(JTA) — Within the Jewish musical canon are several songs that seem to have always existed — tunes we all know and pass down from one generation to the next.

One example is the Hanukkah favorite “I Have a Little Dreidel” — chances are most everyone reading this can sing the chorus, at least. Another example, from a more elevated sphere of Jewish practice, is “Shalom Aleichem” — it isn’t hard to imagine Jewish families around the world simultaneously welcoming Shabbat with the familiar strains of this cherished liturgical melody.

What isn’t widely known, however, is that “I Have a Little Dreidel” and the melody most Ashkenazi Jews worldwide use for “Shalom Aleichem” were written in the early 20th century by two brothers from New York City.

Samuel E. Goldfarb penned “I Have a Little Dreidel” (with Samuel S. Grossman), while his older brother, Israel Goldfarb, composed “Shalom Aleichem.” To use a Christian equivalent, it would be like having one brother who wrote “Jingle Bells” and another who composed “Silent Night.”

A CD released last year, “Dreidel I Shall Play,” called renewed attention to the Goldfarbs and their achievements. The album features new recordings of Samuel and Israel Goldfarb’s holiday and liturgical songs from the 1910s and 1920s. The new song arrangements are by musician Craig Taubman, and the album attracted the participation of Neshama Carlebach and the late Theodore Bikel.

From left to right, Theodore Bikel, Craig Taubman and Myron Gordon in the recording studio in 2014. (Scott Christianson)

Driving the project was Myron Gordon, the now 96-year-old son of Samuel Goldfarb, who was aided by his own daughter, Tamar Gordon, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and his son-in-law Scott Christianson, an author. While the melodies created by the Goldfarbs have become staples of Jewish American life — insinuating themselves into happy memories of celebrations and gatherings of kin — Gordon said the tunes long held associations that represented the antithesis of family togetherness.

The Goldfarb brothers grew up on the Lower East Side of New York in a family of 11 children that emigrated from Galicia, Poland. Samuel was born in 1891, and learned how to read and play music from Israel, who was 12 years his senior.

In 1914, Samuel — who was making music in Yiddish theaters and other popular venues — entered into an arranged marriage with Bella Horowitz, from the family that owned Horowitz-Margareten, renowned makers of matzah and Passover products.

Gordon, their second child, was born in 1920, and still remembers visiting the matzah bakery when he was young.

“The factory took up a whole block of the Lower East Side,” he said. “I remember sliding down the flour slides in the bakery.”

While Samuel started out playing piano in theaters, Israel — a graduate of the Institute of Musical Art (now The Juilliard School), the Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia University — rose to fame as a noted cantor, and later became the long-serving rabbi at the venerable Kane Street Synagogue in Brooklyn.

He wrote his melody to “Shalom Aleichem,” a liturgical poem written by the kabbalists of Safed in the late 16th or early 17th century, in 1918. It’s popularity spread throughout the world, so much so that Israel said that “many came to believe this music was handed down from Mount Sinai by Moses.”

It wasn’t. Its popularity can be traced back to a compendium produced by the Goldfarbs in 1918 called “Friday Evening Melodies.” Over the next decade, the brothers — under the aegis of the progressive Bureau of Jewish Education of New York, where Samuel was eventually hired as the musical director —published expanded versions of this work known as “The Jewish Songster,” which was used by Ashkenazi congregations throughout the United States for decades.

The book remains a key document in the history of Jewish American music.

“Their mission was to present modernized versions of cantorial songs for Jewish Americans,” said Gordon, “as well as some of the Zionist songs coming out of Palestine and old Yiddish songs.”

During the 1920s, Samuel Goldfarb wrote “I Have a Little Dreidel.” (A highlight of the new album: a scratchy snippet of the original 1927 recording.)

“Generally speaking, in America Yiddish music influenced the popular music of Broadway and Hollywood,” he said. “With these kinds of songs, it was the opposite – it was an American tone being brought into a Jewish context.”

