NEW YORK (JTA) — The Torah tells how God created the earth and the heavens, although the stories that follow tell us more about the former than the latter. A new exhibit doesn’t quite answer theological questions about space, but it does show the ways in which Jews have looked at, written about and traveled into the final frontier.

“Jews in Space: Members of the Tribe in Orbit,” named after a Mel Brooks gag, is an exhibit organized and on view at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Center for Jewish History here. It features both Yiddish and Hebrew books on astronomy and astrology, science fiction works created by Jews and sections on the history of Jewish astronauts.

JTA was given a tour by Eddy Portnoy, YIVO’s senior researcher and director of exhibitions, who curated the collection with Melanie Meyers, and learned about some of the unusual and unexpected relationship between Jews and the cosmos.

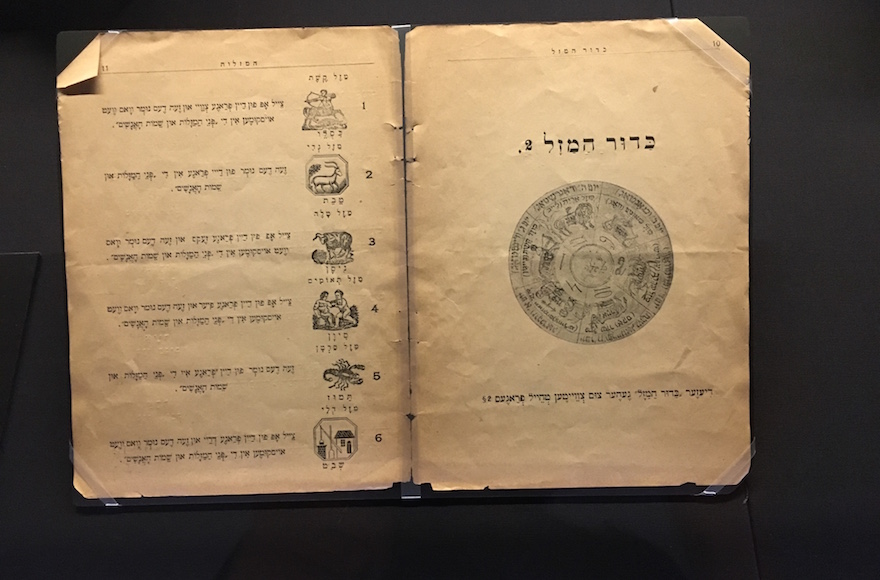

This book of horoscopes was written in Yiddish.

A book from 1907 featured in the YIVO exhibit “Jews in Space” contains horoscopes in Yiddish. (Josefin Dolsten)

Published in 1907 in Odessa, Ukraine, “The Revealer of That Which Is Hidden: A New Practical Book of Fate” gave Yiddish readers a way to learn about their futures by way of astrology. Much like a modern-day horoscope, the book offered predictions based on the reader’s zodiac sign. Similar books existed both in Yiddish and Hebrew during the time period, but rabbinic authorities were not thrilled, since astrology is banned by Jewish law (although zodiac symbols have shown up as synagogue decorations for at least 1,500 years). Despite that, Jews at the time continued to read horoscopes as well as seek other ways of predicting the future, such as by going to psychics and reading tea leaves.

The first Jewish American to go into space was a woman.

Mission specialist Judith Resnik sending a message to her father from on board the shuttle Discovery on its maiden voyage, Aug. 30, 1984. (NASA/Space Frontiers/Getty Images)

Judith Resnik became the first Jewish American and second Jew (Soviet astronaut Boris Volynov was the first) to go into space when she flew on the maiden voyage of the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1984. Born in 1949 to Jewish immigrants from Ukraine who settled in Ohio, Resnik worked as an engineer at the Xerox Corp. before being recruited to NASA in a program to diversify its workforce. Resnik was only the fourth female to ever do so. She died in 1986 along with the rest of the crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger when the spacecraft broke apart shortly after takeoff.

In 1985, a Jewish-American astronaut read from the Torah in space.

Jeffrey Hoffman in 1985, the year he went on a NASA mission into space and read a Torah portion. (NASA/Wikimedia Commons)

Jeffrey Hoffman, the first Jewish-American man to go into space, consulted a rabbi on how to observe Judaism on his first trip, in 1985. Hoffman, a Brooklyn native who was born in 1944, brought with him a scaled-down Torah and did the first Torah reading outside of Earth. He also had a set of Jewish ritual items specially made for his trip, including a mezuzah with a Velcro strip that he would attach to his bunk and a prayer shawl with weights to keep it from floating away in zero-gravity. He also brought a menorah to celebrate Hanukkah, although he was never able to actually light it aboard the spacecraft.

