NEW YORK (JTA) — How do people behave when they visit a concentration camp or a Holocaust memorial?

Do they act as if there are in place of reverence or mourning? Or do they behave as crowds do at any tourist attraction — taking selfies, goofing around, snacking and drinking as they amble along?

Just what constitutes appropriate behavior at a Holocaust memorial site has been a hot topic recently. Last month, the Israeli-German writer and satirist Shahak Shapira reignited the public debate about “Holocaust tourism” with a website “shaming” tourists who appear in flippant selfies taken at the Holocaust memorial in Berlin. Shapira’s site, titled Yolocaust, superimposed smiling tourists with gruesome images from the Holocaust, such as piles of corpses.

“I find it dangerous that this is becoming normal,” Shapira told a German news program shortly before shutting down the project, saying it had served its purpose. “It kind of suggests that people are not dealing with the real purpose of this memorial.”

Last summer, the smartphone game Pokemon Go raised eyebrows for guiding some of its users into the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum as well as the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. This followed a few years after an American tourist took a smiling selfie at Auschwitz, drawing outrage on Twitter and calling attention to other online chronicles of inappropriate selfie-taking, such as the Facebook group “With My Besties in Auschwitz.”

And now the behavior of tourists at Holocaust memorial sites — and the tough questions surrounding it — is explored in a probing documentary film, “Austerlitz,” by Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa. The film will have its U.S. premiere at the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight festival on Sunday and Monday in New York City, but it has already garnered praise after showings last year at major international film festivals in Toronto and Venice.

Presented without commentary, the 90-minute black-and-white film is a series of long, lingering shots of tourists walking around Dachau and Sachsenhausen, a former concentration camp near Berlin. Loznitsa placed stationary cameras around the camps, capturing thousands of visitors sauntering in and out of the frame. It is unclear whether Loznitsa hid his cameras, although the tourists seem oblivious to them.

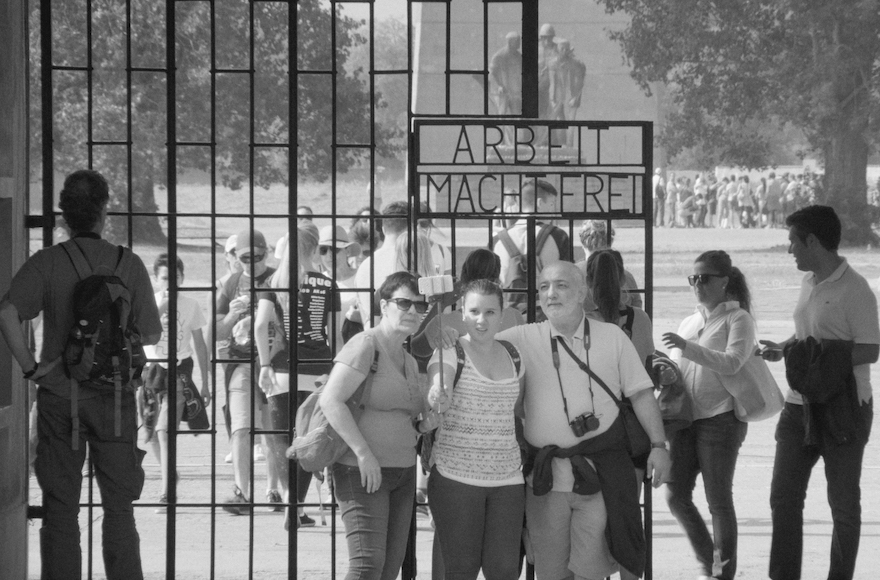

Most of the visitors seem as if they are walking in a shopping mall or perhaps an art museum. They mostly look aimless, restless, tired and bored. Some laugh and smile as they file into a room, like they are headed to a party. Some stand out due to their unfortunate sartorial choices — one wears a T-shirt with an image of a skull, another with the phrase “Cool story, bro.” Some take smiling selfies or lighthearted group photos in front of Sachsenhausen’s “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate.

The tourists in “Austerlitz” seem oblivious to Sergei Loznitsa’s cameras. (Courtesy of Austerlitz/Loznitsa)

Despite its lack of narrative or plot, the film is oddly compelling. The disconnect between setting and character provokes a range of feelings. The sight of crowds pouring into a room is creepily reminiscent of Holocaust prisoners being shepherded into train cars or gas chambers. Footage of visitors trying to get their tour headphones to work is amusing — until it isn’t. The fact that some visitors joke around or act like they’d rather be anywhere else inspires feelings of anger (at least for this viewer).

“The people who came to these places 40 years ago came with a different purpose than people now,” Loznitsa told The New York Times last year. “Now people don’t remember, and sometimes I think they don’t even understand where they are and what the places are about.”

The film takes its title from German writer W.G. Sebald’s final novel, “Austerlitz,” about an eponymous academic whose parents were killed in the Holocaust. The protagonist visits the Theresienstadt camp in the Czech Republic to learn more about his parents’ deaths, ruminating there on memory and history. Loznitsa has said his documentary is a “variation” on the novel. (The filmmaker was traveling this week and declined a request for an interview.)

The only dialogue comes in a few scenes involving tour guides — in the first, about 25 minutes in, a Spanish-speaking guide at Sachsenhausen begins to tell a group of tourists about the camp’s prison-within-a-prison system used to interrogate Jews.

Sergei Loznitsa set up stationary cameras in two concentration camps. (Courtesy of Austerlitz/Loznitsa)

But shortly after he starts his talk, a group of English-speaking tourists crowds the screen, obscuring the Spanish group. A British voice overlaps with the Spanish one. As the English group grows, one young woman balances a water bottle on her head. Eventually the Spanish group disappears almost entirely from view — shrouded by the nonchalant, English-speaking crowd — even though the viewer continues to hear parts of the guide’s talk.

The scene represents what could be seen as Loznitsa’s powerful thesis: It’s easy to be swallowed up by the tourist experience and forget to engage with the significance of a place — even at sites that commemorate one of history’s most horrid tragedies.

Still, none of the tourists captured by Loznitsa’s cameras are blatantly disrespectful. Nonchalant, yes, and somewhat self-absorbed in the 21st-century way. There are plenty of selfies in “Austerlitz” (including one particularly funny one involving an overweight man slowing rotating a selfie stick); even a man wearing a kippah happily poses for photos in front of the “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate.

By the end of “Austerlitz,” most viewers will likely feel conflicted about how to judge these unwitting tourists. After all, is it fair to judge someone by how they are captured on camera for a few minutes? And shouldn’t Jews be encouraged by the fact that Holocaust sites continue to draw record crowds? Doesn’t that signal increased interest in learning about Holocaust history?

Loznitsa’s point, however, is not about individual tourists — whether they choose to take a silly selfie or reflect deeply throughout their visit. The message, he has said, is that visiting a concentration camp should not be presented like any other mundane tourist experience.

“I think it must be like a church,” he told the Times. “If you want to pray for the souls of all the people who are in the ground in this place, then come.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.