LAWRENCE, Kan. (JTA) – Joanna Slusky places a test tube into an incubating shaker, flips the switch, and it begins to quiver. So does she.

“I’m excited,” she said, showing off another gadget in her lab, a contraption that stirs solutions using a magnetic coil and a metal bar. “How great is that?”

It’s pretty great — so great that even a psychology major feels the excitement. The work that Slusky is doing at the University of Kansas, where she is an assistant professor of molecular biosciences and computational biology, may ultimately save millions of lives.

A protein she designed appears to be one of the most promising responses yet to the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It’s a scourge that infects 2 million Americans each year — more than 23,000 fatally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some world health officials project that by 2050, antibiotic resistance, if unchecked, could be responsible for more deaths globally than from all forms of cancer combined.

Slusky’s innovation earned the attention of the Palo Alto, Calif.-based Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which in November named her one of the first five Moore Inventor Fellows. As such, she will receive $825,000 over three years to fund her research, including $50,000 a year from the University of Kansas.

It’s an important crossroads for the prospects for global health and a remarkable achievement for the 37-year-old Jewish biochemist, who never saw herself as an “inventor scientist”— a term she admits that she, well, invented.

Growing up in an observant Jewish home in New Jersey, Slusky knew from a young age that she wanted to be a scientist. That’s largely thanks to her mother — a Bell Labs physicist who was one of the first women to earn a doctorate in physics at Princeton — who made science “sound like fun,” Slusky told JTA.

“There was a car ride that has become one of our family stories,” she said. “The conversation topic was, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ My mother was describing how, as a scientist, she shoots lasers at crystals. My father is a patent attorney, and he told us how he talks to people and he writes things. And I said, ‘OK, I’m going to be a scientist.’ And my brother said, ‘Can boys be scientists, too?’”

Slusky attended both Orthodox and Conservative day schools and has always kept Shabbat and kashrut. She said her identity is shaped by both her Jewish tradition and her work.

“It’s something I think about a lot,” she said. “I believe that science is fundamentally answering the question of ‘how,’ and Judaism is answering the question of ‘why,’ and those things aren’t in contrast for me. They’re very much two sides coming together.”

Slusky’s first job in the sciences, technically, was as a high school-aged babysitter for the children of a professor of molecular genetics. When he learned that she was interested in biochemistry, he connected her to Dr. Terry Goss Kinzy at Rutgers University, in whose lab she worked for two summers.

From there, after earning a degree in chemistry from Princeton, to further nurture her commitment to Jewish learning she spent a year at the Drisha Institute for Jewish Education on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. She then pursued a doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biophysics at the University of Pennsylvania, followed by postdoctoral work at Sweden’s Stockholm University and the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. She joined the University of Kansas faculty in 2014.

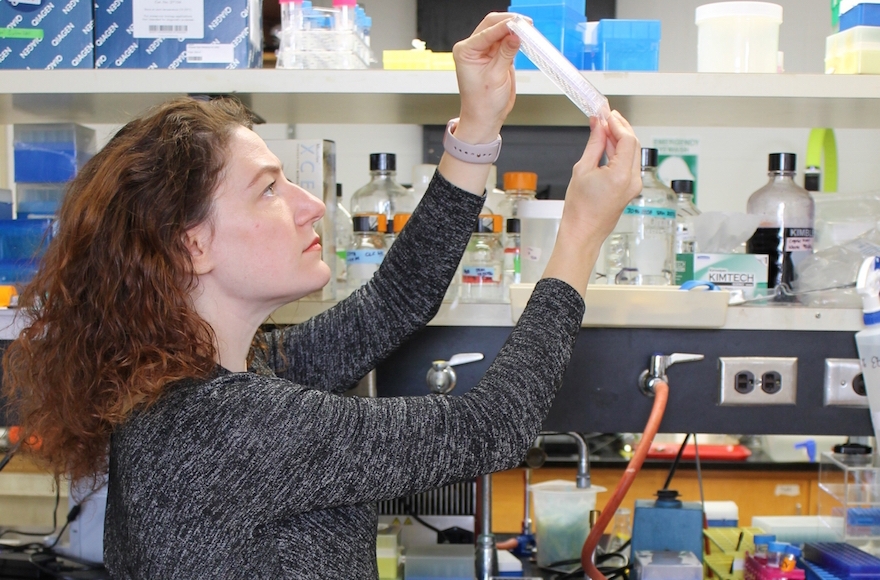

Joanna Slusky designed a protein that appears to be one of the most promising responses yet to the threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. (Ryan Feehan)

Along the way, Slusky discovered protein design, which is the study — and application — of the relationship between amino-acid sequencing and resultant 3-D protein structures. Shortly after establishing her lab at K.U., while investigating what she calls a “scientifically interesting” question about protein-protein interactions, she created a new protein, but eventually set it aside.

“And then, through conversations with colleagues about antibiotic resistance, I got to thinking, ‘I wonder if this protein that I have in the freezer could make bacteria susceptible to antibiotics,” she recalled. “The whole goal of my work is, instead of making new antibiotics, to make the old antibiotics work like new.”

Due to what some consider overprescribing and overuse in agriculture, antibiotics today are present in water and soil, where bacteria can develop resistance. While some resist due to mutation of the bacteria target-proteins or the modification of the antibiotic itself, the broader problem is when an antibiotic cannot reach its target due to something called an “efflux pump”— essentially a protein that pushes antibiotics right back out through the bacteria’s membrane. Slusky’s protein disables that pump.

She is not the first to attempt this, but previous efforts have focused on different proteins in the efflux pump, often with toxic results. What distinguishes this protein is that it targets the bacteria’s outer membrane — a feature absent from all human cells, which therefore are not vulnerable to unintentional attack. Slusky’s protein should therefore be nontoxic and more potent against the bacteria.

The call for applications from the Moore Foundation — established by Intel Corp. co-founder Gordon Moore — came shortly after Slusky’s breakthrough. The funds will allow Slusky to expand her lab, while the publicity could garner more interest and resources, helping her establish enough data to ready the protein for clinical trials — and possibly an approved, effective treatment within 20 years.

“It’s just fantastic,” she said of the accolades and the potential to help save lives. “Hopefully it will snowball.”

Regardless, Slusky knows there is much work ahead — though, of course, not on Shabbat, which she and her family observe. Slusky and her husband, David, an assistant professor of economics at K.U., and their young daughter are active members of their Conservative synagogue in the Kansas City suburbs.

Last Shavuot, Slusky taught a class on Torah and science. Among many topics, she addressed Abraham Joshua Heschel’s philosophy of “radical amazement” at the miraculous, natural world around us.

Slusky said it is science that gives her that sense of awe — whether it’s teaching informally among the students and researchers on her staff, helping a hall full of undergrads discover biochemistry for the first time, or working alone in the lab.

“The intricacies of protein-protein interactions and discovering new things about them is what fills me with radical amazement, which is a fundamentally religious feeling,” she said. “I also believe I have a responsibility to the world, that my obligation is to bear the burden of the other. And if I have the opportunity to do that on a global scale, then that’s really exciting.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.