This story is sponsored by the Orthodox Union.

Erik Bittner can pinpoint the exact moment he felt his son with autism was truly included at his family’s Orthodox synagogue, Shaarei Tefillah in Newton, Massachusetts. It was a Shabbat morning and the gabbai – the sexton orchestrating services — called Bittner’s 24-year-old son, Nathan, up for an aliyah, to recite the blessings over the Torah.

“Nathan whizzed through the brachot and he was effusive in his gratitude for going up there,” Bittner recalled, using the Hebrew word for blessings. “He shook everyone’s hand. It was a touching emotional moment.”

But the next week when Nathan showed up late and afterward asked why he didn’t get an aliyah, the gabbai responded: “I only give aliyahs to people who show up on time.”

Bittner wasn’t upset; on the contrary. He was pleased his son was treated like anybody else.

“Real inclusion means those with special needs are held to the same standards as everyone else — as long as those standards do not exclude them,” Bittner said.

The episode is a sign of the changes beginning to take place in many Orthodox synagogues, where communities are going to greater-than-ever lengths to be more inclusive of Jews with disabilities. The changes, both cultural and physical, are transforming congregations that traditionally have been slower to adapt than those affiliated with more liberal Jewish denominations.

Orthodox shuls are now installing wheelchair-friendly ramps to bimah platforms, providing large-print or Braille prayer books for the visually impaired, bringing in ASL interpreters for the deaf and offering inclusive programming for kids with physical and developmental disabilities.

At Lincoln Square Synagogue in Manhattan, which moved into its new, fully accessible building in 2013, the congregation provides ASL for events upon advance request and on Purim has run programs for those with sensitivity to noise.

In Los Angeles, B’nai David-Judea, which long has had bimah ramps, recently added better signage and magnifying glasses for the visually impaired.It has a sign language interpreter available, and is discussing ways to make kids’ programming more inclusive of children with disabilities.

At the Young Israel of Hollis Hills-Windsor Park in Queens, New York, Rabbi Barry Kornblau permits service dogs in the synagogue sanctuary.

Beth Sholom Congregation in Potomac, Maryland, has ramps to the bimah from each side of the mechitzah barrier separating the men’s and women’s sections and holds an annual Disability Shabbat.

“It is a fundamental part of the Orthodox tradition that everybody should be welcome within the synagogue,” said Rabbi Judah Isaacs, the Orthodox Union’s director of community engagement. “There is a lot of recognition now that there are people with a wide range of disabilities, and rabbis want everyone to be part of the congregation and understand that we need to take an active role to make sure it happens.”

To help synagogues become more inclusive, the O.U.’s synagogue network of over 400 congregations across North America is working with Yachad-The National Jewish Council for Disabilities (an O.U. agency) and the Ruderman Family Foundation, which promotes inclusion in the Jewish community.

“We are changing the culture so that people with diverse abilities are given their rightful place within the Jewish community,” said Marla Rottenstreich, assistant director of Yachad, whose work includes advocacy, education and social programs for Jews with disabilities. “Over the last 10 to 20 years, Jewish values have evolved to adopt a more pro-disability attitude.”

Wheelchair-accessible bimah platforms, like this one at Young Israel of Toco Hills, in Atlanta, are among the changes Orthodox synagogues are making to be more inclusive of Jews with disabilities. (Courtesy of Young Israel of Toco Hills)

