With the negotiated release of American Jewish government contractor Alan Gross this week and President Obama announcing his plan to lift the 54-year-old economic embargo against Cuba, the United States and Cuba appear to be opening a new — and warmer — chapter in their relationship. Which should be good news for the approximately 1,400 Jews, along with their 11 million non-Jewish countrymen, in this economically struggling Caribbean nation.

The U.S. embargo was imposed at the height of the Cold War and a year after Fidel Castro’s Communist 26th of July Movement dethroned Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

While the revolution, particularly Castro’s alliance with the Soviet Union, had a catastrophic effect on Cuba’s once friendly relationship with the U.S., its impact on the island’s Jewish population was less clear, at least at first.

On Jan. 4, 1959, JTA reported that over 100 Jewish stores were damaged during the riots that took place in Havana after Batista’s government collapsed. A report from a few days earlier described the tension:

Jewish stores in Havana were attacked today by mobs following the fall of the Batista government, while leaders of the Jewish community there were seeking reassurances from representatives of the new regime which brought Fidel Castro into power.

A number of Havana Jewish families, including children, arrived by air in Miami this morning. They reported that the atmosphere in Havana was tense when they left the city, and that the Jews there are afraid that hot-headed Castro partisans might rise violently in the streets against segments of the population whom they have in the past charged with backing the Batista regime…

But two days later, JTA reported that the previous story was probably “baseless” and that anti-Semitism was not involved in the unrest in Havana. In fact, several Jews held command positions among Castro’s forces and fought in the revolution. On Jan. 8, Israel formally recognized Castro’s government, and on Jan. 12, Enrique Oltuski, a Jew whose parents had emigrated from Poland and started a shoe factory, was appointed to Castro’s cabinet. Later in the year, Castro announced that his regime would not tolerate anti-Semitism.

For the next 13 years, even as Cuba and the U.S. were arch-enemies and the majority of Cuba’s Jews emigrated, Havana and Jerusalem enjoyed a cordial relationship. In 1966 that the Castro-controlled newspaper “El Mundo” lauded Israel’s innovations in the 18 years since its founding.

A year later, the Six-Day War soured relations, and the cordiality officially ended on Sept. 9 1973 when Castro suddenly broke all diplomatic ties with Israel. The move surprised many, including those in Castro’s own political circles. Since then, Israel has been one of the few countries to side with the U.S. in its blockade of Cuba.

Years later, after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, which had financially supported Cuba, the Caribbean island faced new shortages of food, clothing and electricity. JTA described the complicated situation:

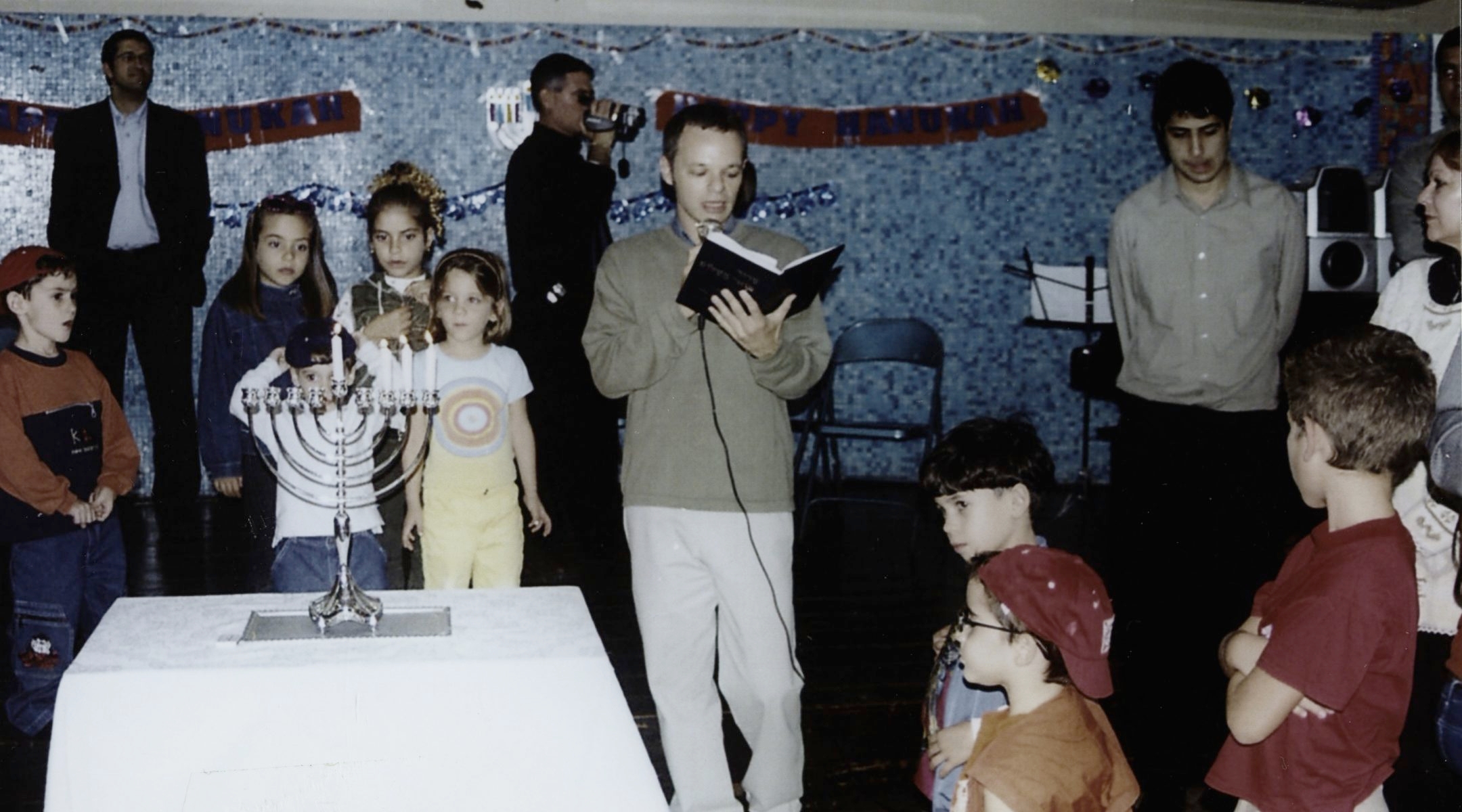

With fuel scarce, cars and buses are becoming increasingly rare sights. This has taken a toll on Jewish communal life; which revolves around four synagogues and a community center.

The [Havana Jewish] community numbers 305 families by [Jewish teacher Moises] Asis’ count, most of which include non-Jewish spouses. About 100 families buy kosher meat, but with oxen filling in for disabled tractors, “we’re going to become vegetarians,” said Asis.

This comes at a time when the last restrictions on Cuban Jewry are being lifted.

In October, the Communist Party lifted the ban on religious believers joining the party. This had discouraged some young Jews from affiliating with the community and blocked the professional rise of those that did so identify.

Since then, Cuba’s economic situation has become even more dire. Cuban Jews have relied in part on humanitarian aid from American Jewish groups like the Joint Distribution Committee.

If Obama is able to remove some of the embargo’s trade and travel restrictions, interaction between Cuba’s dwindling Jewish population and the strong Jewish communities of nearby Florida will most likely increase in years to come.

Whether or not Cuba’s Communist government will implement democratic reforms is yet to be seen.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.