TEL AVIV — The Mossad, Israel’s super-secret spy agency, is known for a lot of things: deep cover missions; swift, targeted strikes; a global web of intelligence that leaders the world over have learned to respect and fear.

What it isn’t known for is spilling secrets.

So when Israel’s Beit Hatfutsot-The Museum of the Jewish People announced that it was taking its landmark 2012 exhibition on the capture and trial of SS henchman Adolf Eichmann on a 2016 world tour, eyebrows were immediately raised: How in the world did the museum convince the Mossad to allow its precious artifacts of that mission to be taken abroad?

The answer lies with an 86-year-old Jewish businessman in Cleveland, who went from a career as a child actor in radio broadcasts to becoming one of the most influential Jewish philanthropists in America.

But first, let’s back up: “Operation Finale: The Story of the Capture of Eichmann” was revolutionary when it debuted four years ago at The Museum of the Jewish People. For the first time in Israel’s history, the exhibit offered visitors a firsthand look at many of the once-classified Mossad files that led to the capture of Eichmann, as well as the actual accouterments of the stakeout and trial that brought the Nazi war criminal to justice.

It was a huge coup when the museum convinced the Mossad to participate in the exhibition. The museum even convinced an active agent to be the curator — a covert operative who was listed on promotional materials simply as “Avner A.”

When “Operation Finale” opened in 2012, the glass booth in which Eichmann was tried was put on display, as well as the black-and-white photos that proved the man calling himself Ricardo Klement was actually one of the great orchestrators of the Nazi death machine. The exhibit also spotlighted the meticulous and often painstakingly slow detective work carried out by a team of Israeli secret agents who sought justice.

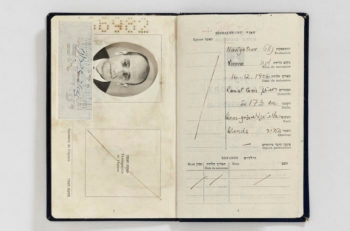

The falsified Israeli passport prepared for Adolf Eichmann in the name of Ze’ev Zichroni, including a photograph that was taken and developed in a safe house, 1960. (Mossad Archive)

Four years later, the Mossad has allowed another landmark concession: The exhibit has been updated and expanded, and will now make its international debut — secret files and all — in the United States on Feb. 17.

Perhaps not surprising, it took a lot of coaxing to convince the spy agency to open the exhibit to international audiences. The person who made it happen was Milton Maltz, a Cleveland businessman who sits on the board of Beit Hatfutsot. Maltz is the founder of the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage, where the new “Operation Finale” will open this month.

“It didn’t happen overnight,” Maltz said of the process. “We spent at least two years talking. But the Mossad became aware that they are part of an international world of intelligence, and as a consequence, the days of trying to hide the quality of their work were pretty much over.”

The evolution of the exhibit’s American iteration doesn’t have quite as many twists and turns as the stunning Buenos Aires stakeout that brought the Nazi henchman to a courtroom in Jerusalem, but it nonetheless reads a bit like a spy caper. There were secret meetings with undercover agents; long-distance telephone negotiations to discuss classified material; hours poring over forged documents and grainy surveillance photos.

Just how did Maltz persuade the Mossad to release the precious artifacts abroad? Like in most situations in life, it’s all about who you know.

Maltz, who began his career on the Chicago radio scene, worked his way up the broadcast industry’s ladder and later helped found both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. He also worked with the National Security Agency during his U.S. Navy stint in the Korean War and serves on the board of the CIA Officers Memorial Foundation.

With a foothold in the museum world, deep contacts in the international espionage community and a passion for Beit Hatfutsot’s mission, Maltz was uniquely placed to move negotiations along.

“Mr. Maltz is very persuasive,” said Ellen Rudolph, director of the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage. “And with his background in the NSA and his founding of the spy museum, he knows a little something about this world. It lends him immense credibility.”

She added: “Winning [the Mossad’s] trust to allow these artifacts to leave the country was a long and complex process, but we’re very excited it’s coming to fruition.”

The exhibit has been expanded dramatically for its tour. Spread out over 4,000 square feet, it’s more than double its previous incarnation in Tel Aviv. Its opening section has been bolstered to create context for an audience that did not grow up with the legacy of the Holocaust and what the ashes of 6 million European Jews have to do with the founding of the modern State of Israel.

“In Israel, they could just say ‘Eichmann’ — they didn’t even need to say ‘Adolf Eichmann’ because everyone knew who he was,” Rudolph said. “So we understood that in the United States, we needed to provide a bit more context. We also wanted to talk a bit more about the trial itself and the legacy of the capture of the trial.”

Milton and Tamar Maltz (Courtesy of the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage)

In addition to redesigning the exhibit to fit the expanded space, the staff at the Maltz Museum created seven films to accompany visitors throughout their journey, filling in potential gaps in knowledge.

There is also a zoomed-in focus on the gravity of the trial itself, which began in April 1961 and resulted in the second time in history Israel would ever use the death penalty.

“The case was really meant to put the Holocaust on trial, and to do it publicly,” Rudolph said.

After Cleveland, the exhibit will head to other major U.S. cities, said Beit Hatfutsot-The Museum of the Jewish People’s chief curator, Dr. Orit Shaham-Gover. Jewish museums in Chicago, New York and Atlanta have all expressed interest, and others are in the pipeline. This means the museum is navigating methods to transform the exhibit into one that travels and unpacks easily.

“It’s complicated but rewarding to do exhibitions in collaboration when you have 10,000 miles, one sea and one ocean between you,” Shaham-Gover said. “We’re learning a lot from each other about how we work.”

For Maltz, the reward has been well worth the effort.

“It’s pretty exciting stuff for a country like Israel, he said. “When we talked about it, we talked about how there is nothing new here that we are revealing — it’s a story that happened in 1961 and the secrets were already out. But as a museum, we are telling those stories with physical assets, with artifacts that have never before left Israel, and now they will.”

(This article is part of series sponsored by the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot, the sole institution anywhere in the world devoted to sharing the complete story of the Jewish people with millions of visitors from all walks of life. To learn more, click here.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.