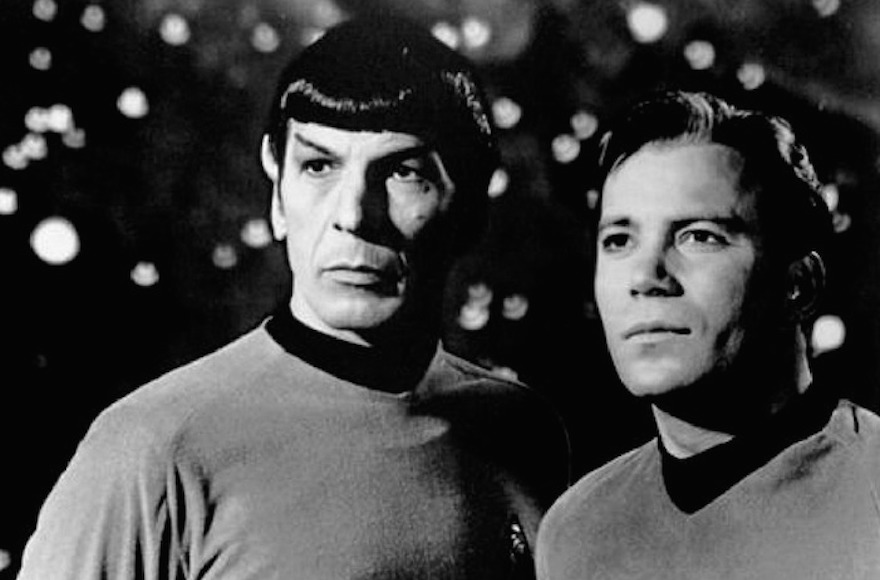

The Vulcan salute on “Star Trek” has Jewish origins.

Leonard Nimoy, left, as Spock on “Star Trek,” alongside co-star William Shatner. (Pixabay)

Actor Leonard Nimoy used an unlikely source of inspiration for his character Spock’s iconic Vulcan salute, which consists of a raised hand with the middle and ring fingers parted into a V. The gesture looks just like the one kohanim do in synagogue during the Priestly Blessing. In his autobiography, Nimoy explained that he had copied the Jewish gesture, which he had seen in a synagogue as a child (it also appears on tombstones of kohanim). The Vulcan salute, which is accompanied by the phrase “Live long and prosper” (the kohanim’s blessing begins “May God bless you and guard you”), became so iconic that the White House mentioned it in a statement issued on Nimoy’s death in 2015.

An alien in “Futurama” was named after the YIVO Institute.

Yivo was a many-limbed, sex-craved character a decade ago on the animated comedy. (Screenshot from YouTube)

Some might think it a coincidence that the institute shares a name with a bizarre extraterrestrial in the animated science fiction comedy series. In a 2008 direct-to-video film based on the TV series, Yivo (voiced by actor David Cross, who was raised Jewish) is a tentacled being who uses his many limbs to have sex with every living being in the universe. Turns out the screenwriter, Eric Kaplan, is friends with Cecile Kuznitz, a professor at Bard College who has done extensive research on the institute. He decided to, um, honor her by naming the character after the topic of her work, the archive and research center on Eastern European Jewish life founded in Vilna in 1925.

A Jewish immigrant to the U.S. helped popularize science fiction.

Hugo Gernsback founded the science fiction magazine “Amazing Stories” in 1926. (Courtesy of YIVO Institute for Jewish Studies)

Hugo Gernsback, a Jewish immigrant from Luxembourg, is sometimes called “The Father of Science Fiction” for publishing a magazine that helped popularize the genre. Launched in 1926, “Amazing Stories” featured tales of aliens, robots and other beings, including ones written by Gernsback himself. His magazine brought science fiction — a term he coined — to the mainstream and inspired many writers, such as Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the Jewish-American duo that created Superman. Gernsback left “Amazing Stories” in 1929, although it held on in one form or another until 2005. Among the Jewish writers who had their first stories published in the magazine were Isaac Asimov and Howard Fast.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.