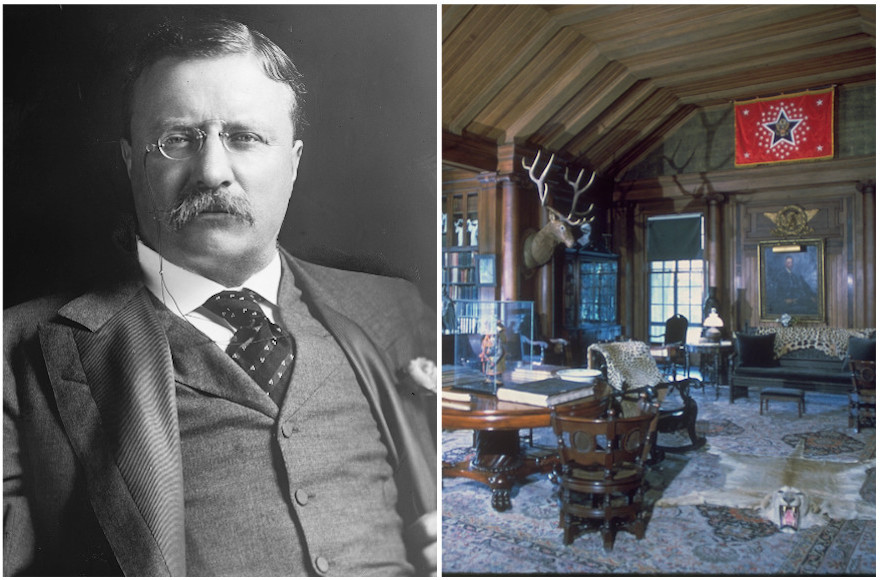

(JTA) — President Theodore Roosevelt’s summer home was decorated with the likes of African elephant tusks, a hippo-foot inkwell and other hunting souvenirs. That’s not terribly surprising, considering the 26th president of the United States published three books on hunting.

But the average armchair historian might be surprised to learn that Roosevelt, of non-Jewish Dutch ancestry, also kept two menorahs at Sagamore Hill, his 95-acre estate on the North Shore of Long Island, New York.

Roosevelt’s “Summer White House,” as it became known during his presidential years there, reopened to visitors last year after a three-year, $10 million restoration project. The Victorian home, which boasts 23 rooms, is still furnished as it was back in Roosevelt’s day.

As Alanna Sobel, a senior manager of communications at the National Park Foundation, described in a blog post earlier this month, one of the house’s most notable chambers is named the North Room. It measures 30 by 40 feet and was added to the house in 1905 to host guests and parties.

Among the artifacts in the North Room are books, mounted animal heads — and two golden menorahs.

According to Sobel, Roosevelt was given the menorahs by a Mrs. Leavitt — likely Sarah Bancroft Leavitt — whom he addresses fondly in multiple letters. Roosevelt presumably appreciated Leavitt’s gesture, since at one point he kept the menorahs on a bookshelf in the front of the room.

Oddly, while Sobel says that Leavitt came from a line of “theologians, abolitionists and Congregationalist ministers” who were “known to care deeply about religion and theology,” she was not Jewish.

Additionally, the menorahs she gifted to Roosevelt have seven branches — unlike the hanukiyah, the candelabra used on Hanukkah, which has nine (eight for the holiday’s number of days, plus the shamash to light the others). The seven-armed candelabras are still Jewish symbols and were used in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.

Nonetheless, Roosevelt had a close relationship with the Jewish community stemming from his time as a member of the board overseeing New York City’s police force near the turn of the 19th century. He recounted in his autobiography that he once assigned Jewish officers to oversee an anti-Semitic German preacher in order to mock him. By 1899, his support among Jewish New York Republicans was so strong that they printed fliers in Yiddish supporting his gubernatorial campaign.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.