NEW YORK (JTA) — Last month, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research made an astonishing announcement: the discovery of 170,000 Jewish documents thought to have been destroyed during the Holocaust.

The papers, which date from the mid-18th century through World War II, survived destruction attempts by both the Nazis and the Soviets.

In 1941, as part of program to loot Jewish museums and institutions, the Nazis raided YIVO, which is now based in New York but then was headquartered in Vilna. A group of Jewish slave laborers called the “Paper Brigade” smuggled some books, papers and artwork into the Vilna ghetto — risking their lives in the process. After World War II, a non-Jewish Lithuanian librarian, Antanas Ulpis, hid the collection in the basement of a church amid a campaign by the Soviet government to rid the country of religion.

In 1991, the Lithuanian government said it found 150,000 documents that Ulpis had kept in the church, but the new discovery appears to surpass that collection both in terms of size and the condition of the documents, said Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director.

Together the two discoveries make up “the largest collection of material about Jewish life in Eastern Europe that exists in the world,” Brent told JTA earlier this month at YIVO’s downtown headquarters here. Brent said the documents shed new light on the lives of Eastern European Jews, whose history is often told as a series of persecutions.

Jonathan Brent, the executive director of YIVO, says the documents help show a different side to Jewish life in Eastern Europe than what people tend to learn. (Josefin Dolsten)

“It was nothing but pogroms,” Brent recalled of being taught about Ashkenazi history as a child. “And what this opens up to is it was so much more than that, that indeed the Jews had a real civilization that flourished.”

The Lithuanian government found the documents in 2016 and told YIVO about them earlier this year. Most of the material remains in Lithuania, but 10 items are being shown through January at YIVO, which is working with the Lithuanian government to archive and digitize the collection.

Here is a look at a handful of the documents displayed at YIVO and what they teach about Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

