NEW YORK (JTA) — The Jewish Sunday school teacher, a black accordion strapped to her shoulders, stands before a photo of a 1927 Jewish protest in Warsaw and introduces her students to an important holiday observed by their ancestors.

It isn’t Passover, which has just ended, but another that is approaching in a couple weeks: May Day, the unofficial May 1 holiday celebrating workers’ rights.

“Socialism is the idea that everyone should have what they need,” says the teacher, Hannah Temple, as a projector flashes images of a protest sign and Jewish immigrants marching in a labor demonstration. On the walls, multicolored signs declare “Jewish communities fight for $15” — a minimum wage campaign — “We are all workers” and “Remember the Triangle Fire,” a reference to the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire that killed 146 garment workers at a factory and galvanized the labor movement.

Temple teaches the children words to a Yiddish May Day anthem and offers a short primer on early 20th century labor activism.

“We need to sleep some, we need to work some, but we need some time that’s for us,” she says, describing the campaign for an eight-hour workday. She invites the few dozen students and parents in the room to a May Day protest in downtown Manhattan. A few hands go up.

“Maybe?” she asks. “Maybe is great.”

The Yiddish sing-along-cum-socialist teach-in is the morning meeting of the Midtown Workmen’s Circle School, a secular Jewish Sunday school that combines Yiddish language and culture education with progressive social justice organizing. It’s one of eight such schools, called “shules,” in four states serving a total of 300 students aged 5 to 13 — teaching them everything from an Eastern European melody for the Four Questions to how to protest on behalf of underpaid fast-food workers. The curriculum ends with a joint bar/bat mitzvah ceremony for the seventh-graders.

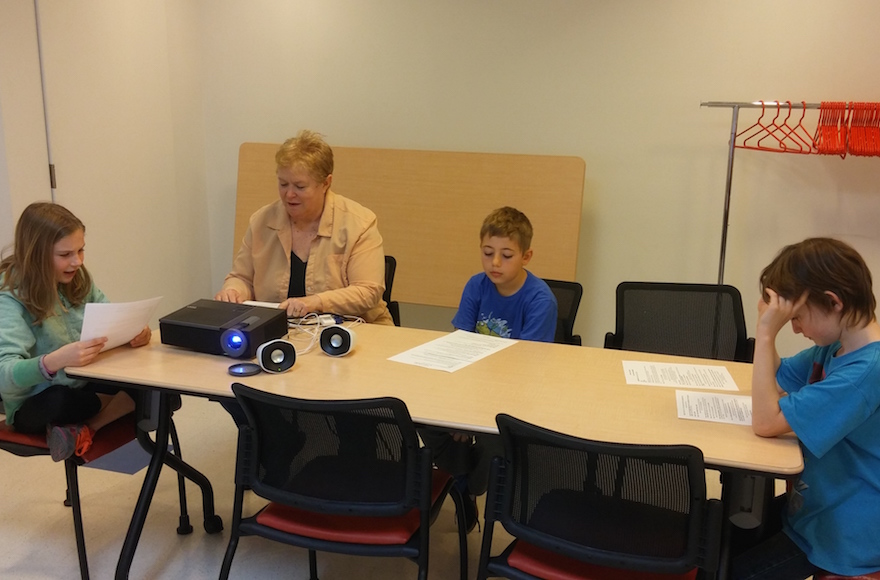

Students at the Midtown Workmen’s Circle School in Manhattan read through a play in Yiddish, April 23, 2017. (Ben Sales)

Though it’s more than a century old, the Workmen’s Circle, a left-wing Eastern European Jewish culture and social justice group, has seen its fundraising and school enrollment grow in recent years. Part of the boost, leaders say, was due to the diametrically opposed presidential campaigns of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Donald Trump.

Sanders, says executive director Ann Toback, awakened American Jews to secular, progressive Jewish culture conveyed with a heavy Brooklyn accent. Trump, she adds, sparked Jews on the left to organize in protest.

