The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) – Nancy Glickman was a teenager when she heard the story about her father at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin: Marty Glickman and another Jewish sprinter, Sam Stoller, were replaced as members of the 400-meter relay team for the U.S. squad on the morning of the event.

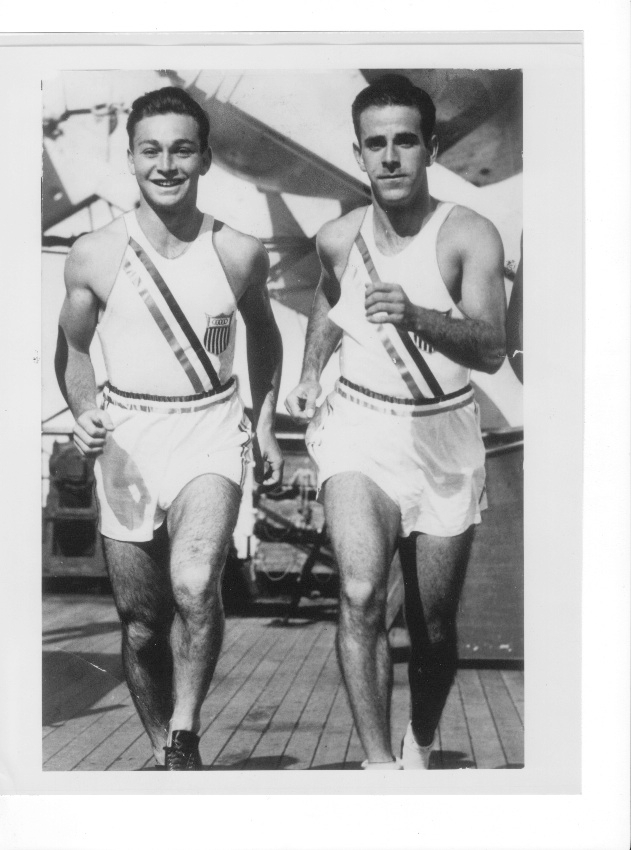

American sprinters Marty Glickman, left, and Sam Stoller, at sea traveling to the 1936 Olympics, were prevented from competing at the games in Berlin but will be posthumously honored at the 2015 European Maccabi Games there. (Courtesy Nancy Glickman)

Asking her father about the slight one night, he pulled out his uniform from the bottom drawer of a large dresser to display it. Right there, Nancy Glickman requested the item be bequeathed to her when he died.

Marty Glickman, “well before” his death at 83 in 2001, gave her the uniform, Nancy Glickman said, and she stores it in a duffel bag in her Washington, D.C., apartment.

“I’m the keeper of the uniform,” she said.

Maccabi USA, the Philadelphia-based branch of the Maccabi World Union sports federation, is hoping members of the Glickman and Stoller families will go to Berlin in July 2015 when the European Maccabi Games are held in the German capital and the memories of the two track stars are honored.

It will be the first time Berlin hosts the games, which started in 1929.

The organization did not know the whereabouts of the Glickman and Stoller families. Last week, “Seeking Kin” found them.

Maccabi USA Executive Director Jed Margolis said he will soon contact the relatives and hopes they will agree to serve as honorary captains, or bear the banner preceding the expected 150 American athletes and staff onto the field.

Nancy Glickman, at 60 the youngest of her father’s four children, said last week that Maccabi USA’s interest is “a very nice gesture.”

The organizers haven’t decided where the opening ceremony will be held, but one option is Olympiastadione, where the African-American sprinter Jesse Owens earned four gold medals 78 years ago — with Adolf Hitler in attendance — and where Owens’ Jewish teammates were to have competed, too.

Glickman believed the anti-Semitism and Nazi sympathies of several U.S. officials led to his and Stoller’s removal from the relay team.

“We feel sorry that Stoller and Glickman were denied the opportunity to run because of their religion,” Margolis said. “They had a great injustice done to them in 1936. It’d be wonderful to have someone from the family march in with us.”

Marty Glickman would go on to become a prominent sports broadcaster with recognition in several halls of fame. The native New Yorker’s resume included calling football games for his hometown Giants and Jets, as well as Knicks basketball.

The Newhouse School of Public Communications at his alma mater, Syracuse University, last year established the Marty Glickman Award for Leadership in Sports Media.

Its first recipient was Bob Costas, like Glickman an eminent sports broadcaster and Syracuse graduate. Costas, the host of NBC’s coverage of the Olympics, played a pivotal role in connecting “Seeking Kin” with Glickman’s family, requesting that Syracuse provide their contact information.

Costas recalled that Glickman, whom he admired greatly, would discuss the Berlin slight if asked.

“He lived in the present, but with a strong sense of the past,” Costas told Seeking Kin. “He didn’t nurse any grudges, but neither did he forget.”

As a young broadcaster, he added, “I was one of the people he took under his wing.”

Costas was among the many interviewees in “Glickman,” a 2013 documentary by Jim Freedman, who like Costas grew up in New York listening to Glickman’s football broadcasts.

At 17, Freedman worked as a producer on a radio show hosted by Glickman.

“It was the most exciting job I ever had,” he said.

Stoller, for his part, reportedly swore off running after the Berlin snub, but reversed course upon returning to the University of Michigan and was selected as a 1937 All-America. That year he also began acting and singing in films.

Apparently while on an athletic tour of the Philippines in 1938, he met his wife, Violet, a native of China, and the couple settled in his native Cincinnati.

Less is known about his life afterward. But Pat Vassilaros, a genealogy enthusiast who’d assisted “Seeking Kin” on a previous column, provided research that helped find the relatives of Stoller, who died at 69 in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., in 1985.

Working from U.S. Census data, Vassilaros learned that Stoller had two brothers, David and Daniel, and a sister, Tillie. Their mother, Sophia Katz Stoller, apparently died, and their father, Morris (also listed as Maurice), like Sophia an immigrant from Russia, married a woman named Martha, a Kentuckian. They had a son, Harry.

An obituary published upon Harry’s death in Cincinnati last September mentioned his survivors. One of his daughters, Kathy Kaplan, told “Seeking Kin” that Sam Stoller did not have any children.

To Bill Mallon, a past president of the International Society of Olympic Historians, the 2015 Berlin event, with Stoller and Glickman relatives attending, promises to be meaningful and poignant.

“For Jewish athletes to walk into the Berlin stadium, knowing what happened there in 1936, and what happened after – what Hitler did to the world, and especially to the Jews, in World War II; and then what happened in 1972 in Munich [when 11 Israeli Olympians were killed by Palestinian terrorists] – I’m not Jewish, but if you have a sense of history, that would be an odd and eerie feeling,” Mallon said.

Glickman lived to receive a 1998 award from the U.S. Olympic Committee as a way of atoning for 1936. The award was presented posthumously to Stoller.

Glickman’s death in January 2001, Nancy Glickman believes, spared him far greater grief: His grandson, Peter Alderman, 25, worked in the World Trade Center and was killed in the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 that year.

“It was a good thing, frankly,” she said of the timing of her father’s passing. “It would’ve devastated my dad.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at seekingkin@jta.org if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends. Please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.