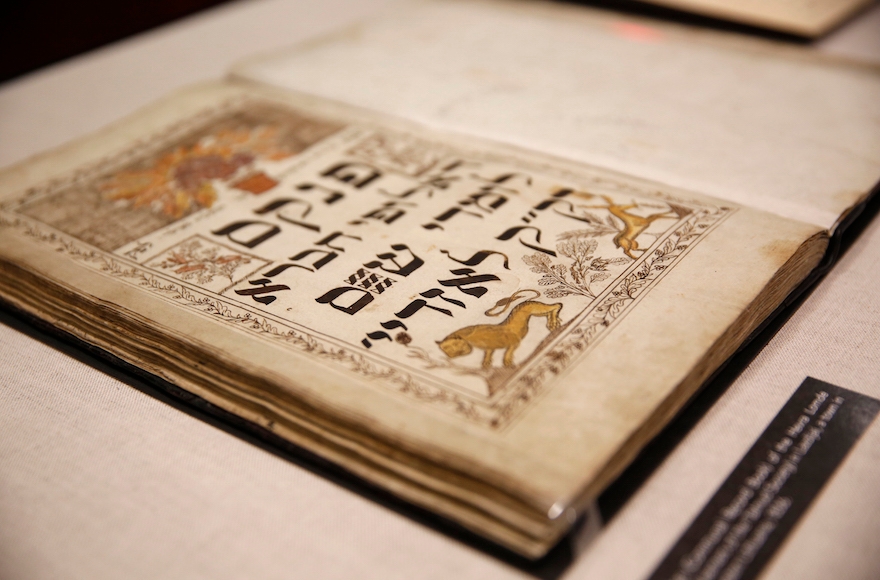

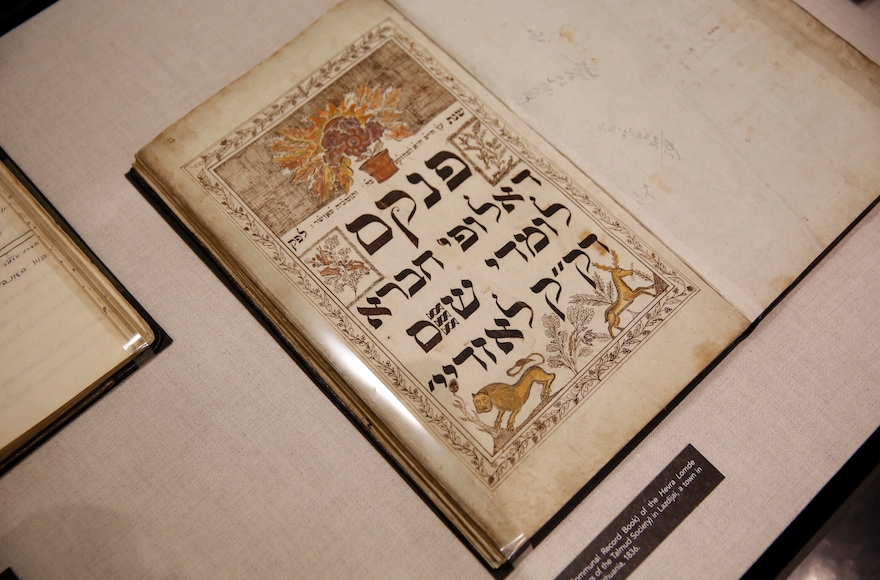

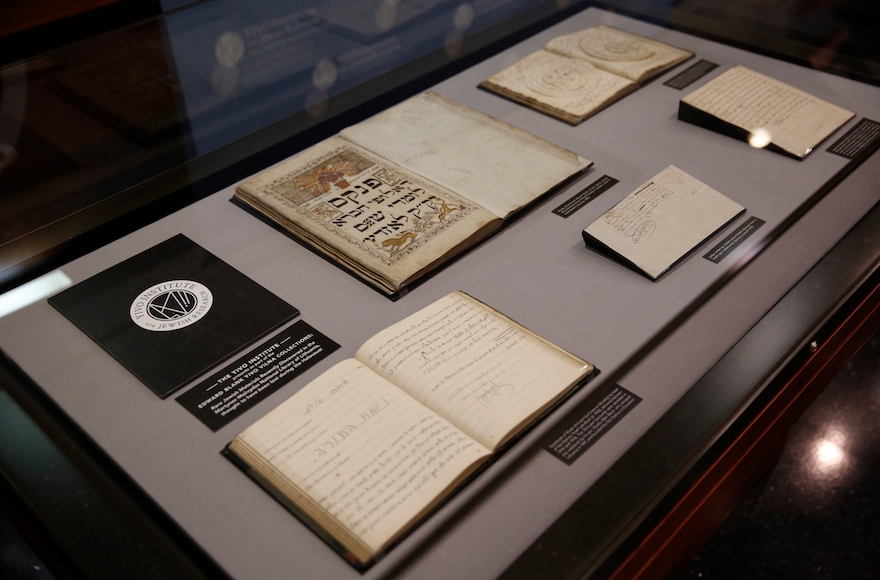

1. Communal record book, Lazdijai, Lithuania, 1836

This communal record books lists the regulations for being part of a Talmud study group in Lazdijai, Lithuania. (Thos Robinson/Getty Images for YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

The book, called a Pinkas, was written for a Talmud study association and used to record information about its members, such as births, deaths and business transactions. It is decorated with ornate illustrations and states that in order to be a part of the group, members must study a full page of Talmud together.

“What you see here in the way it’s decorated is the pride and the care that they felt about their life and their desire to memorialize it for generations,” Brent said.

2. Letter written by Sholem Aleichem from a health resort, Badenweiler, Germany, 1910

Sholem Aleichem wrote a letter, center in bottom row, from a health resort in Germany. (Thos Robinson/Getty Images for YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

The famed Yiddish author had health problems and would spend time in health resorts far away from friends and family. In this note, Sholem Aleichem makes fun of Leon Neustadt, a leader in the Warsaw Jewish community, writing that a biblical verse referring to non-kosher animals forbidden to Jews actually refers to Neustadt.

3. Agreement between a water carrier union and the Ramayles Yeshiva, Vilna, 1857

In the document, the group of carriers promises to donate a Torah scroll and raise money to purchase a Talmud set for the prominent yeshiva in exchange for using a room for religious services.

Water carriers, workers who ferried water to people’s homes, were “the lowest economic rung of society, and the fact they had a contract with the yeshiva was significant,” Brent said. “What this modest document shows us is that this community functioned in such a way that the very top of the community and the very bottom of the community communicated with each other and helped each other.”

4. 10 poems by Avrom Sutzkever, Vilna, 1943

The prominent Yiddish poet wrote these on top of old documents, creating a makeshift book for his poems in the Vilna ghetto, where paper was scarce. These are the earliest-known versions of the poems Sutzkever wrote in the Vilna ghetto, which he reproduced several times and knew by heart. He composed some of them while living in the woods as a partisan fighter. Writing the poems in the book helped give other ghetto residents greater access to them.

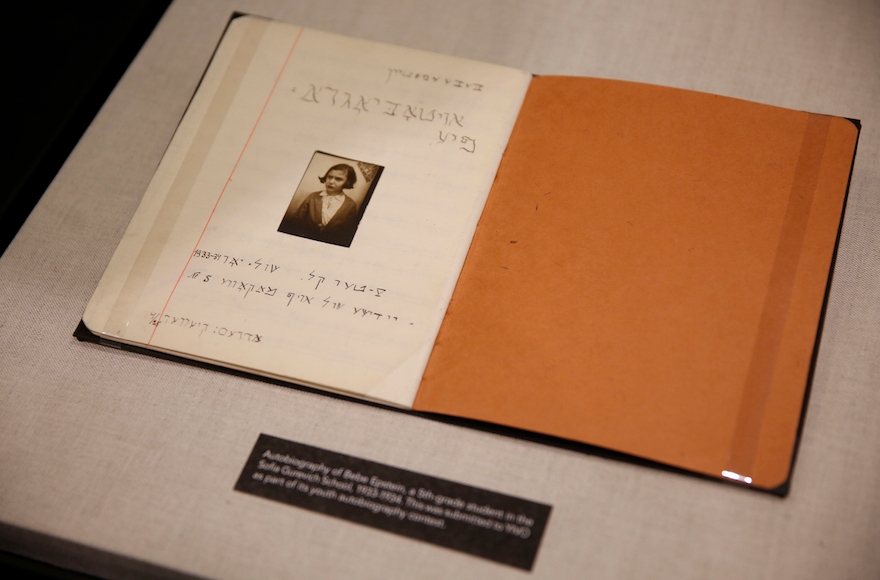

5. Autobiography of Bebe Epstein, Vilna, 1933-34

Vilna resident Bebe Epstein was 12 when she wrote this autobiography. (Thos Robinson/Getty Images for YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

Epstein was 12 when she wrote this book and submitted it to YIVO for a youth autobiography contest. The fifth-grader writes about the day-to-day happenings of her childhood, such as dealing with a strict teacher: “At first, he was good to us. Later he got strict, and even stricter.” Epstein also detailed various illnesses she suffered from and complained about having too much homework. Epstein was later forced to live in the Vilna Ghetto and in concentration camps, but she survived the war and moved to the United States.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.