In celebration of its 2017 centennial, JTA is highlighting stories from its archive.

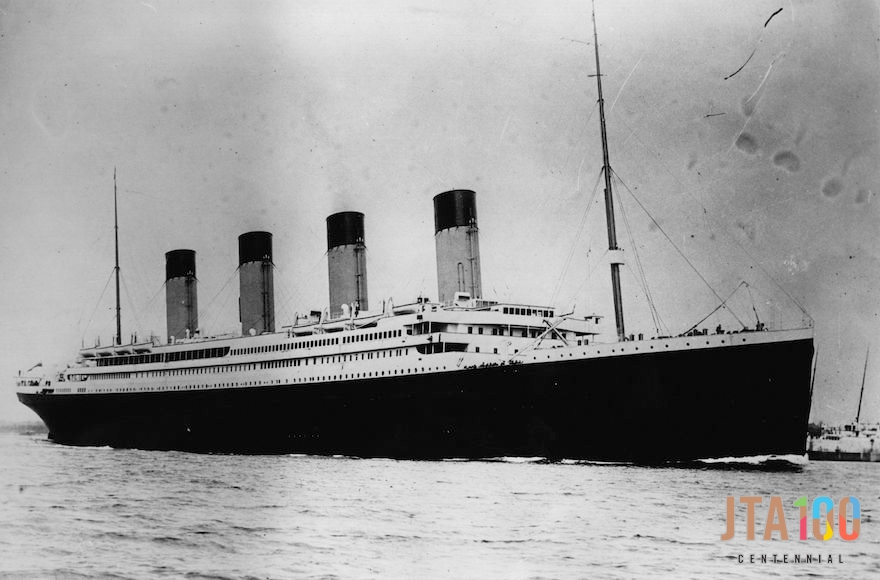

(JTA) — No one knows the exact number of Jews who were sailing on the Titanic, which struck an iceberg on its maiden voyage from Europe to New York on this date in 1912. One history of the ship’s sinking suggests hundreds of Jews were among the 1,517 victims of the disaster, from passengers in first class like the American businessman Benjamin Guggenheim, to poor Jewish immigrants who were traveling in third class. Kosher meals were served on board.

But one of the saddest codas to the tragedy belongs to a Jewish physician who survived the wreck, along with his wife and brother. Fifteen years later, on March 14, 1927, JTA reported on the death of Dr. Henry Frauenthal, a founder of New York’s Hospital for Joint Diseases.

According to JTA, the prominent physician “fell to his death from a bedroom window of his seventh floor apartment at 18 West Seventieth Street, early Friday. He would have been sixty-four years old on Sunday.”

Although the discretion of the era prevented the unnamed reporter from using the term “suicide,” the circumstances were made clear in later paragraphs:

Dr. Frauenthal’s partly dressed body was found in a back court at 7 a.m., after Miss Evelyn Robson, his secretary and nurse, had discovered his absence from the bedroom. The police and an ambulance from Knickerbocker Hospital were called. Medical Examiner Norris declared death resulted from “a fall from a window due to mental derangement.”

The surgeon had been suffering from one of his periodical nervous breakdowns for the last six weeks, according to Miss Robson, who said that he was confined to his bed for sixteen weeks last year and for a shorter period the year previous. He also was suffering from diabetes, a disease which several years ago forced the amputation, under his own supervision, of a number of toes on both feet.

The story notes that just a few days earlier, Frauenthal attended the funeral of one of his closest friends — Samuel Levy, a director of the Hospital for Joint Diseases – and “returned from the service in a state of deep mental depression.”

Frauenthal was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, studied and played football at Lehigh University and became one of the foremost orthopedic surgeons of his day. According to a history of the hospital – now part of the NYU Langone Medical Center – Frauenthal and his brother and fellow physician Herman were granted a charter in 1905 by the New York State Board of Charities for the “Jewish Hospital for Deformities and Joint Diseases.” The hospital opened the next year at 917 Madison Ave. in Harlem. It soon gained a reputation for successfully treating children afflicted by polio and other diseases.

Dr. Henry W. Frauenthal (U.S. National Library of Medicine/Public domain)

On March 26, 1912, Frauenthal and Clara Heimsheimer were married in Nice. They spent their honeymoon in France, boarding the Titanic in Cherbourg for their return trip. According to Frauenthal’s own account of the sinking, they were awakened around midnight in their first class cabin by Frauenthal’s brother, Isaac, who also was on board. Once on deck, Frauenthal ran into businessman Harry Elkins Widener (namesake of Harvard University’s library), who dismissed the talk of danger as “ridiculous.” Widener’s attitude “probably describes the mental state of nearly everyone on the boat, thinking that it was impossible for anything serious to happen to this paragon of modern ship architecture,” wrote Frauenthal.

Frauenthal and his new bride were among the 32 passengers aboard lifeboat No. 5, according to the website Encyclopedia Titanica. The same source said the physician, who reportedly weighed 250 pounds, “landed on top of Annie May Stengel and broke several of her ribs.” They were rescued by the RMS Carpathia at 6 a.m., more than six hours after the Titanic struck the iceberg. Isaac Frauenthal also survived; Widener did not.

Like many of the men who survived the disaster, especially among the rich, Frauenthal would have been dogged by accusations of cowardice and possibly feelings of guilt. He would recall, “When the vessel went down and for some time after, the cries of those who were on life preservers and floats were indescribable, and no one who heard these cries will ever forget them.”

And yet, in a 2012 interview with the Greenwich (Connecticut) Time, Stephen Frauenthal, the 72-year-old grandson of Henry’s brother Herman, doubts that his great-uncle’s suicide was the result of survivor’s guilt.

“He was diabetic, and the family understanding is he was fearful of more significant amputation than he had already encountered,” said Stephen.

Clara, too, was emotionally fragile, and after her husband’s death was treated for depression at a sanitarium in Greenwich. She’d live at the institution for another 16 years, until her death in 1943 at 73.

Henry Frauenthal’s story didn’t end with his death. On JTA reported that the Hospital for Joint Diseases was to receive “between $300,000 and $400,000” from his estate. His will included an unusual request, quoted in the article:

“I direct and it is my wish that my remains be cremated and that my ashes be deposited in the Hospital for Joint Diseases until October 4, 1955, this being the fiftieth anniversary of the incorporation of said hospital, and that they then be scattered from the roof of said hospital to the four winds.”

Nearly 30 years later, the hospital honored his wishes. The New York Times reported on Oct. 5, 1955, that his ashes were indeed “scattered yesterday from the roof of the hospital.”

According to the Times, the ashes, “in a heavy, green onyx urn with gold ornamentation,” were brought from the hospital chapel to the roof of the eight-story building by Abraham Rosenthal, the hospital’s executive director.

Herman Frauenthal “tossed the ashes by hand over a parapet facing north.”

RELATED:

How the Queen of England got involved in a secret Jewish wedding

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.