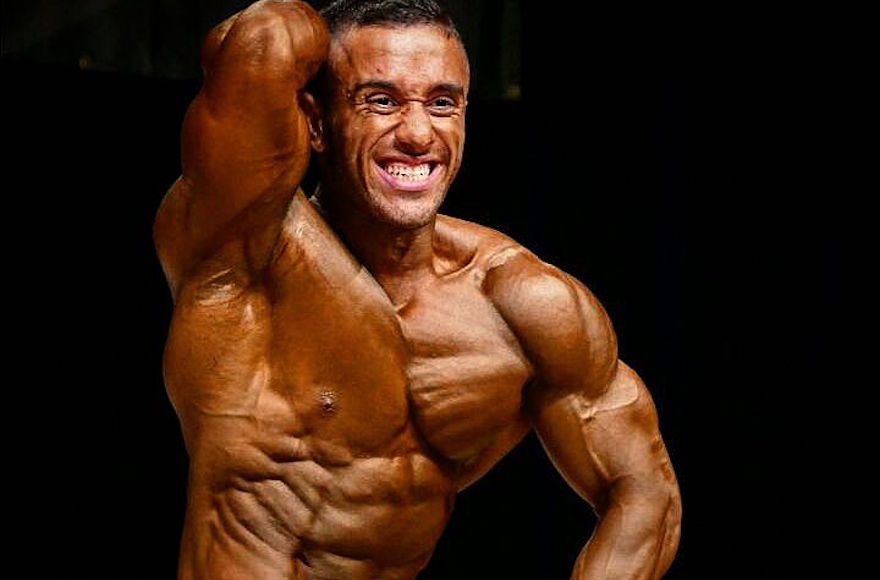

ZICHRON YAAKOV, Israel (JTA) – Kobi Ifrach stood on a stage in England wearing nothing but gold body paint, a Speedo and an Israeli flag. He had just become the first Israeli to win the Junior Mr. Universe bodybuilding competition.

Back home in this northern Israeli town, Ifrach’s haredi Orthodox parents were cheering him on. Days earlier they had lit Shabbat candles and prayed for his victory.

Ifrach, 20, left the path of strict Jewish observance during high school and now abides instead by the strictures of bodybuilding — working out for hours every day and following a carefully regimented diet. But he remains close with his family and credits much of his success to the discipline of his religious upbringing.

“Since you’re young, they teach you to have a strict order to your days. You have to wake up in the morning and pray and wrap tefillin, and you take this discipline with you wherever you are in life,” Ifrach told JTA. “I still have this order and this discipline of doing the things I need to do.”

Ifrach grew up in Zichron Yaakov, the youngest of eight brothers and sisters born to Moroccan immigrant parents. The children attended haredi Orthodox schools.

Two of Ifrach’s older brothers introduced him to weightlifting when he was 11 years old. At his yeshiva in Tiberias, he would hide dumbbells under his bed and skip prayers to work out. In class, he would doodle pictures of superheroes and bodybuilders instead of studying Torah.

“Bodybuilding chose me. I didn’t choose it,” Ifrach said. “I liked something about these very masculine characters. I was interested in them.”

After a brief stint in an all-boys army preparatory program, Ifrach dropped out of school and moved home to devote himself full time to bodybuilding.

Kobi Ifrach standing outside his under-construction apartment building in Zichron Yaakov, Nov. 25, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

“I couldn’t sit and study while I was thinking of working out. I needed to do what my heart wanted,” he said. “Anyway, I don’t think I would have continued with religion. It wasn’t in my soul.”

Ifrach’s parents tried to convince him to stay in the haredi world. His obsession with bodybuilding made little sense to them.

“I was worried. I didn’t know where it was going to lead,” his mother, Ruti, said as she prepared Shabbat dinner. “He was making a balagan [fiasco] in the kitchen every time he needed to eat. I was waking up in the middle of the night thinking the house was on fire. I’d come into the kitchen, and he’d just be eating his rice and chicken.”

“Our parents always wanted us to go their way, to stay in the haredi world, for the men to study in the yeshiva, for the women to be daughters of Jacob,” said Ifrach’s sister, Hagit, 37, using a term for an ideal haredi woman.

Kobi Ifrach, left, and his mother, Ruti Yifrach, holding the Mr. Israel trophy in Netanya, Israel, May 19, 2016. (Courtesy of Kobi Ifrach)

Ifrach eventually moved into an apartment in a nearby non-haredi neighborhood with his brother Mayer, a 26-year-old special needs teacher and amateur bodybuilder. They still live together, along with a gregarious Rottweiler named Revi. Together they own and manage a bodybuilding supplement shop called Kobi Body. Their apartment is filled with Ifrach’s trophies and medals, as well as one photo of the two beefcake brothers nearly nude.

Seven days a week, Ifrach wakes up and drinks a protein shake before spending 30 minutes practicing poses in front of the mirror. An hour later he eats a portion of tuna and rice. Two hours after that he lifts weights for three hours and drinks another protein shake, sometimes followed by running stairs.

Lunch is a portion of chicken breast and rice. After a few hours — typically spent working at the supplement shop — he has dinner: an omelet made from a dozen eggs, nine of them without the yolks.

At day’s end, he poses in the mirror for another 30 minutes before sending off a selfie to his trainer, Dani Kaganovich, another young bodybuilder who has won several international tournaments. Together they tweak the regimen for the following day, including how many grams he will weigh out for each meal.

Kobi Ifrach running on the beach with his dog, Revi, May 20, 2016. (Courtesy of Kobi Ifrach)

Ifrach’s regimented life leaves little room for hobbies and friends. Along with his brother, he spends most of his free time with his girlfriend, Yuval Azulay. Ifrach likes to cook for her, even if he can’t enjoy the results.

Azulay is 18 and doing national service for the Magen David ambulance service before starting a career in teaching. In an inverse situation to Ifrach’s, she comes from a secular family but became observant.

Ifrach competed in his first bodybuilding competition, the Mr. Israel junior event, in the coastal city of Netanya in 2012, at 16. He finished second, but the next year he took first place. He followed up in 2014 by winning the Mr. World youth competition in Malta, then took the title again the following year in Brazil.

As Ifrach rose in the bodybuilding world, his family came to support him, and with them came much of the community. By all accounts, the process started with his mother.

“You have to understand, my father is a very respected rabbi in the community. Everyone is seeking his advice and coming here to consult with him about religious and personal issues,” Hagit Ifrach said. “Seeing Kobi on the stage the first time, wearing only underwear, was a shock. But they saw my mother come up after he won with a wig and a long dress and a head covering, and hugging and blessing him. When that happened, everybody understood it was OK.”

Yuval Azulay, left, kissing her boyfriend, Kobi Ifrach, after he won Junior Mr. Universe in Birmingham, England, Oct. 30, 2016. (Courtesy of Kobi Ifrach)

A little more than a month after winning Junior Mr. Universe in October, Ifrach is halfway through his two-month recovery period. Next year, or in 2018, he plans to compete for the men’s Mr. Universe title won four consecutive times from 1967 to 1970 by movie star and former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“Other competitors get drunk on their success,” Ifrach said. “They’re not focused enough on their training, so they won’t win again the next year. I will.”

Ifrach hopes to follow Schwarzenegger’s path to becoming Mr. Olympia, which he considers the highest bodybuilding title. But for now he is enjoying the time off, which he said is essential to his physical and spiritual recovery. It’s also important to his mom.

“At least for a couple months a year, he eats my Moroccan fish,” she said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.