JEDWABNE, Poland (JTA) — As German army troops invaded eastern Poland, Ichak Lewin’s family fled their town of Wizna.

On July 10, 1941, the Lewins approached the nearby town of Jedwabne, where hundred of Jews lived and had the means to shelter other Jews. But the Lewins soon realized they had come to the wrong place.

“We were on the cart when we smelled a fire and another bad smell,” said Lewin, recalling the day 75 years ago that has changed how millions in Poland and beyond think of the Holocaust years in that country.

Lewin was 10 when Jedwabne residents massacred hundreds of their Jewish neighbors, including three of Lewin’s uncles and most of his classmates. The townspeople, led by their mayor, rounded up at least 340 Jews and burned them alive inside a barn.

“When the smell reached us, so did word from non-Jewish passers-by that the people of Jedwabne burned the Jews,” Lewin said.

Known to few people in post-communist Poland prior to the 2001 publication of a book about it, the Jedwabne massacre was one of about 20 anti-Semitic atrocities during or immediately after the Holocaust perpetrated by Poles. It prompted the country’s previous president, Bronislaw Komorowski, to “beg forgiveness” for the actions of “perpetrators among the nation of victims,” as he said in 2011.

But in a country where anti-Russian sentiment is fueling a nationalist revival, historians, politicians and activists are engaged in a campaign to discredit the inconvenient accounts from Jedwabne and those who exposed them.

Lewin, who survived the war because he was rescued by Polish villagers, recalled the massacre at Jedwabne on Sunday to some 150 visitors who attended a low-key ceremony commemorating its 75th anniversary.

None of the villagers participated in the memorial event, which the mayor could not attend due to a previous engagement.

Sobbing, Lewin addressed his remarks in Yiddish to a photograph of his classmates, including one of his cousins, who were burned alive.

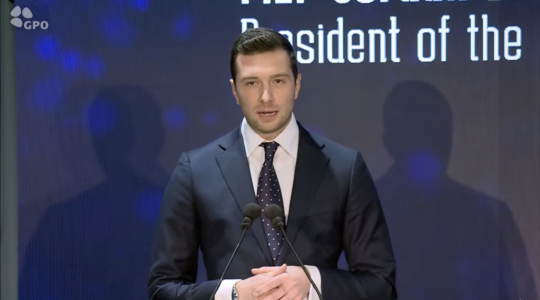

“I made a life for myself in Israel, but know that I think of you all the time,” he said at the ceremony, which was attended by Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt and Poland’s undersecretary of state, Wojciech Kolarski.

Kolarski, who chose not to speak at the event, told JTA that the Poles who killed Jews “damaged an ancient tradition” of coexistence in Poland. Poland’s right-wing president, Andrzej Duda, conveyed a similar message when he spoke earlier this month at the site of another pogrom, committed in 1946, against Jews in the town of Kielce.

But before Duda was elected president last year, he attacked his predecessor for apologizing in 2011 for Jedwabne and denied that such events actually occurred.

“We did not, as we are falsely accused by others, participate in the Holocaust,” Duda said in a 2015 televised debate. “Lord knows that Poles didn’t take part in the Holocaust.”

He has since changed his tune, at least publicly.

At Kielce, vowing to reject anti-Semitism, Duda said: “Also ordinary people were involved in the attack. I leave it down to historians and sociologists to determine how it happened and why it happened, why people reacted in this particular way.”

A senior state historian this week offered one answer to the questions raised by Duda: He blamed Jews of brutality against non-Jews before the 1941 German invasion, when the part of Poland that included Jedwabne was controlled by Russia.

“Poles took part in the crime” at Jedwabne, but pro-communist sympathies by Jews and “hateful acts perpetrated by Jews” stoked hate against Jews, Piotr Gontarczyk, a deputy director at the Institute of National Remembrance, said in an interview that Radio Poland published on the 75th anniversary.

