NEW YORK (JTA) — There’s a memorable scene in “Annie Hall” when Woody Allen’s character, Alvy Singer, rants about finding anti-Semites everywhere he goes.

“You know, I was having lunch with some guys from NBC and I said, ‘Did you eat yet?’ and [they] said, ‘No, Jew?’ Not, ‘Did you,’ but ‘Jew eat? Jew?’ Not ‘Did you,’ but ‘Jew eat?’”

To which his pal Rob — played by the prolific stage and screen actor Tony Roberts — replies, “Max, you see conspiracies in everything.”

It’s an exchange that sums up a quintessential relationship in Allen’s oeuvre: the nervous, insecure schlemiel (played by Allen himself) and his level-headed, self-assured friend.

In several of Allen’s films in the 1970s and ’80s — including “Play It Again, Sam,” “Hannah and Her Sisters” and “Stardust Memories”— that role belonged to Roberts.

Roberts’ confident onscreen presence — not to mention his tall frame, broad shoulders and brown curly mane — was the perfect foil for Allen’s various neurotic characters, making them more funny and enjoyable to watch.

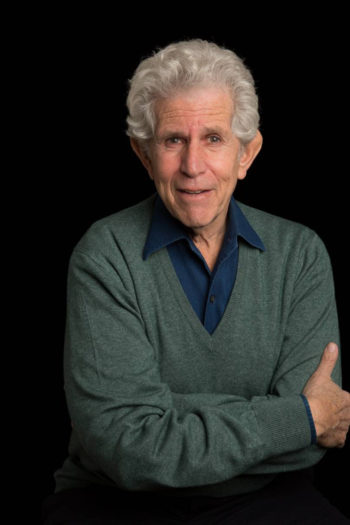

Still handsome at 76, though his curls have long since turned cloud white, Roberts says today that his comedic interplay with Allen was nothing less than serendipitous.

READ: Woody Allen to make TV series for Amazon

“I don’t even know what chemistry we lucked upon,” Roberts tells JTA. “[Woody] said to me, ‘You know, people like our schmoozing.’”

“Well, clearly people liked it because he made use of it in six films,” he adds.

Those films with Allen have been on Roberts’ mind quite a lot in the past year. The actor has published a new memoir that entertainingly dishes on his decades in film, theater and TV, and explores how he built a successful career while teetering somewhere between fame and anonymity.

In “Do You Know Me?,” Roberts writes that he could star in Broadway shows and hit films and receive critical praise — yet people would approach him on the street wondering where they had seen him before.

Aside from providing a peek inside his celebrity-filled life — the memoir is filled with anecdotes about working with legends like Sidney Lumet, who directed him in “Serpico” opposite Al Pacino, and Julie Andrews, with whom he co-starred in the Broadway production of “Victor/Victoria” — Roberts hopes the book will be a guide for young actors. He offers advice on preparing for auditions, inhabiting characters and observing human behavior as a conduit to understanding narrative.

And of course, there’s a lot about Woody Allen. Roberts calls Allen “Max” throughout the book, a nod to the personal nickname that started when the perennially introverted Allen told Roberts not to call out his name in public. In fact, the nickname “Max,” used in “Annie Hall,” is a direct reference to their off-screen joke.

Actor Tony Roberts in his new memoir dishes on his decades in film, theater and TV. (Kevin Thomas Garcia)

Robert’s fame never reached the height of a Robert Redford, whom Roberts replaced in the 1963 Broadway hit “Barefoot in the Park.” And in films, he typically plays the sidekick rather than the lead. But his nearly 60-year career reveals the strengths of a supporting actor who continually brought the main character’s desires and conflicts into greater relief.

As the legendary comedian Milton Berle once told him, “When I get a laugh, it’s our laugh.”

Today, Roberts looks back with a sense of pride, but he’s reluctant to call himself an artist. Sitting in Lexington Candy Shop, the classic Upper East Side diner he’s frequented since he was 7 years old, Roberts contemplates how to define his work.

“I’m like a musician in an orchestra,” he suggests. “An interpreter, not a creator.”

Roberts credits his Manhattan upbringing for providing a fascinating spectrum of characters to observe.

“It was like the whole world was here,” he says of city life. “There were ethnic collisions between newly arrived immigrants; there were Irish kids who went to school in ties but, after school, would see a weakling Jew and take it out on him.

“But on the other hand, I had Irish friends,” he adds. “I learned tolerance.”

His parents were secular Jews who raised their son to love culture and uphold a moral code of behavior. In his memoir, Roberts writes that though he was raised without religious observance, he grew curious about his heritage and took a trip to Latvia where his grandfather had lived before immigrating to the United States.

Roberts got an early start as a professional actor, landing a part on the soap opera “The Edge of Night” just after college in 1966. Soon after he was cast in his first Broadway play, and the roles multiplied from there.

READ: ‘Son of Saul’ nominated for best foreign language Oscar

He first met Allen backstage when he was starring in “Barefoot in the Park.” It was around the time that Roberts unsuccessfully auditioned — four times — for Allen’s first Broadway play, “Don’t Drink the Water.” Seeing Roberts perform in “Barefoot in the Park” convinced Allen that Roberts was talented and worth casting. According to his memoir, Allen told him, “You were great. How come you’re such a lousy auditioner?”

Roberts talks comfortably about all facets of Allen’s work — but on the topic of the director’s romantic and personal scandals, he eschews commentary. In fact, several publishers told him they would only publish the memoir if it included details about Allen’s personal life, Roberts says, so he decided to publish the book independently. There’s no dignity in divulging gossip, he says, and he maintains that the off-camera memories with Allen are more interesting anyway.

Today, Roberts and Allen are still good friends. And though they haven’t acted together in some time, Allen still screens his new films for him and seeks his feedback.

Thinking back on their most famous film together, “Annie Hall” — which won four Academy Awards in 1978, including best picture — Roberts says, “I don’t think Woody wants ‘Annie Hall’ to be his signature achievement. He would much prefer if it were one of his more obscure, experimental films. Like ‘Zelig’ — that’s the one they should put in the time capsule.”

As for Roberts, like all working actors, he’s excited about his next role, whatever it is.

“I wrote the book about the things I want to be my legacy — a love of acting and a love of performers,” he says. “The trick is to figure out what you love to do and then get paid to do it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.