WASHINGTON (JTA) — Hamilton Jordan, President Jimmy Carter’s wunderkind adviser and chief of staff, discovered at age 20 that his family’s story wasn’t a straightforward Christian Southern experience. At the cemetery service for his maternal grandmother, Helen, Jordan was puzzled to discover her plot was nestled alongside that of a Jewish family. They weren’t strangers; they were his ancestors.

A bit of digging revealed that his beloved grandmother was herself Jewish. She had married his Baptist grandfather in the years immediately preceding the 1915 lynching of Leo Frank — a Jewish man who was framed for a murder he did not commit — in a South that viewed Jews as unacceptably different. His own mother would never speak of her Jewish roots.

READ: Op-Ed: A century later, Leo Frank tragedy still resonates

Jordan died in 2008. That we know this story is thanks to his daughter Kathleen, now 27. A Comedy Central and Hollywood scriptwriter, Kathleen took on the task of editing the unfinished 300-page manuscript her father had left behind. It was a labor of love, a way to process her grief and an exercise in embracing her own Southern identity.

Kathleen Jordan sat down recently with Sarah Wildman at a Washington, D.C., coffee shop for a wide-ranging conversation about the family secret at the heart of the recently published memoir “A Boy from Georgia: Coming of Age in the Segregated South.”

JTA: The book seems to be very much about the evolution of American thinking about race and ethnicity.

Kathleen Jordan, who edited her father’s posthumous memoir, “A Boy From Georgia.” (Courtesy of Jordan)

Jordan: It’s largely tracking his moral journey in the context of race. I think a linchpin moment in the book and in his own life [was] realizing that he was the victim of persecution at age 20. Standing at that gravesite and realizing that his family was Jewish and that was a secret — and it was a secret for a reason.

Did he have an inkling? After he sees the gravesite, did he ask family members?

He asks his mother about this three times. First she says, ‘Later. It’s too much.’ [Eventually she says] ‘Hamilton, I’ll never talk of this.’

Before my dad died and when he was working on the book, it blew our minds that he wasn’t going to ask his uncle about it. It was 2006 or 2007, and we said, ‘Are you kidding? You have the chance to hear his stories and feelings of persecution he experienced — or even marginalization.’ It seemed a very quiet kind of thing. A social thing.

Did learning he was Jewish inform the way your father thought about the world?

Absolutely. He spent the rest of his life trying to connect with the Jewish community. He was baptized Baptist. We grew up Episcopalian. But culturally he was drawn to it. And it had an impact on his relationship to the civil rights movement; I think it made it personal for him. It made civil rights even more personal. There are two watershed moments for him: seeing his maid marching with [Martin Luther King Jr.] in downtown Albany [Georgia] and thinking ‘what am I doing?’ and realizing that everyone he loves and respects was a segregationist.

Why did you decide to pick up the book and edit it?

This book is about his childhood and the moral and intellectual journey to the right side of the fence, and because of that it took a long time for him to articulate. He had been writing and telling these stories for a long time. We knew how important it was to him. When he died it was 85 percent finished. We didn’t add. I drew some conclusions. I did polishing. Edited it. Made it into a narrative. He had had words on paper for maybe six or eight years.

Did you see this as a legacy project?

I think that this book started as an oral history, and he wanted his stories to live on and he was always aware that he could die of cancer. The book explains how he got to be a politician and how he came to formulate opinions. But when I took it on, it was partially a choice of grief. We were sad. My brother worked on it for six months and did research interviews. It’s a family affair.

The book is detailed about his childhood — and a bit less about his time serving in the White House. Did you have a consciousness about that era as a kid? Did you speak about, say, Camp David, the historic summit where President Carter managed to wrest a peace treaty out of the Israelis and the Egyptians?

Camp David was one of the most successful Middle East treaties to this day. It was something he was really proud of.

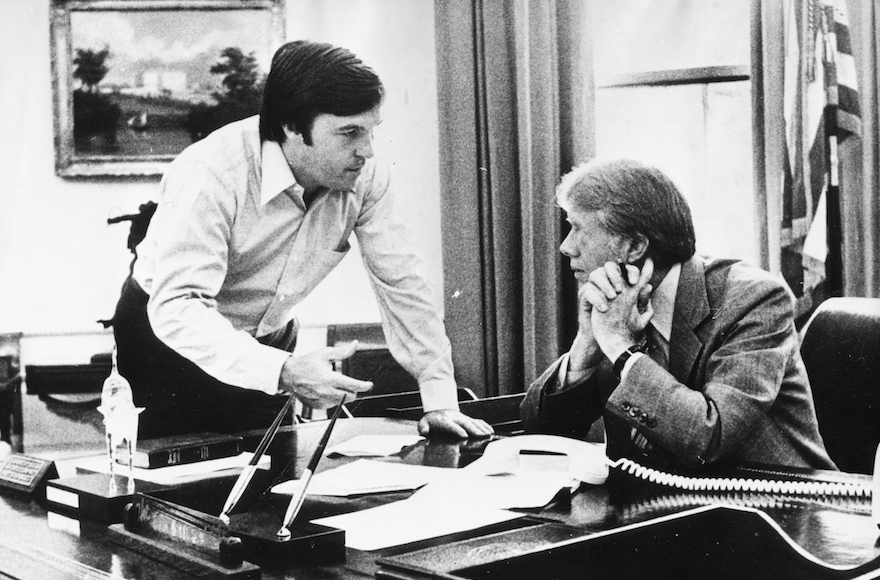

My dad’s story in a lot of ways is President Carter’s story — the slow opening of his eyes to human rights. It drew them together throughout their relationship. They had this common background of growing up where segregation is passed generation to generation, and it falls into your lap and you realize you have a choice … and that is a thread. And that empathy and human rights thread tied them together into a common mission.

Tell me about the cover art. It’s a Confederate flag and your dad as a boy. It’s a jarring image.

People often ask if it was a tough decision, especially after the [deadly shootings at a black church] in South Carolina. We discussed it. It is the perfect symbol for his journey. He is standing there blissfully unaware of the symbol, and he has no sense of its meaning. I think that slowly through the book he begins to understand that it is symbolically his choice to hold the flag.

READ: President Carter’s Al Het

How did working on the book change your own Southern identity?

I had a lot of shame associated with being from the South. But in working on this book, I have realized that not claiming your past is kind of a form of erasure. It is denying the bad and burying the good. And he didn’t run from it.

It was politically important for my dad, and being from the South was one of the main points of his identity. Now I would say it’s the same for me.

And I’ve been able to rediscover a lot in working on this book and being able to interact with some of his peers in Albany, Georgia, and Atlanta. Prejudice and race happen in the South — it is more so on the tips of our tongues. Living in New York and L.A., in my experience, I have not had as many interesting conversations on race because people aren’t as up to talk about it. But the South is anything but color blind, and it’s something I really value.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.