The 2001 book “Neighbors” by the Princeton University historian Jan Gross, which exposed the Jedwabne massacre, has statistics and accounts that “don’t add up,” Gontarczyk said. Gross, he added, “is no historian.”

Gross, the Norman B. Tomlinson ’16 and ’48 professor of war and society and a history professor at Princeton, migrated to the United States from Poland in 1969.

Two “criminal ideologies are responsible for the events in Jedwabne,” Gontarczyk said in the interview: communism and Nazism. To determine what happened at Jedwabne, the bodies must be exhumed, he added – a scenario many Jews oppose on religious grounds.

Revisionist statements among officials such as Gontarczyk are a new development, according to Efraim Zuroff, the Israel director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

“Progress was made under previous governments toward confronting the Jedwabne massacre, which is emblematic of other pogroms by Poles against Jews,” Zuroff said. “The current right-wing government wants to turn back the page and rewrite it as it used to be.”

But he said historical documentation exists not only about Jedwabne – where witnesses said one Jewish girl was raped and decapitated by people who playfully kicked around her severed head – but also about 20 other cases of mass murder of Jews by Poles during or shortly after the Holocaust.

Jonathan Greenblatt, left, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, and Poland’s chief rabbi, Michael Schudrich, conferring at a ceremony commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Jedwabne massacre, July 10, 2016. (Courtesy of the ADL)

At least 1,500 and possibly 2,500 people died in the pogroms, Polish Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich said.

One of the incidents occurred a month after the Jedwabne killings in the nearby village of Bzury, where Polish prosecutors in 2013 said 20 Jewish women were raped and then butchered by locals. In another massacre in Wasosz, axe-wielding villagers hacked and buried hundreds of their Jewish neighbors.

For Poland’s Law and Justice party, Zuroff said, fully acknowledging these events “puts at stake their whole national identify because it changes the perception of Poland as a victim nation.”

Non-Jewish Poles certainly suffered in the war. The Nazis killed 3 million non-Jewish Poles in addition to 3 million Jewish ones and, as “lesser humans” under the Nazi racial code, Poles were not invited to collaborate in the same way as Hungarians, Romanians and the people of Baltic nations.

And like the people of other countries controlled by Russia during communism, Poles also suffered oppression and atrocities directed from Moscow – a trauma that has left widespread anger toward Russia and is helping the right wing garner votes in reaction to President Vladimir Putin’s current expansionist politics.

For Duda’s right-wing government especially, the discussion about Jedwabne clearly touched a nerve.

In recent months, Polish authorities began pursuing a criminal investigation of Gross, who exposed the massacre. Police questioned him in April for allegedly violating Poland’s law against “insulting the Polish nation” because he said in an interview recently that more Jews than Germans died at the hands of Poles during World War II.

In February, Duda’s office ordered an examination of the possibility of withdrawing a state honor given to Gross.

In parallel, the Polish government has led efforts to highlight the actions of 6,600 Poles who saved Jews, including by opening a museum in their honor this year and erecting three monuments for them in Warsaw alone. Poland has the highest number of saviors in absolute terms, though other countries have a higher proportion of non-Jews who saved Jews.

While Polish saviors deserve recognition, Gross said, in the current atmosphere there is a fear that “it’s an attempt to create an alternative narrative, to distract,” he told JTA.

If that is true, the effort is not going very well. Last year, the Jedwabne debate was rekindled following the publication of an English translation of a book written in 2004 in Polish by historian Anna Bikont that puts the Jedwabne death toll at double the 340 estimate of state historians. It also alleges that locals shot Jews trying to escape.

“I was saved by Poles to whom I owe my life,” Lewin said at the Jedwabne monument, a black stone whose center features a charred barn door. “But on July 10,” he said of that infamous day in 1941, “we were safer with the Germans.”

RELATED:

Jewish high schoolers picket Polish consulate in NY to protest ‘Holocaust whitewash’

Polish adman creates buzz with his pro-Jewish graffiti

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.