The dreidel song, adds Gordon, “took some time to catch on,” and did not do so until the early 1950s, “when Hanukkah was becoming more commercial and parallel to Christmas.” There was no single hit recording of the tune – its popularity as a folk song seems to have spread organically.

Gordon didn’t really know his father Samuel, who left his mother for a younger woman in 1929. With his new wife, Samuel moved to the West Coast, where he worked for years as musical director of a synagogue in Seattle. (Decades later, Gordon writes in the liner notes of “Dreidel I Shall Play,” his father “oversaw a performance space in the temple’s basement, where on one occasion he yanked from the stage an unconventional guitarist named Jimi Hendrix for his wild playing.”)

Samuel was unable to repair the broken tie with his son. Gordon writes in the liner notes: “I saw him again on just a few occasions — once, during the war, when I was in my Army uniform, visiting him in Seattle, he introduced me as ‘a friend.’” Gordon said his father met his own wife and children only once, in 1962. The family gathered around the piano and sang “I Have a Little Dreidel.”

By then, Gordon had dispensed with the Goldfarb name and had found his calling as a clinical psychologist. But he retained boxes of memorabilia from his father’s early career, including letters, songbooks, sheet music and recordings, which he rediscovered only a few years ago. Using that material to reconstruct the past and give the songs and stories behind them new life was a form of therapy, he said.

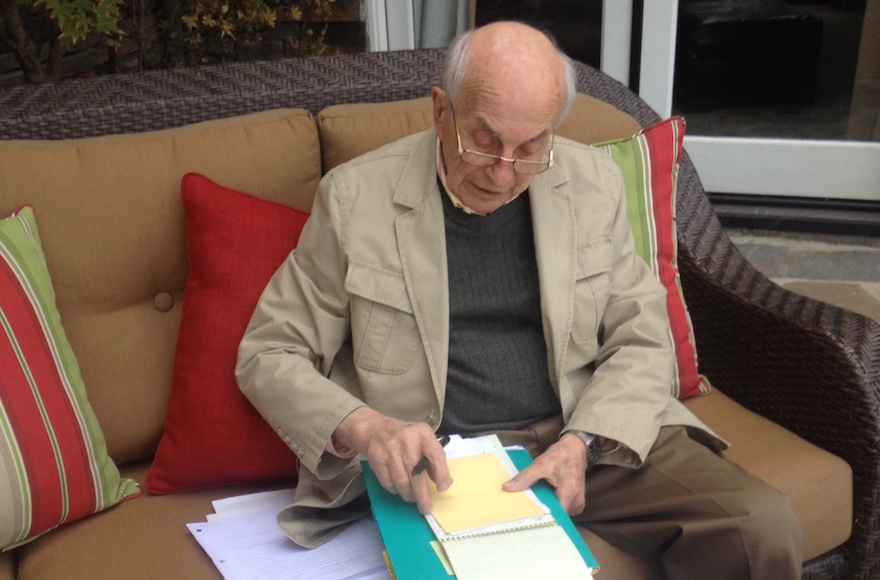

Myron Gordon (Scott Christianson)

The result is the album. The holiday and biblical songs on “Dreidel I Shall Play” have an old-fashioned charm, and Taubman’s arrangements are contemporary and lively. The standout song is “Little Candle Fires” performed by Bikel — in one of his last recordings — a sweet, sentimental holiday tune that deserves a place in the Hanukkah pantheon.

Musical virtues aside, the release is equally distinguished by Gordon’s retelling of his family story in the liner notes. Family history, generally speaking, had never brought him much happiness, but he says the completion of “Dreidel I Shall Play” has helped him salve the hurt of early wounds.

“Finally, I was not a passive victim of my father’s leaving us or the yearnings it caused,” Gordon said. “I went in the other direction, to produce something that would give me a better association with my father. For me, the songs no longer represent defeat. They represent at last what they were intended to.”

(A version of this article originally appeared in the Berkshire Jewish Voice, where Albert Stern is the editor. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Salon, Nerve, the Forward and WAMC Northeast Public Radio.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.