashes on the Gaza border.

Alpert said “if campers hear the term ‘Palestinian’ in a non-derogatory way, that would be a success.”

Maya Seckler, an incoming gardening counselor at the Reform Eisner Camp in Massachusetts, wants to expose her campers to Palestinian life by placing signs next to each vegetable with its name in Hebrew, English and Arabic.

“I want to expose kids to Arabic and Palestinian culture,” she said. “That’s part of Israeli culture, that all three languages are going to be on every sign, and it’s not ignoring a whole group of people in Israeli history and Israeli culture. Both are valid and both are important.

An incoming unit head at Ramah Outdoor Adventure in Colorado, Sylvie Rosen, said she has not formulated programs yet for her campers because she wants to talk first to her counselor staff. But if violence flares up in Israel this summer, she does not want to shy away from it.

“Going into ninth grade, I think they’re old enough to hear stories from families living in the West Bank, living in Gaza,” she said. “If the violence in Gaza continues throughout the summer, that’s something I want to address.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.