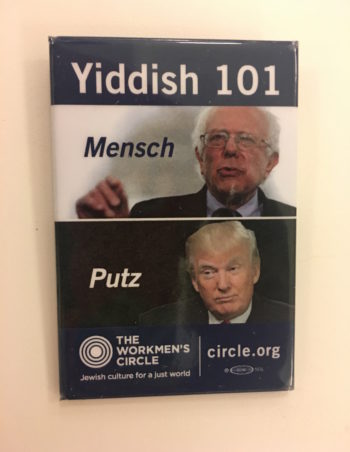

Workmen’s Circle made a lapel pin bearing the faces of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump accompanied by the words “mensch” and “putz,” respectively. (Josefin Dolsten)

Workmen’s Circle isn’t shy about its political leanings. Following the presidential election, it made a lapel pin bearing the faces of Sanders and Trump accompanied by the words “mensch” and “putz,” respectively.

“Before there was Bernie, there was the Workmen’s Circle,” Toback says. “Is there a way we can connect to so many of his followers? The values that he based his campaign on are really the inherent values of the Workmen’s Circle and our movement.”

In the five-month period after the election, the group saw its donations double over the same stretch the previous year. It has opened five of its eight Sunday schools in the past three years. The biggest, in Boston, has more than 100 students. In May, the Manhattan school will be hosting a spring open house for the first time.

“More people are coming to us looking for — ‘I want to engage in social justice activism,’” says Beth Zasloff, director of the Midtown school. “I know that for me, after the election, having a community, having a place to go where I know we can address these issues with our children, felt extremely important.”

The Midtown school, like its counterparts, eschews traditional Jewish Sunday school mainstays like learning Hebrew or studying ritual and prayer. Israel isn’t a focus. Workmen’s Circle has partnered in the past both with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, a left-wing group that focuses on domestic issues, and Habonim Dror, the left-wing Labor Zionist movement.

Instead, kids take three types of classes: arts and crafts, Yiddish language and history, and culture and social justice. Last Sunday, the three students in the Yiddish class were reading a play, in transliteration, about a robot. The teacher would read a line in Yiddish and translate, which a student repeated.

The arts and crafts class was making banners for an immigrant rights protest. In the history and culture class, four students prepared for their bar and bat mitzvahs next year. For the ceremony, they’ll do a research project on their family history and interview an elderly relative. Later that Sunday, this year’s bar mitzvah class made presentations on children who were killed in the Holocaust.

Beth Zasloff, director of the Midtown Workmen’s Circle School (Courtesy of Zasloff)

One student said knowing Yiddish made her feel like her friends at school who hail each other in the hallways in Bengali. Another said her favorite Workmen’s Circle experience was participating in the Jan. 21 Women’s March in New York City. And for some, the appeal lies in attending a Sunday school that avoids the standard memorization of Hebrew prayers.

“This is secular, and I’m not super religious in terms of my beliefs about God,” says Moxie Strom. “So it’s nice to have something that doesn’t focus so much on ‘God said this and God said that.’”

The Workmen’s Circle/Arbeter Ring was founded in 1900 in large part to help Jewish immigrants from Europe succeed in America. Along with advocating for better working conditions, it offered members services like health care and loans. It supported socialism at a time when Jews on the Lower East Side of Manhattan helped elected a Socialist Party candidate, Meyer London, to Congress.

No longer socialist but still left wing, the Workmen’s Circle fights for those issues largely on behalf of non-Jewish workers, leading campaigns for immigrant rights or better pay.

And instead of helping Yiddish speakers integrate into America, the organization’s cultural mission has flipped, preserving and promoting an old world culture for American Jews. It runs Yiddish language classes for adults and a summer camp for kids, and hosts culinary and holiday events.

“There’s so much culture they’re missing,” says Kolya Borodulin, the group’s associate director for Yiddish programming, who grew up in Birobidzhan, the Soviet Union’s Jewish Autonomous Region. “Jewish holidays, traditions described by famous Yiddish authors — any contemporary issues you name — are reflected in the Yiddish language. So you can see this parallel universe in Yiddish.”

Even if they go to eight years of Sunday school, Borodulin says, the students are unlikely to come out speaking proficient Yiddish, or even reading a page in the language’s Hebrew script. The school’s aim, rather, is to reinforce a cultural and ideological Jewish identity in its students. The aspiration is that years after they leave, they will be able to connect to their Judaism on holidays, in song and on the picket line.

“What resonates most with them is the social justice and having a sense of what we believe in,” says Debbie Feiner, whose two sons, ages 9 and 12, attend the Midtown school. The older one, she says, understands that “when you see some injustice, you need to take action. He can’t be a passive bystander, and he’ll connect that with his Judaism.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.