LOS ANGELES (JTA) — On Sunday evening, Jewish Oscar watchers viewers might keep an eye on two short films vying for the golden trophy in two of the lesser-watched categories.

“Ave Maria” (Hail Mary), from Palestinian filmmaker Basil Khalil, is among the five Oscar finalists in the live action short film category. “Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Holocaust,” a biographical documentary about the creator of the epic Holocaust film “Shoah,” is up for best documentary short.

In “Ave Maria,” Khalil makes the acute observation that Jewish-Israelis and Palestinians will cooperate only if that’s the only way they can get away from each other.

The film’s opening scene has an Orthodox Jewish family driving toward their West Bank settlement. The burly, bearded Moshe, his wife Rachel and sharp-tongued mother Esther are in a hurry because Shabbat will start in a few minutes.

Distracted, Moshe sideswipes a statue of the Virgin Mary in front of a small convent, knocking her off her pedestal. Inside the convent live five Palestinian Carmelite nuns of the Sisters of Mercy, who have taken vows of silence.

A noviate nun is sent outside to investigate the crash. She returns, gesticulating wildly and, in her agitation, breaks her vow of silence to exclaim, “The Jews have violated the Virgin.”

By now, Shabbat has arrived. And while the nuns have an ancient rotary phone to call for outside assistance, Moshe cannot break the Sabbath rules and use the phone. The nuns, of course, cannot speak. As they try to figure out how to get rid of their unwanted guests, antipathy becomes the mother of invention.

The solution involves an ancient car, the legacy of a deceased Mother Superior, which has been rusting away for years. With the aid of sacramental wine for the radiator and the incontinent Esther’s rubber diaper as a fan belt, the engine wheezes to life.

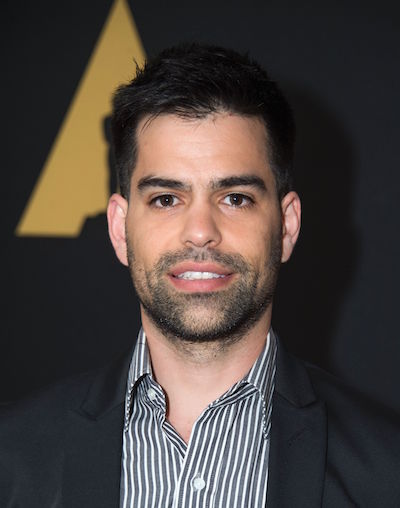

Basil Khalil, director of the Oscar-nominated short “Ave Maria,” in Los Angeles, Feb. 23, 2016. (Valerie Macon/AFP/Getty Images)

By this time, both sides have found ways to adapt inviolable rules to the present emergency and the nuns happily wave goodbye as Moshe and his family drive home into the sunset.

While the film is quirky and funny, Khalil, 34, born in Nazareth of a Palestinian father and a British mother, conveys the message in an email to JTA that “the voice of art is louder than that of the extremists and their bombs, which pitch us against each other.”

“Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Holocaust” is decidedly less lighthearted fare. In the film Lanzmann, whose 9 1/2-hour documentary “Shoah” attracted widespread acclaim, describes a moment halfway through the 12-year marathon required to complete it when he went for a dip in the Mediterranean Sea.

As the coastline of Israel receded, the director’s arms became quite tired and he realized he wouldn’t make it back. Just as he reconciled himself to drowning, a stronger swimmer came to his aid and helped Lanzmann back to shore.

“I wasn’t happy I was saved,” Lanzmann recalled, realizing he would have to go on with the Herculean task of finishing his 1985 film.

The near-death experience is one of the more dramatic recollections in the 40-minute film, in which Lanzmann discusses the seven years of filming and five years of editing required to produce “Shoah.”

“Making the film was total war against everything and everybody,” Lanzmann recalls in “Spectres.” “I was proud of what I had achieved, but it didn’t relieve me of my anguish.”

He added, “I was left with a sense of bereavement and it took me a long time to recover.”

Given that state of mind, Lanzmann had no desire to embark on a biographical documentary, especially since the most persistent requests came from a young journalist with no experience as a film director. That man was Adam Benzine, who was reporting mainly on films and music.

In 2010, Benzine saw “Shoah” for the first time and was blown away. As he began to look into Lanzmann’s background, he was amazed to discover that no one had tried to make a film about him. Over the next two years, Benzine repeatedly petitioned Lanzmann for an interview. Finally, in 2013, Lanzmann relented.

“Spectres of the Holocaust,” which Benzine wrote, produced and directed, is studded with dramatic moments, but one in particular stands out. In the segment — an outtake from “Shoah” — Lanzmann tells of hearing about a Jewish barber whose job in Treblinka had been to cut the hair of women going into the gas chambers.

Lanzmann tracked the man down and persuaded him to do an interview in a New York barbershop. While snipping a customer’s hair, the man, Abraham Bomba, first talks of his Treblinka assignment in a cold, neutral voice. Finally, Lanzmann asks Bomba, “What were your feelings while you were doing this work?”

Bomba bites his lips but refuses to answer, until Lanzmann finally tells him, “We have to do this.”

Benzine, who lives in Toronto, hopes his documentary will lead not only to an Academy Award but to a revival of “Shoah,” and that the two films will be shown in tandem.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.