The conversation around legislating or limiting the practice of metzitzah b’peh, the oral suction by the mohel on a circumcision wound, has largely framed the issue as one of religious freedom, as secular government trying to unreasonably, and perhaps even unconstitutionally, proscribe protected religious ritual: the Department of Health vs. charedi and other Orthodox groups; the government against Judaism.

This is inaccurate in the extreme and clouds the nature of the debate, since it misrepresents the status of metzitzah b’peh within halacha, and thus within Judaism. Those who would practice metzitzah b’peh and decry government attempts to stop or control their practice of this aspect of bris milah liken their fight to the defense of shechitah (ritual slaughter), which has come under attack in parts of Europe. They act as if they are defending the entirety of a fundamental Jewish ritual against what can only be anti-Semitic or, at the very least, anti-religious, secular authorities. Such a frame is disingenuous.

There is no question that there are observant, halachic Jews who oppose the practice of metzitzah b’peh. I am one of them. But my personal opinion is irrelevant — halachic literature itself, the very text and legal culture from which the defenders of metzitzah b’peh take their authority, is quite clear that an infant’s health is the priority in performing this ritual.

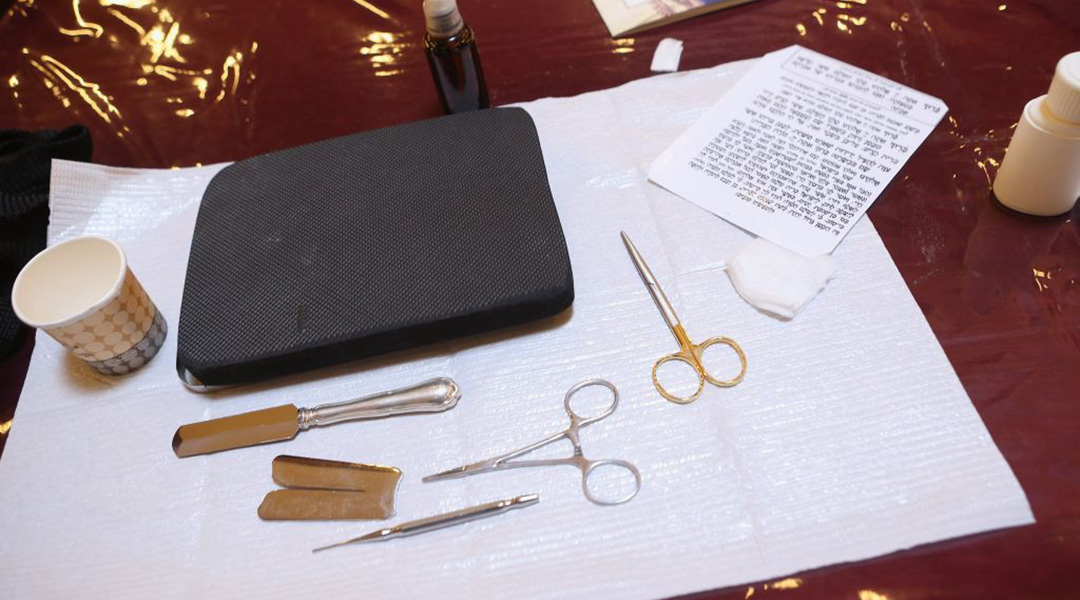

Metzitzah b’peh was originally mentioned in halachic texts (the Mishna, approximately 200 CE) as an entirely practical part of the procedure, along with placing cumin (thought to have healing properties at the time) and a bandage on the wound [Mishna Shabbos 19:2]. In the Gemara (written around 400 CE as a further discussion and clarification of the Mishna), Rav Papa states that “any mohel who does not suction creates a danger to life, and we remove him from his post” [Shabbos 133b].

Medical wisdom at the time held that bleeding a wound would help to clean it and prevent infection, as the streaming blood removed impurities. The rabbinic authorities of the time were actually acknowledging (and bowing to) the medical authorities, and acknowledging that keeping the child healthy was of utmost importance as part of the procedure, the mitzvah of performing a bris milah. So much so that a mohel who endangered the life of the child was “remove(d) from his post,” rendered unfit to perform a bris at all!

In the centuries of halachic opinion and culture that followed, all authorities (save one, the Ran in the 14th century) recognized metzitzah b’peh as a health measure and not in itself a component of the mitzvah.

A rav of no less stature than the Chasam Sofer, who is famous for his opposition to modern influences in halachic practice, even coining a famous play on words that “anything new is forbidden according to the Torah,” makes it clear that not only is metzitzah b’peh not a part of the mitzvah of bris, [Kochvai Yitzchak, 49-50] but it is clearly a health measure and we should certainly not engage in it if there is a risk to the child’s health.

He makes clear, broad and powerful statements, such as “we do not concern ourselves with the mystical when there is even a slight risk to the physical health of the child” [Kochvai Yitzchak, 49], referencing the connection between metzitzah b’peh and certain Kabbalistic ideas. He also makes quite clear that we should follow the “qualified physician” when told the best way to clean the wound, acknowledging that metzitzah b’peh was originally (if, now, mistakenly) intended as a hygienic, not halachic, act.

There is no question among the vast majority of poskim (halachic decisors), rabbis and medical professionals that metzitzah b’peh poses a fatal risk to infants while conveying no health benefits whatsoever. It is time for this practice to stop being treated as a venerable or immutable part of halachic Judaism and instead viewed as the once current, now outdated and quite dangerous, practice that it is. Irresponsibly risking the life of an infant is not the behavior of a God-fearing, Torah-observant Jew. Frum Jews must line up on the side of banning this life-threatening practice in a public, visible way.

Perhaps just as importantly, politicians should know and understand the truth about the place of metzitzah b’peh within Jewish law. While they may be moved by the voting blocks represented by certain Jewish communal groups, they should not be moved by the arguments such groups make that metzitzah b’peh should be protected religious practice. Our elected leaders, especially Mayor Bill De Blasio, who made the control of metzitzah b’peh a campaign-worthy issue, have a responsibility to protect the most vulnerable of their constituents. Metzitzah b’peh must be curtailed and it must be a priority of local government to see that it is.

These two “musts” go hand-in hand. Recognizing the reality of politics, it may be difficult to convince even the most idealistic politician to follow his conscience if that means opposing a powerful, unified voting block. Currently, there is no significant group making a united, vocal argument against metzitzah b’peh. In such a vacuum, it is easy to understand why this issue has remained mired in the grey for so long. I call on Jewish leaders and laymen who consider themselves halachic people of conscience to make their voices heard in opposition to metzitzah b’peh, so that the sanctity and morality of halacha can be upheld and our children can be kept safe. Visit safebris.org for more information and to add your name to the cause.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.