Say “Vienna” and you think of café culture, fueled by Jewish wits like Karl Kraus, Peter Altenberg, Egon Friedell. Decadent, hothouse-rose painters like Schiele and Klimt. Strauss waltzes. Deft, mordant writers like Schnitzler and Stefan Zweig. Freud. Wittgenstein. Schoenberg.

Or you think of Karl Lueger, the father of “political” anti-Semitism. Or the streets lined with cheering Austrians when the Nazis marched into the capital in March 1938. Or Kurt Waldheim’s lapse of memory concerning his activities as a German officer.

Vienna is a city that has a rich, heavily Jewish-tinged cultural past, particularly in the years of the Emperor Franz Josef (who treated his Jewish subjects relatively fairly). Needless to say, filmmakers have been drawn to that period and its kitschier elements since the cinema was invented. The best of them — Max Ophuls, Billy Wilder, Ernst Lubitsch, Erich von Stroheim, Otto Preminger, Josef von Sternberg, all Jewish — managed to convey at once both the charms of the city with its coffeehouses and too-rich pastries, its giggling housemaids involved in assignations in the Prater, the arched eyebrows of its roués in uniform and its moral corruption that would eventually burst into full-blown genocidal fury when Hitler’s minions lit the fuse.

Ironically, Austria itself has a fairly slender film history prior to the post-WWII era. Her best filmmakers left for Berlin, Paris, London and, of course, Hollywood, some for glory and money, others to save their lives. But Vienna lingered in their memories and infiltrated their movies, as “Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema,” a new series at the Museum of Modern Art, amply testifies.

Timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Austrian Film Museum, an institution of incalculable importance for its efforts to preserve Central European film history, “Vienna Unveiled” is an unprecedented treasure-trove of great and important films, ranging from the long-lost silent gem “A City Without Jews,” adapted from Hugo Bettauer’s prescient 1922 novel about the forced deportation of Viennese Jewry, to contemporary films from Jem Cohen and Ruth Beckermann.

As you can see, the program focuses, quite rightly, on the Jewish presence in Central European film and culture. Sometimes the yiddishe tam comes from unexpected places, as in Stanley Kubrick’s valedictory “Eyes Wide Shut,” an adaptation of a Schnitzler novella. (Kubrick was Jewish, but you might be hard-put to prove it from his films themselves.) At other times, the flavor borders quite deliberately on the absurd, as in Wilder’s “The Emperor Waltz,” in which gramophone salesman Bing Crosby enchants the imperial court with his easygoing charm, and Wilder gently sends up his hero and role model, Ernst Lubitsch.

Regardless, the series includes 70 films, many of them quite rare and several of them masterpieces, and it is well worth a significant investment of time.

“Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema” runs Feb. 27 through April 20 at the Museum of Modern Art (11 W. 53rd St.). For information, call (212) 708-9400 or go to www.moma.org.

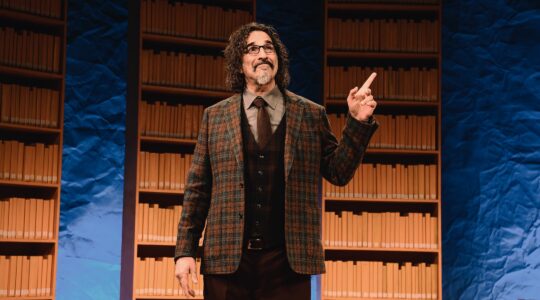

The Storyteller:

Simon Schama tackles Jewish istory.

Simon Schama loves stories — hearing them, reading them and telling them. As an historian, he has written several best-selling books on such subjects as the French Revolution and American slavery, that serve as reminders that in the hands of a master storyteller, history can be as compelling as any novel.

But there is one story that he had avoided telling, a story that is an integral part of his own identity.

“I wanted the histories I’ve written to be significant, not me,” he said in a telephone interview last week. “I have been pitching my historical flag in a culture not my own.”

Until now.

Schama’s latest book and television venture — these days, the two go hand-in-hand for him — is “The Story of the Jews,” a five-part BBC-produced series that will be published in book form in March, and air on PBS later the same month.

He just couldn’t escape the strong gravitational pull of the Jewish story. As a project it has been following him around for over 40 years, since he was asked to finish Cecil Roth’s majestic history of the Jewish people after Roth’s death.

“It has always been lurking there, a scary sort of thing,” Schama said, laughing. “The passion and the subjectivity of it [frightened me], and I suppressed it. I told them I just couldn’t do it, but it wouldn’t go away, it kept tugging at my sleeve.”

When the BBC came calling recently, he recalled, “I had to have a crack at it.”

The result is a five-hour meditation on the ups and downs of the Jewish people over 5,000 years, as seen through a series of narratives of great dramatic appeal.

Schama said, “My father’s family called themselves ‘Sephardic trash.’ The family story is that my great-great-grandparents were spice sellers in Izmir. My mother’s family were Litvaks, from Kovno-Gobernya, and they were in lumber like so many Jews in that part of the world, schlepping timber across the fields. But my parents were both first-generation British born.”

One thing that united these disparate clans was “the habit of storytelling,” the historian recounted. And that, he said, is what he brings to a topic that has been essayed many times before.

“Storytelling and new scholarship, that’s what I bring to the subject,” he declared. “On one level, I’m just a ventriloquist for scholars who have been doing new research. I wanted to write a Jewish history that was narrative. I didn’t want to do a chain of texts and philosophies; I’m not good at that. What I can do is introduce readers and viewers to the Jews of Elephantine [a 5th-century B.C.E. island military outpost in the middle of the Nile] and David of Oxford [a contemporary of Richard the Lionhearted].”

He concluded, “I think that’s worth doing. The [Jewish] story is so inspiring and rich and digressive and surprising. When when I was asked I thought, ‘Why not?’”

“The Story of the Jews,” written and hosted by Simon Schama, will be broadcast March 25, 8-10 p.m. (episodes 1 and 2) and April 1, 8-11 p.m. (episodes 3, 4 and 5) on PBS. Check local listings for details. “The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words, 1000 B.C – 1492 A.D.,” the first of two volumes by Schama, will be published in March by Ecco Press.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.