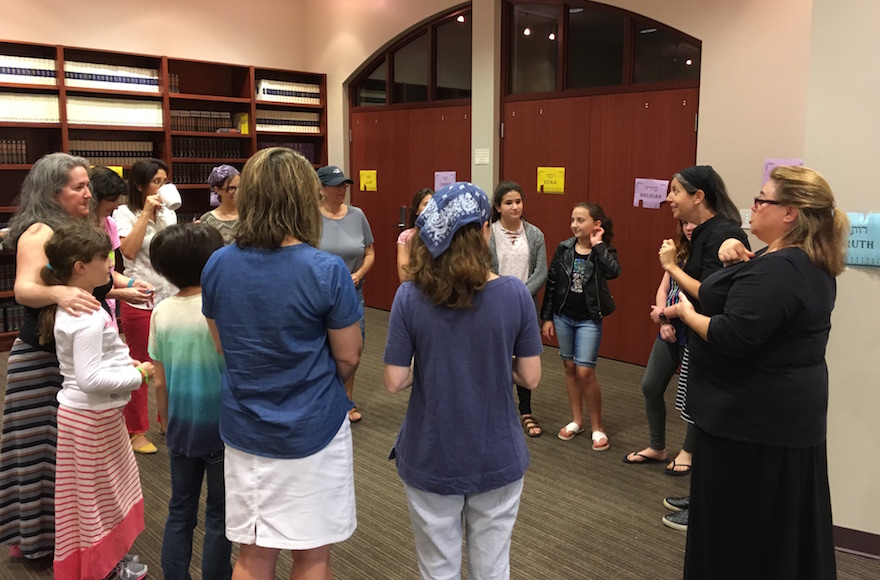

In the Boston area, the Ruderman Synagogue Inclusion Project, begun in 2013 in partnership with Boston’s Jewish federation, Combined Jewish Philanthropies, now provides 29 shuls with support to help people of all abilities feel valued and participate fully. Each participating synagogue has formed inclusion committees to oversee the process and tailor strategies to congregations’ individual needs.

“This project really gets the whole community involved in a way that is meaningful to them,” said Molly Silver, the project’s manager. “None of these inclusion plans are cookie-cutter because each of these congregations is so unique.”

Shaarei Tefillah was among the early participants. The shul has placed inclusion at the forefront of its building renovation plan, brought in a scholar-in-residence to offer sensitivity awareness training and has a rotating list of congregants who volunteer to push congregants in wheelchairs to and from synagogue. It offers programs to destigmatize mental illness and, in partnership with Yachad, hosts an annual Shabbaton focused on people with disabilities. The shul has been recognized by the O.U. as a Hineinu Synagogue — an exemplary national model of communal inclusiveness.

“Our goal is to be an inclusive community,” said the synagogue’s rabbi, Benjamin Samuels. “Inclusion takes hard work. Sensitivity and attunement to individual needs and communal needs requires a deft balance. We strive to continue to grow in our sensitivity to reach the maximum number of Jews to empower them to live as robustly Jewish lives as they can.”

In Atlanta, the Young Israel of Toco Hills made sure that its new building, completed in 2014, has wheelchair-accessible ramps and a special lowering mechanism so wheelchair-bound congregants can read an open Torah. The shul is also discussing ways to provide a quiet room for those with sensory issues.

“I believe the physical space of the synagogue building needs to be a reflection of our Jewish values,” said its rabbi, Adam Starr. “When a sanctuary has ramps, it sends the message from the moment you walk in that a synagogue is open to all.”

This year, the synagogue’s mother-daughter bat mitzvah program included a hearing-impaired mother who requested a sign interpreter for the class. The shul helped raise money for the interpreter.

The Hebrew Institute of Riverdale (also known as the Bayit) in the Bronx section of New York has bimah ramps from both sides of the mechitzah, a Shabbat elevator and a flexible sanctuary layout that permits chairs to be moved easily to make room for wheelchairs.

“Access is its own first barrier,” said Senior Rabbi Steven Exler, who credited the shul’s emeritus rabbi, Avi Weiss, with instituting many of the early accessibility changes. “We want everyone to feel like they belong without being aggressive about it.”

Through the Jewish Board of Children and Family Services, social workers in the synagogue are part of a clergy and programming team that helps serve members who have limitations. The synagogue also has a monthly program for people with mental or emotional challenges living in nearby group homes or residential treatment facilities.

Exler said the synagogue still has room for improvement. For example, the shul is grappling with how to help older members with hearing problems – a particular problem for Orthodox shuls, where the use of traditional microphones is prohibited on the Sabbath.

While many shuls may have trouble even constructing basic accessibility features, Bittner, of Shaarei Tefillah, says there are some steps any shul can take to become more inclusive — like warmly greeting someone with disabilities.

“Saying a few sentences makes a big difference, and you don’t need to build a ramp for that,” he said.

Regardless of the challenges, synagogues have a responsibility to be inclusive, said Jay Ruderman, president of the Ruderman Foundation.

“The synagogue is the central location for someone who chooses to practice their religion. When a synagogue takes an attitude that this isn’t the best place for you and your family — which is something I have heard over and over again — that doesn’t just turn people away from the synagogue, it turns them away from religion,” Ruderman said. “But if a rabbi takes the position that everyone has a place here, that is when you start to see changes.”

(This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Orthodox Union, the nation’s largest Orthodox Jewish umbrella organization, dedicated to engaging and strengthening the Jewish community, and to serving as the voice of Orthodox Judaism in North America. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.